UDC: 327(497.11:450:496.5)“1912/1914“

DOI: 10.34298/9788677431402.12

Biljana STOJIĆ

Institute of History

Belgrade

Serbia

Abstract: This paper examines Serbia’s goal to provide an outlet to the Adriatic Sea in the First Balkan War and the consequences of that attempt until the outbreak of the Great War. “The War for the Sea” was a brief episode from 1912, but important and very indicative for the later course of events and Italo-Serbian relations. Serbia’s aspiration towards the Albanian coast was not due to an imperialistic ambition, as was claimed by the Austro-Hungarian propaganda, but rather a way out from the Habsburg Empire’s strong economic and political pressure on Serbia. But in this peculiar endeavor of November–December 1912, Serbia’s desire conflicted with the interests of Italy. Being a great power, Italy cherished its interests in Albania long time before and after 1912. The discussed topic will be presented in the chronological order from Serbia’s perspective and its relations with Italy and Austria-Hungary. A focus is also placed on the origin of the idea, the ongoing war operations until the London Peace Conference (December 1912 – May 1913) and finally through the work of two international border demarcation commissions (October 1913 – June 1914). The facts presented in the paper rely on documents kept in Serbian and foreign archives, as well as on relevant literature.

Keywords: Serbia, Milovan Milovanović, Italy, AustriaHungary, Albania, Adriatic Sea, First Balkan War, Great War, diplomacy.

The coup d’état that took place in Serbia in 1903 did not only bring back to the Serbian throne the Karađorđević dynasty, but also motivated the political elite to start a decisive struggle against Austria-Hungary’s economic and political pressure.However, as the Danube Monarchy was building its supremacy over Serbia for over two decades, it was not willing to give up easily on all the gained prerogatives. In order to keep its influence, Austria-Hungary undertook two pressure attacks on Serbia– one struck the economy and the other was political. First came the economic pressure. When in 1904 it learned that Italy was encouraging Serbia and Bulgaria to conclude an anti-Austrian agreement, the Austro-Hungarian propaganda used all means to undermine that deal. Vienna acted against the agreement despite the fact it was honouring the status quo in the Balkans and the Mürzsteg Reform Programme (1903). From Vienna’s point of view, the troubling points were an announcement of a customs union between Serbia and Bulgaria, as well as Bulgaria’s promise to support Serbia’s aspiration in the direction of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. For Austria, the appearance of another trading market for Serbian products was unacceptable. Likewise, with the approval of the great powers at the Congress of Berlin (1878), Austria still had three military posts in Pljevlja, Priboj and Prijepolje, and the Serbo-Bulgarian agreement implied that Serbia’s goals directly clashed with Austria’s in that region.1

By pressuring both sides, Austria easily managed to annul the concluded agreement. Nonetheless, it used the agreement and the armament crisis in Serbia as a pretext to start the customs war. Refusing to extend contracts and closing borders for Serbia’s agricultural goods and livestock, Austria expected to quickly bring Serbia to its knees and anticipated that Serbia’s economy would not survive the attack. It was, however, wrong. Entering in this unequal duel, Serbia was aware that it had to endure until the end and to radically cut off all remaining strings with Austria.2 The Serbian economy did not only endure six years (1906–1911) in this war known as the Pigs’ War, but also came out from it significantly stronger. Serbian policymakers managed to conclude contracts with other European countries (Germany, France, Belgium, the Ottoman Empire, etc.) and to redirect products to other markets.3

The Austrian second pressure attack that came in 1908 was political and, as such, more intense. Austria made the decision to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina as a gift for the 60th anniversary of Franz Joseph’s reign. For such act Count Gołuchowski got the consent of Russia but not of other great powers. As Bosnia was considered Austria-Hungary’s main strategic aim, the country’s annexation instantly sparked a tense crisis in Serbia. Given that the annexation violated the Berlin Treaty, Milovan Milovanović, Serbian Prime Minister, raised the crisis from the local to the international level, with the intention to gain compensations for Serbia. Although Iswolsky gave the green light to his Austrian colleague, when the crisis broke out, he stood by Serbia’s side. Even so, Russia did not contribute much to resolving the crisis since it was still recovering from the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the Revolution from 1905. On the contrary, Russia’s taking Serbia’s side provoked Germany to step forward from the shadow and firmly support its ally, Austria. The Annexation Crisis lasted for five months (March 1909) and ended with Serbia and Russia’s diplomatic defeat and, on the other hand, the strengthening of the Austro-German position in the Balkans.4

Even the painful experience such as the Annexation Crisis was a valuable lesson to all sides. From Serbia’s point of view, the biggest success was Milovanović’s manoeuvre to incorporate the country’s interests into those of Russia and France. Milovanović described this policy as “hooking up a small Serbian boat to the great Triple Entente’s ship”. While the crisis lasted, he also learned that having Russia’s support was not sufficient in the constellation of foreign affairs. Serbia had to rely on more than one great power. In that matter, France and Great Britain were considered friendly powers because of their alliance (1892/3) and the friendship agreement (1907) with Russia. It is true that the Franco-Russian alliance was contentious during the Annexation Crisis, but soon after both countries came to the mutual standpoint that they had to stand together more firmly. By 1912 they overcame all disagreements, established a close alliance and created complementary politics in every segment, including a mutual opposition against the Central Powers’ breakthrough to the East. Using the change in the French foreign policy, Milovanović managed to persuade French financiers to help Serbia recover from the crisis with the loan of 150 million dinars, granted in autumn 1909. Financiers approved the loan in the spirit of the new French foreign policy –“building a dam in the Balkans against German imperialism“.5

The origin of the idea of an outlet to the sea

After 1909 and the Annexation Crisis, even Great Britain, traditionally the least interested in Balkan affairs, started to show sympathy with Serbia’s unfortunate fate.6 Describing the complexity of Serbia’s position towards Austria-Hungary, British journalist James Louis Garvin stated in 1909: “Serbia is a surrounded country, and

Serbs are people under arrest“. Quoting Garvin, Jovan Cvijić underlined the necessity and legitimacy for Serbia to request an outlet to the sea, because any further progress of the country would be impossible.7

Prime Minister Milovanović concluded the same. Seeking the way out from the Austro-Hungarian encircling, he came to the idea that the only way to assure Serbia’s

political and economic survival was to get an outlet to the Adriatic Sea. He strongly believed that the only possible outlet to the sea was in northern Albania. At first, this

idea caused a great shock among Serbian politicians. Defending this daring idea, Milovanović called upon Serbian scholars who claimed that northern Albania and Old Serbia were geographically and ethnographically the same, compact region.8 Therefore it would be most natural for Serbia to assimilate the northern part of Albania as France did with Bretagne.9 Besides this argument, Milovanović also pointed out an old Serbian plan for the construction of an international railway aiming to link the Adriatic Sea and the Danube.10 He argued that Serbia’s harbour on the Adriatic Sea would serve for commercial purposes and would benefit not only Serbia, but also all

other countries with interests in Albania, Austria and Italy in particular. In February 1908, before the Annexation Crisis, the railway project had the support of Russia,

Italy and a multinational company with English, French and Italian capital. From the start, Italy seemed to be the most interested in this project, as it could provide the

shortest way to the very heart of the Balkan Peninsula. For that matter, Italian diplomats took on themselves to convince Vienna and Constantinople to approve and support the railway project.11

Milovanović tightly linked the outlet idea with another daring plan – the alliance of the Balkan Slavs gathered around the same cause. At first sight, these two ideas had

nothing in common, but from Milovanović’s point of view they were inseparably connected. The experience of the Annexation Crisis taught him that in the struggle for

political and economic independence from the influence of the great powers, small Balkan states did not have any chance if fighting alone. Painfully, Milovanović learned

that the great powers always had and would have their own agendas and would always be achieving their objectives at the expense of smaller countries. Consequently, he knew that if Serbia started alone the struggle for the outlet in Albania, still part of the Ottoman Empire, where Austria and Italy exerted much influence, it would confront all three powers and experience a failure.12 Only united, small Balkan states could ensure their economic welfare and political stability. Therefore, since 1909, Milovanović became literally obsessed with the idea of the unification of the Balkan states within one or more alliance(s). For such agenda he had a green light from Russia. Humiliated in the Annexation Crisis, Russia was seeking a way to settle the score with Vienna and to regain its strategic position in the Balkans. Despite a strong will, after the war with Japan, the Revolution and the Annexation Crisis, Russia was weak and wanted to avoid a direct confrontation with Austria. The opportunity to take revenge disguised in an anti-Austrian Balkan alliance served as a perfect pretext for Russia, which gladly accepted the idea to be the Alliance’s patron. Accordingly, the new Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Sazonov sent new ambassadors to the Balkans: Nikolay Hartwig (1909) in Belgrade and Anatoly Nekludov (1911) in Sofia, with the task to assist in the rapprochement of Serbia and Bulgaria, the two biggest and most important states, as a sustainable alliance between them could be the basis for any further planning.13

Bulgaria was the biggest and militarily the strongest state, so it was clear that without it, any Balkan union would be ineffective. Serbia and Bulgaria already shared the experience of two unsuccessful alliances. Before the alliance from 1904, there was the one concluded in 1897. This alliance failed because neither side showed the willingness to apply it in practice.14 In order to avoid the third failure, Milovanović decided to negotiate with Bulgarian politicians secretly and in person. Eager to conclude an alliance with Sofia, Milovanović was even ready to renounce Serbia’s claims in Macedonia. Instead towards Macedonia, Milovanović decided to focus Serbia’s aspiration in the direction of northern Albania. By doing so, he managed to link both strategic goals: an outlet to the sea and the Balkan League. It is important to stress out that renouncing Serbia’s ambitions in Macedonia was the only way to reach an agreement with Bulgaria, and Milovanović believed that a sustainable alliance with Sofia was more important for the future than a bigger share in Macedonia.15

Nikola Pašić and the majority of the Serbian elite disagreed with Milovanović’s plan. Pašić repeated in vain that Macedonia was “the most important point in the entire Balkan Peninsula and those who have it hold the keys of the strongest influence in the entire Balkans”. He warned Milovanović not to deliver willingly those “keys” to Bulgaria and Greece, but Milovanović was determined to pursue the plan and endured with the backing of Nikolay Hartwig.16

The negotiations between Belgrade and Sofia started in 1910 and, with a few interruptions, lasted until spring 1912. The treaty was finally signed on 13 March. On that occasion, Milovanović solemnly declared that it was “the most important day for Serbia and Bulgaria, but also the greatest day for the entire Balkan Peninsula”.17 The Serbо-Bulgarian treaty served as the basis of the Balkan League. Greece and Montenegro joined the alliance with their deals. The peculiar fact regarding the Balkan League was that the four countries were not joined under a single mutual treaty, but through many unilateral treaties: Serbia with Bulgaria, Bulgaria with Greece, Serbia with Greece, Serbia with Montenegro. Greece did not have any treaty with Montenegro, while Bulgaria concluded only a verbal agreement with Montenegro. From that point of view, it is historically more accurate to speak about Balkan allies instead of an alliance or league. But we are referring to them as a unity because all agreements were concluded simultaneously during spring–autumn 1912 and all four states gathered around the same idea – to put an end to the authority of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans for good. Consequently, the great powers referred to the Balkan League as an additional, “seventh great power”.18

Unfortunately, the main designer of the League Milovanović did not live long enough to see the accomplishment of his lifework. He died suddenly, on 18 June 1912.

Pašić took power in September and found himself in a challenging situation as he was to continue Milovanović’s plan, which he opposed. At first, Bulgaria feared that Pašić would cancel the agreement, but it was too late for any changes as all four countries were completing war preparations. With the support of Russia’s and Serbia’s public opinion, Pašić agreed to follow the path already opened by Milovanović.

From an idea to reality: the war for the sea

As previously agreed among the allies, Montenegro started hostilities the first, on 8 October.19 Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece followed ten days later.20 The Serbian army

went into three directions: towards Macedonia, the Kosovo valley and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar.21 The third Serbian army operated in the direction of the Adriatic Sea and

already on 3 November it liberated entire Kosovo and Metohija and reached Prizen. Commenting on this news, Austrian newspapers wrote that “with the fall of Prizren,

Serbia should end its warfare” and “there is no ethnic or military justification for Serbia to go further than Prizren“.22 Despite all these serious warnings, the Chief of Staff of the Serbian Army ordered two battalions to continue marching towards the Adriatic Sea. However, the battalion’s commanders were instructed to march secretly. Serbia was hoping that if the army behind Austria’s back quickly took control over San Giovanni di Medua and Durres, Austria would not have any choice but to accept

fait accompli. While two battalions were marching towards the Adriatic coast, Serbia’s diplomacy started its own battle to persuade other great powers to grant it the access to the sea with the justification that without it Serbia could not be considered an entirely independent country.23

As the League’s patron, Russia knew and approved Serbia’s ambition for an outlet on the Adriatic coast. Despite this support, Sazonov and the Tsar did not want a large scale confrontation with Austria and therefore aimed to avoid another annexation crisis. Tied through an alliance with Russia, France knew about the treaties concluded among Balkan states since August 1912, when Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré visited St Petersburg.24 Poincaré advocated the opening of the Eastern Question, but

out of respect for his ally, did not oppose the idea that Serbia had an access to the Adriatic Sea. He and his closest associate Maurice Paléologue believed it was better for France to deal with a small state such as Serbia instead of letting Austria or Italy increase their influence in the Mediterranean. However, despite a possible leverage

that the Serbian presence in Albania could bring to France, Poincaré was not ready to enter into an open confrontation with the Triple Alliance over a local question in the

Balkans. Great Britain was even stricter. Lord Edward Grey thought that Russia was the most responsible for the outbreak of the Balkan War and therefore it was the

duty of Russian diplomacy to settle all issues. Grey kept a neutral position out of courtesy for France and Russia, but as France, Britain did not want to be dragged into

a war in the Balkan Peninsula.25

While the Triple Entente was reserved, the Triple Alliance demonstrated unquestionable concord in this and all other issues. At least that was the impression from the perspective of the opposite bloc. Beneath the alliance’s surface there was a lot of animosity in Vienna–Rome relations, and Germany was forced to act among them as a mediator. Those animosities were not new or upraised with the Balkan War. Italy joined Austria and Germany’s alliance in 1882 to get a free hand in spreading the influence in northern Africa, where it confronted France and Great Britain. For the time being, Rome needed a counterbalance, but underneath there was huge hostility towards Austria as Trentino and Trieste were within Austrian borders.26

Aiming to adopt a joint stance towards Serbia’s outlet, Germany initiated negotiations of the Triple Alliance in Berlin in early November. The main purpose of the meeting was to smooth out the increasing differences between Austria and Italy. At the meeting, Italy was represented by Marquis Antonio di San Giuliano. After coming back to Rome, San Giuliano gave his version of the discussions to French ambassador Camille Barrère. He said that Count Leopold von Berchtold, the Austrian Minister of Foreign Affairs, was furious that Serbia even dared to send its army in the direction of the Adriatic Sea and requested full support of Germany and Italy to punish Serbia.27 The Austrian Foreign Ministry stressed that the territory inhabited by the Albanian people should be organized in one independent Albanian state and ruled by a Muslim prince. Furthermore, Berchtold emphasized that Austria would not change this stance regardless of the pressure of other powers, and that Vienna would impose severe measures against Serbia with or without the support of its allies. San Giuliano said to Barrère that before that meeting he did not have a clear standpoint regarding the Serbian outlet, but Berchtold’s robust reaction forced him to step forward and stand by his ally. San Giuliano made it very clear to Barrère that Austria was even ready to start a war in order to prevent Serbia in its aim. He also admitted that he personally would have rather supported than opposed Serbia’s goal, since, just like as for France, for Italy it was better to deal with a small Balkan state instead of clashing with Austria over influence. Once more, he stressed that Italy had many conflicting interests with Austria in Albania and elsewhere, but the current situation did not allow Italy to have an open dispute within the Alliance. Italy was still weak after the war against the Ottoman Empire, which had just ended with the Treaty of Lausanne signed on 18 October 1912 under the pressure of other great powers. San Guiliano’s standpoint from Berlin was supported by the President of Government Giovanni Giolitti, who even argued that “it is not Italy’s role to fight for Serbia’s and the Balkan cause more vigorously than, for example, Russia”.28

The adopted attitude of the Triple Alliance was delivered on 10 November to the Serbian Government through a démarche handed over by the Austrian Ambassador in Belgrade, Stephan von Ugron. The character of the démarche was threatening. Even so, Pašić decided not to rash any decision, but instead chose to ignore the démarche and leave Belgrade for a couple of days. Despite the seriousness, he was placing all hopes in Russia’s hands and therefore told the Serbian Army General Staff to continue the operation in Albania. However, with the involvement of two other members of the Triple Alliance, the crisis deepened and, as such, put Russia in an extremely dangerous position. Russian diplomacy was unprepared to confront Austria-Hungary, supported by Germany and Italy. Also, the Russian Government knew that it could not count on reciprocal support of its allies. Both France and Great Britain were very clear that they did not want to be involved more than it was necessary in the question such as the Serbian outlet to the sea. France had more patience and understood Russia’s position and the pressure it suffered, and Poincaré discreetly stated to Sazonov that it would be very difficult for him to explain to his fellow Frenchmen why they need marching for a Balkan problem and not for Lorraine and Alsace. This was the French attitude from the Annexation Crisis, but the difference was that, just like Clemenceau in 1909, Poincaré did not plan to abandon Russia entirely. He was reserved but offered all diplomatic tools to resolve this and all other open issues.

Sazonov appreciated the friendly attitude of his French colleague and for that reason the Russian final decision regarding the Serbian request was first presented to France. On 12 November, Russian Ambassador Alexander Iswolsky declared that Russia would continue backing Serbia with all diplomatic means, but refused to be dragged into the war because of Serbia’s Adriatic port. Poincaré cordially congratulated his Russian colleague on the rational and only possible decision in the current situation.29 On the same day, the Russian standpoint was presented to the Serbian Government. Unlike France, Serbia was deeply disappointed and felt betrayed. Hartwig, the Russian representative in Belgrade, explained to Pašić that the Adriatic issue was extremely dangerous, and therefore advised him to declare that Serbia would accept any mutual decision of the great powers which would be adopted at a peace conference. Hartwig reassured Pašić that Russia would continue to do everything in its power to negotiate the best possible solution for Serbia. Following Hartwig’s advice, Pašić announced on 16 November that Serbia would honour any decision of the great powers.30 This was a declaration for Russia and the European public, while, in fact, Pašić personally still believed that there was some room left for

a diplomatic manoeuvre. As the last resort, he placed his trust in support of Russian Slavophil circles. Believing in their capacity, Pašić refused to order the Serbian army

to quit marching and to withdraw from Albania. On 18 November, two battalions reached the sea, entered Alessio (Lješ), but did not stop there and continued further

in the direction of Durres and Valona.31

Pašić’s behaviour was due to another important factor. He and the Serbian Government were aware that Austria secretly organised a mission of 15 Albanian leaders, led by Ismail Kemal-bey. The goal of this mission, which started its journey from Constantinople on 6 November, was to reach Albania and proclaim independence before the Serbian army seized Alessio, Durres and Valona. Although it began its journey only three days after the Serbian army started marching towards the sea, the Albanian delegation was behind because it lost much time lobbying along the way: Budapest, Vienna and Trieste. In Trieste, on 20 November, the mission attended the Pan-Albanian Congress, organized with the support of the Albanian emigration in Italy and Austria.32 While Ismail Kemal was securing support around Europe, the Serbian army advanced in its endeavour. The unexpectedly fast progress of the Serbian army forced the Albanian mission to leave Italy in a hurry and speed up towards Valona. With the help of Austria and the Albanian emigration, Ismail Kemal called an assembly for 28 November. A peculiar fact was that he and the rest of the delegation did not speak Albanian and held the assembly in Turkish. At the end of their address, the people shouted independence. Only one day later, the Serbian army entered Durres, the final destination of their journey. From the military point of view, this was the last and most significant victory in the First Balkan War, but diplomatically, that victory brought Serbia to a stalemate, i.e. under the threat to be attacked by AustriaHungary.33

Revolving the crisis and its consequences

The moment when the Serbian army entered Durres was the highlight of the crisis. Emperor Franz Joseph, Count Berthold and leader of the Military Party Conrad von

Hötzendorf were infuriated and ready to send the army over the borders at any moment. Although angry, Austrian policymakers were not ready to act alone without Germany’s backing at least. Thankfully, the worst scenario was avoided thanks to the fact that Germany was not ready for a largescale war in 1912. As regards the

opposing bloc, the French Prime Minister, later President Raymond Poincaré, with his diplomatic moves, gave a great contribution to resolving the crisis. He managed

to persuade other powers to accept his idea of the peace conference. Poincaré’s suggestion regarding the peace conference was on the table from the first day of the

war, but belligerent countries and great powers rejected it as premature. During the lobbying, Poincaré was forced to accept some modification of his proposal; the most significant was the change of the venue. Instead of Paris, Germany insisted that the meeting be moved to London as a neutral place for all sides. Poincaré did not want

to tighten already fragile relations between Paris and Berlin and agreed with this change at end of November.34

In the weeks that preceded the London Conference, Serbia tried once again to gain the backing of friendly powers, and for such mission it engaged the most prominent Serbian intellectuals. Historians, linguists, geographers, anthropologists were busy with publishing articles and brochures aiming to support Serbia’s request for an outlet. However, at the end, all their efforts were insufficient. Austria listed the Albanian question as the first and most important on the Conference agenda. It was scheduled to be discussed on the first Conference day, 17 December.35 After introductory speeches, Ambassadors, as the representatives of the six great powers, adopted the following formula: “Serbia will get a commercial outlet through one free and neutral Albanian port, to which it will be connected with the international railway under European control and the protection of special international forces. Serbia will have the liberty of transit of all goods, including military munitions”. This formula was

followed with another one concerning Albania’s status: “All six powers will be guarantors of Albanian autonomy, but the principality will remain under the sovereignty of the Sultan”.36 Such opening of the Conference was a bitter disappointment for Serbia. At the moment when the decision was issued, the Serbian army was still in Albania, keeping positions and hoping for a miracle. But all hopes were dashed when the Ambassadors accepted the formula “of a commercial outlet”, which cut off for good Serbia’s passage to the sea. Both formulas underwent many changes during the months of negotiations. At the end, the formula regarding Serbia’s commercial outlet turned into an empty promise on paper without the intention to ever be applied in practice, while Albania’s provisional attachment to the Ottoman Empire was intersected completely. Consequently, Albania turned into an independent principality, whose autonomy was monitored by the great powers. Ambassadors’ attention in the following months was refocused on the crisis concerning Scutari, Edirne and Yanina, while the outlet crisis was considered closed. From the great powers’ point of view, what was left to be resolved were border demarcation and state organisation.

Albania’s interior organisation and demarcation of borders brought to the surface the Austro-Italian treaty concluded by Visconti Venosta and Count Gołuchowski in 1896. The agreement was ratified by both sides in 1900/1. Interpreting this deal, European diplomats argued that it provided more protection for Italy. By signing this agreement, Italy did not care for the wellbeing of the Albanian people and did not aim to pursue a competitive policy with Austria. However, as a weaker side, Italy wanted

to protect its rights in Albania. Using the treaty as an excuse, Italy spread its propaganda in Albania through the school system, church, public infrastructure, political and financial support to local leaders. Italy reserved for itself the influence in the coastal region, while Austria was building its network the inner part of the country. The moment of Albanian independency implied a new level of influence for both states and opened a new arena for confronting interests. The first issue where their interests clashed was the election of the future Albanian ruler. The struggle for such role began soon after Albania proclaimed independence in December 1912. Some candidates presented their candidacy by themselves as it was the case with Egyptian prince Ahmed Fuad Pacha or Rоmanian Prince Albert Constantine Ghica, but they were nominated mostly by Rome or Vienna.37 The two most serious candidates were Prince Wilhelm of Urach, Count of Württemberg and Duke of Urach, as the Austro-Hungarian candidate, and Captain Wilhelm of Wied as the Italian candidate. Italy succeeded to discredit the Duke of Urach in favour of Captain Wied, a Protestant prince and the son-in-law of the King of Württemberg. Since Prince Wied was poor, Italy anticipated that it would easily manipulate him. Furthermore, as a Protestant, he was expected not to give advantages to any of the three dominant religions in Albania. Captain Wied declined the Albanian throne two times, but after promised to receive

ten million francs he accepted the candidacy in autumn 1913.38 That moment was considered a big diplomatic success for Italy.39

All work concerning Albania was very exhausting for France, Russia, Germany and Great Britain because Italy and Austria-Hungary used every situation to sabotage any solid deal. At the London Conference, Paul Cambon, the French ambassador, described his Italian colleague Marquis Guglielmo Imperiali as the one who spoke the most but, at the end, always voted in accordance with Germany and Austria. Italy and Austria were justifying their imposing themselves in every situation with the argument that they were the powers most interested in all Albanian issues and therefore the most entitled to decisionmaking. Other powers argued in vain their “preeminence”, and, in fact, the Ambassadors adopted the majority of measures aiming to deprive them of full liberty of pursuing their influence in Albania.

The issue concerning the drawing of Albania’s borders turned out as overly complex, not only because of Austro-Italian obstructions. At the first Conference meeting, Austria insisted that Albania’s border with Montenegro be in the north and with Greece in the south, thus dashing even the slightest Serbia’s hope of getting a

commercial outlet. At the meeting held on 10 April 1913, the Ambassadors sketched the definitive borders of Albania. Montenegro, which endured the Siege of Scutari,

was very dissatisfied with the demarcation. Serbia and Greece were dissatisfied as well, and submitted to the Ambassadors dozens of complaints regarding the proposed borders. Italy also had many objections; it was preoccupied mainly with the coastline and islands in the Ionian Sea. Italy requested that Corfu and its canal remained neutralized for a strategic reason. Marquis Imperiali asked the same for all islands in the Eastern Mediterranean which were held by Italy from the Cyrenaica War (1911–1912). Despite all pressure from Italy, the Ambassadors reached the decision that Italy was obliged to turn over all islands to Greece, that Corfu would be a part of Greece, while the Corfu canal would remain neutral. It was a small satisfaction for Italy’s entire diplomatic endeavour.40

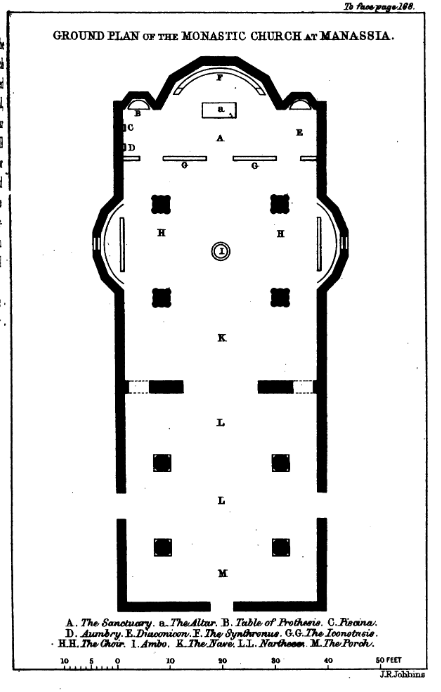

In order to get more precise and accurate borderlines, the Ambassadors decided to organize two commissions consisting of six delegates (one per each great power), with the task to settle the demarcation lines on the ground. Commissions had a technical mandate, i.e. were to put in practice the Ambassadors’ decisions. One commission was in charge of the borders in the north and east, i.e. with Serbia and Montenegro, while the second was in charge of the southern border – with Greece.

Because of the open crisis concerning Scutari and the Second Balkan War, commissions were unable to start their work in September as it was planned. Another

issue was that Austria and Italy procrastinated with the nomination of their delegates until late summer 1913.

After the troubling issues were resolved, the first commission started to work on 20 September from Ohrid. The second commission started from Bitola a month later,

on 24 October. The Italian delegate for the commission in charge of the northern and eastern borders was Colonel Marafini, and the Italian delegate for the Albanian-Greek commission was consul from Skopje Labia. As for Austria-Hungary, Colonel Mitzl defended Austrian interests in the commission in charge of the northeastern border, and consul Bilinski was designated for the southern border.41 Both commissions faced many problems. The delegates were in constant mutual quarrels and their work was slowed down by the impassable terrain and frequent interruptions. The first phase was concluded with the Florence Protocol signed on 17 December 1913. Until that date, the commission for the northeastern border demarcated only 85 km of the border, and the second commission even less. The plan was that the two commissions continue their work in spring 1914, i.e. late April. The second phase of the commissions’ work was very similar to the previous period. The Sarajevo assassination on 28 June 1914 permanently interrupted the work of delegates. For security reasons, all delegates left Albania in early July 1914.42 The commissions’ unfinished job placed the entire Balkans in an extremely difficult position during the First World War. Albania’s borders remained unresolved in all directions, which is why the neighbouring countries were exposed to many invasions of Kachaks. An additional problem was that since he lived for a short time in his new homeland, Prince Wied did not establish any ruling system; therefore, after he fled the country, the anarchy among the tribes reached the highest level. In October 1914, aiming to protect the Greek minority, Greece enforced its control over the northern Albanian part of Epirus. Italy followed the Greek example and took control over Valona and the entire coastal

zone. Preoccupied with the warfare in the north, Serbia suffered the most of Kachak invasions. This particular problem did not emerge with the war as it was present long

before the Balkan Wars. Serbia tried on multiple occasions to bring this problem to the attention of the great powers and even intervened militarily in autumn 1913, and

then again in 1914 and in 1915. The only thing Serbia achieved by sending its army to Albania was that Russia and France told it to focus all its strength towards the

northern front, instead of losing energy in the south.

The unfortunate turnaround in autumn 1915 brought back the Serbian army once again to Albania. However, those were no longer the victorious troops from 1912, but famished and exhausted soldiers escaping from the Austro-German-Bulgarian troops. On the Albanian coast, the decimated Serbian army was met by the Italian allies. Remembering Serbia’s territorial pretensions three years before, Italy suspected that Serbia had a similar agenda despite the circumstances, and strongly opposed Serbian troops staying and getting reorganised in Albania. It considered Albania its exclusive zone of influence and did not want any other state/army in a close range. It therefore gave the majority of ships for the transport of the Serbian army to Corfu. Despite many interventions of Russia, France and Britain, and the transfer of the Serbian army to the Thessaloniki front in April–May 1916, throughout the war Italy remained highly suspicious towards Serbia and its war goals which would again clash with the Italian goals in Dalmatia and Istria in 1918.

Biljana Stojić

DIMENSIONE INTERNAZIONALE DI UN PROBLEMA LOCALE: GLI OBIETTIVI DELLA

SERBIA CONTRO LE PRETESE ITALIANE IN ALBANIA (1912-1914)

In questo articolo abbiamo discusso il tentativo della Serbia di assicurare a se stessa l’accesso al mare Adriatico attraverso un porto sulla costa albanese. Sebbene l’impresa risalga al 1912 durante la prima guerra balcanica, la stessa ebbe conseguenze di vasta portata per le relazioni internazionali anche durante la Prima guerra mondiale. L’ideatore ideologico del piano serbo di arrivare al mare attraverso l’Albania fu il Primo Ministro Milovan Milovanović, che iniziò a considerare questa idea dopo la crisi dell’annessione. Per un piano così audace, Milovanović si assicurò il sostegno della Russia e la neutralità degli Stati amici di Francia e Gran Bretagna. Milovanovic riuscì a far passare l’idea di arrivare al mare incorporandola nel progetto di un’alleanza di Stati balcanici e impostandola come obiettivo principale della guerra dell’esercito serbo nella prima guerra balcanica (ottobre 1912 maggio 1913). Tuttavia, la campagna serba in mare non solo interferì nelle relazioni con l’Impero Ottomano, ma mise anche la Serbia di fronte agli interessi di due grandi potenze: l’Italia e l’Austria-Ungheria che erano vincolate da un accordo di divisione di sfere di interesse e da un accordo per risolvere congiuntamente tutte le questioni relative all’Albania.

Nonostante l’accordo, le relazioni austroitaliane erano contraddittorie, e questo fu particolarmente evidente in questo caso. Gli eventi dal novembre 1912 al luglio 1914 sono presentati cronologicamente, visti attraverso il prisma delle relazioni austro-italiane e serbe verso queste forze, sono analizzati gli interessi comuni e opposti dei due blocchi di grandi potenze, i lavori della Conferenza degli ambasciatori a Londra, la scelta del sovrano albanese, la demarcazione dei confini dell’Albania nonché le conseguenze della marcia serba verso il mare che riguardano i rapporti tra Serbia e Italia durante la Grande Guerra. Il lavoro è stato redatto sulla base di documenti d’archivio conservati in archivi nazionali ed esteri, nonché sulla base di rilevanti opere storiografiche.

Parole chiave: Serbia, Milovan Milovanović, Italia, AustriaUngheria, Mare Adriatico, Prima guerra balcanica, Grande Guerra, diplomazia.

Биљана Стојић

МЕЂУНАРОДНА ДИМЕНЗИЈА ЛОКАЛНОГ ПРОБЛЕМА: ЦИЉЕВИ СРБИЈЕ

НАСУПРОТ ИТАЛИЈАНСКИМ ПРЕТЕНЗИЈАМА У АЛБАНИЈИ (1912–1914)

Резиме

У раду смо разматрали покушај Србије да себи обезбеди излаз на Јадранско море преко једне луке на албанској обали. Премда је подухват датиран у 1912.

годину у време Првог балканског рата, имао је далекосежне последице по међународне односе и у Првом светском рату. Идејни творац плана изласка Србије на море преко Албаније био је српски премијер Милован Миловановић који је ту идеју почео да разрађује после Анексионе кризе. За такав смео наум

Миловановић је обезбедио подршку Русије и неутралност пријатељских држава Француске и Велике Британије. Миловановићу је пошло за руком да идеју

изласка на море инкорпорира у идеју стварања савеза балканских држава и постави је за главни ратни циљ српске војске у Првом балканском рату (октобар 1912 – мај 1913). Међутим, српски поход на море није задирао само у односе са Османским царством већ је Србију конфронтирао интересима две велике силе – Италије и Аустроугарске. Њих је везивао уговор о подели интересних сфера и договор да ће заједнички решавати сва питања у вези са Албанијом. Упркос договору аустро-италијански односи су били контрадикторни што се особито видело у овом случају. Догађаји од новембра 1912. до јула 1914. године хронолошки су изложени, посматрани кроз призму аустроиталијанских и односа Србије према овим силама, разматрани су заједнички и супростављен интереси два блока великих сила, рад Амбасадорске конференције у Лондону, избор албанског суверена, одређивања граница Албаније и на крају последице српског марша на море по односе Србије и Италије током Великог рата. Рад је написан на основу архивских докумената похрањених у домаћим и страним архивима, као и на основу релевантних историографских радова.

Кључне речи: Србија, Милован Миловановић, Италија, Аустроугарска, Јадранско море, Први балкански рат, Велики рат, дипломатија.

- I. Kosančić, Novo‐pazarski sandžak i njegov etnički problem, Beograd 1912, 1; M. Dašić, Administrativno‐teritorijalni položaj Stare Raške u doba turske vladavine i nastanak imena Sandžak, Oblasti Stare Raške krajem XIX i početkom XX veka, ur. P. Vlahović, S. Gojković, Prijepolje 1994, 13‒37; M. Jagodić, Srpsko‐albanski odnosi u Kosovskom vilajetu (1878‒1912), Beograd 2009, 4‒15; S. Terzić, Stara Srbija (19‒20. vek): drama jedne civilizacije, Novi Sad‒Beograd 2012, 34‒44. ↩︎

- According to Dimitrije Đorđević, the French loan from 1906 was important for two reasons: first, it implied Serbia’s victory in the customs war and, secondly, it opened the door to the French influence in politics and the economy. From 1906 France started to build its own supremacy in the Balkans, which came to the fore in the interwar period (D. Đorđević, Carinski rat Austro‐Ugarske i Srbije 1906–1911, Beograd 1962, 215; B. Stojić, Francuska i balkanski ratovi (1912–1913), Beograd 2017, 40–66). ↩︎

- V. G. Pavlovic, De la Serbie vers la Yougoslavie. La France et la naissance de la Yougoslavie 1878–1918, Belgrade 2018, 99. ↩︎

- M. Nintchitch, La crise bosniaque (1908‒1909) et les puissances européennes, I, Paris 1937; P. B. Miller, From Annexation to Assassination. The Sarajevo Murders, 1908: l’annexion de la BosnieHerzégovine, cent ans après, dir. C. Horel, Bruxelles 2011, 239–253; S. Jovanović, Milovan Milovanović (II), Srpski književni glasnik (SKG) 51, 3 (1937) 172‒180; D. Đorđević, Milovan Milovanović, Beograd 1962, 126. ↩︎

- D. Boarov, Apostoli srpskih finansija, Beograd 1997, 133; S. Skoko, Vojvoda Radomir Putnik, II, Beograd 1984, 18; D. Đorđević, Milovan Milovanović, Pašić i Milovanović u pregovorima za Balkanski savez 1912. godine, Istoriski časopis IX–X (1959) 466–487. ↩︎

- A. Rastović, Britanska politika prema Srbiji u Prvom balkanskom ratu, Prvi balkanski rat. Društveni i civilizacijski smisao, I, prir. A. Rastović, Niš 2013, 73‒86; A. Rastović, Odjek Prvog balkanskog rata u britanskom parlamentu, Prvi balkanski rat 1912–1913: istorijski procesi i problemi u svetlosti stogodišnjeg iskustva, Beograd 2015, 213–223. ↩︎

- J. Cvijić, Izlazak Srbije na Jadransko more, Glasnik Srpskog geografskog društva 2 (1913) 192‒204. ↩︎

- In his address to the National Assembly in September 1912, Nikola Pašić gave the most accurate definition of Old Serbia. He stated that the term existed from the 19th century when the Principality of Serbia became a recognisable political entity in geographical maps. By then, cartographers had to find the adequate term for all regions outside of the Principality which were parts of the medieval Serbian empire. Consequently, the term Old Serbia spread to all regions which remained under the rule of the Ottoman Empire: Kosovo and Metohija, the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, the northern part of Macedonia until the Vardar river, the north western part of the Shkodër vilayet with the northern part of the Adriatic coast, including Durres, Alessio, San Giovanni di Medua and Valona (Arhiv Jugoslavije, Zbirka Jovana

Jovanovića Pižona, br. 80, fas. 1, arh. jed. 128‒129). ↩︎ - D. M. Dinić, Prvi put kroz Albaniju sa Šumadijskim odredom 1912, Kragujevac 1922, 92; J. Cvijić, op. cit., 192‒204. ↩︎

- V. G. Pavlovic, op. cit., 103 ↩︎

- Despite all efforts, Italy did not have a chance to persuade Austria because article 25 of the Treaty of Berlin gave Austria-Hungary the permission to build railway lines by itself. The draft of the Austrian railway plan went in the direction Thessaloniki – the Danube, and was developed by Benjamin von Kállay in 1900 and accepted by Count Aehrenthal in 1907. The annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina brought Vienna one step closer to the achievement of the project and thus alienated the opposing states from its project. Looking at the map, these two railway projects intersected with each other under 90 degrees (V. G. Pavlovic, op. cit.,

102–103; F. Šišić, Predratna politika Italije i postanak Londonskog pakta (1870–1915), Split

1933, 56–57). ↩︎ - Austro‐Italian Agreement concerning Albania 1900, The secret Treaties of Austria‐Hungary 1879‒1914, ed. by A. F. Pribram, Oxford University Press 1920, № 19, 196‒201; Les Archives diplomatiques du ministère des Affaires étrangères (AMAE), Correspondance politique et commerciale, Nouvelle série (1896‒1918), susérie Turquie, doss. 243, № 241, Rome, le 10 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- Đ. Đurić, Nikola Hartvig – portret ruskog diplomate u Srbiji 1909‒1914, Prvi balkanski rat i

balkanski čvor, ur. M. Pavlović, Beograd 2014, 267‒276; Đ. Đurić, Ruski poslanik u Srbiji Niklaj

Hartvig i balkanski ratovi, Prvi balkanski rat 1912/1913: istorijski procesi i problemi u svetlosti

stogodišnjeg iskustva, ur. M. Vojvodić, Beograd 2015, 203‒212; British Documents on the

Origins of the War 1898–1914 (BD), vol. IX, part II, ed. by G. P. Gooch and H. Temperley,

London, 1934, № 24, Sofia, October 13, 1912, 17‒18; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 268, № 32,

Sofia, le 1er mai 1913; AMAE, NS, Bulgarie, doss. 9, № 150‒152, Sofi a, le 12 janvier 1914. ↩︎ - Arhiv Srbije (AS), lični fond Milovana Milovanovića, MM–33, “Istorik pregovora za zaključenje Srpsko-bugarskog ugovora od 29. februara 1912“, Beograd, 31. mart/13. april 1912“, prepisao načelnik MID-a J. Jovanović, Beograd, 31. mart/13. april 1912. ↩︎

- Манифест към българския народ, Балканските войни по страниците на българския печат 1912‒1913Sir G. Buchanan, My mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories, I, London–New York–Tornoto–Melbourne 1923, 64; M. Ekmečić, Ratni ciljevi Srbije 1914, Beograd 1973, 35. ↩︎

- M. Ekmečić, op. cit., 35. ↩︎

- AS, lični fond Milovana Milovanovića, MM–33, “Istorik pregovora za zaključenje Srpsko bugarskog ugovora od 29. februara 1912“, Beograd, 31. mart/13. april 1912“, prepisao načelnik MIDa J. Jovanović, Beograd, 31. mart/13. april 1912. ↩︎

- B. Stojić, Francuska i balkanski ratovi (1912–1913), 66–87. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 239, № 11, SaintPétersbourg, le 16 octobre 1912; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 247, № 138‒154, Londres, le 29 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- Grčka objava rata ‒ kraljeva proklamacija, Samouprava, № 227 (8/21. oktobar 1912) 2; Bugarska objava rata Turskoj, Balkanski ugovorni odnosi, I, № 123 (17. oktobar 1912) 319; Манифест към българския народ, Балканските войни по страниците на българския печат 1912‒1913, подбрала П. Кишкилова, София 1999, № 6, 40‒41. ↩︎

- S. Skoko, Vojvoda Radomir Putnik, I, Beograd 1985, 244; Ž. G. Pavlović, Udeo Srbije u balkanskim ratovima 1912. i 1913. godine, Godišnjica Nikole Čupića 44 (1935) 92‒105. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 242, № 184, Vienne, le 4 novembre 1912 ; D. Đorđević, Izlazak Srbije na Jadransko more, 36–37. ↩︎

- Milić Milićević, Rat za more. Dejstva srpskih trupa u severnoj Albaniji i na primorju od 23. oktobra 1912. do 30. aprila 1913. godine, Beograd 2011, 86–99. ↩︎

- R. Poincaré, Les Balkans en feu, II, 114‒117; B. Stojić, Saznanja velikih sila o stvaranju Balkanskog saveza 1912. godine, Istorijski časopis LXV (2016) 385–402. ↩︎

- A. Rastović, Britanska politika prema Srbiji u Prvom balkanskom ratu, 73‒86. ↩︎

- G. Merlicco, La calda estate del 1940. La comunità italiana in Tunisia dalla guerra italofrancese all’armistizio, Altreitalie 53 (luglio – dicembre 2016) 29‒59; N. B. Popović, Srbija i carska Rusija, Beograd 2007, 40. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 243, № 240, Rome, le 10 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 244, № 124, Rome, le 13 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- D. Đorđević, Izlazak Srbije na Jadransko more, 39; D. Stevenson, Armaments and the coming of War. Europe 1904‒1914, Oxford University Press, 2004, 236; R. Poincaré, Au service de la France ‒ Neufe années de souvenirs, Tome II: Balkan en feu: 1912, Paris 1926, 332‒333. ↩︎

- D. Đorđević, Izlazak Srbije na Jadransko more, 65; Documents diplomatiques français (1871‒1914) (DDF), 3e série (1911‒1914), Paris 1934, t. IV, № 486, Belgrade, le 18 novembre 1912, 493; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 247, № 138‒154, Londres, le 29 novembre 1912; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 246, № 75, SaintPétersbourg, le 22 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- B. Ratković, M. Đurišić, S. Skoko, Srbija i Crna Gora u Balkanskim ratovima 1912–1913, I, Beograd 1972, 134. ↩︎

- BD, IX–II, № 173, Vienna, Novembre 10, 1912, 130; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 245, № 225‒227, Trieste, le 20 novembre 1912. ↩︎

- Dokumenti o spoljnoj politici Kraljevine Srbije1903‒1914, knj. V, sv. 3 (5/18. oktobar ‒ 31. decembar/13. januar 1913), prir. M. Vojvodić, Beograd 1981, № 289, 403‒404, D. Đorđević, Izlazak Srbije na Jadransko more, 85. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 247, № 66, Londres, le 27 novembre 1912 ; AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 249, № 18, Londres, le 9 décembre 1912. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 250, № 69‒72, Londres, le 17 décembre 1912. Russia tried to split the so-called Albanian question into two separated ones: Serbia’s request for the port on the Adriatic Sea and the question regarding the future status of Albania. Austria-Hungry opposed it firmly so those two different questions were discussed as a single question. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 250, № 69‒72, Londres, le 17 décembre 1912. ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 243, № 260, Munich, le 10 novembre 1912. France and its ambassador in London Paul Cambon fought most vigorously against Austria and Italy to place themselves as the powers most entitled to the election of the Albanian ruler. Cambon argued that a weak prince without money and authority and “imported” from a small kingdom could not endure in the country such as Albania for more than a couple of months. He was quoting the report of French military attaché in Serbia Pierre Victor Fournier who said that there were parts of Albania where Turks never stepped foot (AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 295, № 79‒85, Londres, le 9 mai 1913; D. Vujović, Francuski vojni ataše, pukovnik Furnije, o operacijama oko Skadra 1912. i 1913. godine, Oblasti Stare Raške krajem XIX i početkom XX veka, ur. P. Vlahović, S. Gojković, Prijepolje 1994, 267‒302). ↩︎

- The memoirs of Ismail Kemal Bey, London 1920, 379. ↩︎

- AMAE, FN, J. Cambon, doss. 50, № 249, Berlin, le 2 décembre 1913. Despite that fact, Prince Wied, who finally arrived in his realm in spring 1914, did not adapt very well in the Albanian environment. Ismail Kemal Bey and other Albanian leaders wielded their influence all over the country. The situation became more difficult with the outbreak of WWI and caused Prince Wied to flee the country in September 1914 and never to return (M. Kasmi, Albania during World War I (1914–1918), Vojnoistorijski glasnik 1 (2016) 45–66). ↩︎

- AMAE, NS, Turquie, doss. 295, № 223‒227, Londres, le 1er août 1913. ↩︎

- B. Stojić, Francuska i stvaranje albanske države (1912–1914), Prvi balkanski rat 1912–1913: istorijski procesi i problemi u svetlosti stogodišnjeg iskustva, ur. M. Vojvodić, Beograd 2015, 187–201. ↩︎

- G. Merlicco, Luglio 1914: L’Italia e la crisi austro‐serba, Roma 2018, 165–203. ↩︎