Nino Delić

Abstract: This paper deals with the census of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci of 1821, analysing the demographic data for the Arad, Timişoara and Vršac Eparchies in particular. Research in the former Archives of the Metropolitanate reveals that the count was actually taken in 1821 (Arad and Vršac) and 1822 (Timişoara). The Orthodox population in these eparchies consisted of Serbs and Romanians. The importance of the census lies in the fact that it included the ethnic (linguistic) composition of the population, which is a rare case. In the Arad Eparchy and the eastern parts of the other eparchies, a Romanian majority was registered (classified as Vlachs). The calculated data reveal that there were also some differences in household structure and size between Serbs and Romanians. On average, Romanian households seem to have been smaller than the Serbian ones, especially in northern parts of the area. Spatial differences are shown, with household size and the number of married couples per house (number of nuclear families) rising towards the west and south of the Banat region. The role of the government in Vienna in the process of census taking in the Metropolitanate remains unclear. It appears that the authorities were at the very least aware of the main results of the census. The possibility that the count was partly ordered by the state has to be verified by further research.

Keywords: Metropolitanate of Karlovci, census, demographics, Arad Eparchy, Timişoara

Eparchy, Vršac Eparchy, 1821, Serbs, Romanians

This study is part of a broader research project about the historical demographics of the Serbian population in the late modern period. Collecting reliable data is a key task and prerequisite for any demographic research. In the case of the early 19th century Habsburg Empire, censuses and other forms of population registers managed by the Metropolitanate of Karlovci happen to be not just an excellent, but generally the only available source for studying the population of the Orthodox community1.

The Orthodox population of the Empire was not ethnically homogeneous. Consequently, some deductions regarding the demographic characteristics of different ethnic groups are possible. In the eastern eparchies of the Metropolitanate, Serbs and Romanians (the two dominant Orthodox groups) often lived together in the same parishes, villages and cities. Most statistical materials from the former Metropolitanate archives do not offer any kind of information about the ethnic composition of the population, thus other sources are required to reach reliable results. Detailed demographic research to reveal the differences between Serb and Romanian populations is therefore rather complicated, and frequently outright impossible. The 1821 census is an exception, as it constitutes a source of demographic data by ethnicity of remarkable quality. The Orthodox population is classified by language/ethnicity into Serbs, Vlachs (Romanians), Greeks and Macedo-Vlachs (Tsintsars). The dating of the census is rather loose, but its origin is in the 19th century. In reality, it is a combination of statistical reports from the eparchies which are based on counts conducted in the period 1820‒1822. Still, it is useful and justified to maintain the dating and designation of the census as a whole commonly used in literature, but it is necessary to use the correct year if single eparchies are considered and in case the data are used in mathematical equations2.

The Metropolitanate of Karlovci kept various types of population registers of its congregation. From time to time, actual censuses of the population in parishes, protopresbyterats and entire eparchies were ordered. The main reasons for such actions were efficient taxation, administrative reforms, overview of church resources and properties, etc. This type of data was important for the policy of the church in relation to the state, i.e. to the central government in Vienna and its subordinates in Buda and elsewhere. Establishing or maintaining any kind of church-related institutions (parishes, places of worship, communes, schools, etc.) was virtually impossible without the consent of state officials. Official requests for approval for their founding contained evidence that these kinds of institutions were necessary in some regions because of the population structure. It seems that, in some cases, state authorities used existing data and instructed the Orthodox Church to collect additional statistics for the needs of the government.

Population statistics in Hungary during the first half of the 19th Century

The collection of population data using the resources of the Church seems to have been of huge importance to some authorities, since no state-run census could be carried out in the Lands of the Hungarian Crown in the first half of the 19th century due to the obstructions by the Diet of Hungary. Empire-wide censuses of Joseph II (1784-1787) could not be repeated until 1850/51. The only partial exceptions were the 1804/05 non- noble resident and 1826-28 land-tax censuses; however, these did not count the entire population and lack many important data. The attempt to establish some sort of permanent population registers based on the 1804/05 census which would be adjusted annually failed quickly. This does not imply that population statistics were not collected, presented, analysed and included in the public political debates of the time3. On the contrary, in Hungary in the first half of the 19th century new issues emerged, as ethnic and national identity became the basis for political regrouping and societal restructuring. Information about the racial, ethnic and religious composition of the country was in high demand, but the state had issued no official publications on this topic. At this time, numerous population studies regarding Hungary, written by scholars from the Empire, were published and became widespread. The origin of the data these „private statisticians” used for their works remains for the most part unknown. In some cases, complicated and unreliable calculations were used to project the number and structure of the population, but in some particular works very detailed figures were presented as a result of fresh and trustworthy, albeit unspecified sources.

Among the many „private statisticians”, one has to be mentioned in particular – Ján Čaplovič. The famous ethnographer, lawyer and writer of Slovak origin spent a large part of his life collecting topographical, historical, statistical and other material, using it to publish an impressive number of works on the ethnic and religious structure of Hungary4.

One of his books, dated 1819, also includes a detailed statistical table of the Metropolitanate based on data from 1797. The most interesting fact about these statistics is that they present the ethnic (or linguistic) structure of the population by eparchy. While Čaplovič did not reveal the exact source of the data (some „census” is mentioned), a comparison with the original documents from the former Metropolitanate archives in Karlovci proves that a church census indeed happened that same year. In the same work, Čaplovič mentioned that he had received some information about the city of Osijek from his „friend” Paul Beniczky, who happened to be the secretary of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci at the time. There is probable cause to believe that he received the statistical data from him as well5. In fact, the summary results of the census in the archival documents perfectly match the printed numbers. The only noteworthy, but key difference is the way the linguistic (or in an indirect way ethnic) structure is presented. In the archival documents, the population structure of each parish (by language) was not presented as exact numbers. Instead, a separate column was used to describe the linguistic character of the parish, noting if it was „Serbian”, „Vlach” or mixed „Serbian/Vlach”, etc. Some other remarks as to the approximate share of the mentioned linguistic groups as well as of Greeks and Tsintsars were made as well6. On the other hand, Čaplovič presented precise numbers by language/ethnicity. It is not clear by which method he reached the printed results, but it appears he simply redistributed the total population in mixed parishes, dividing it equally across the above linguistic groups. In a similar way, he obviously did so for the more problematic parishes with a complex ethnic structure using information from the remarks. The printed results are therefore not accurate and it is questionable if they can or should be used for scientific studies7. Still, the case of the 1797 census shows that the Metropolitanate was paying significant attention to the issue of linguistic/ethnic composition of the parishes as early as at the end of the 18th century. It should therefore be no surprise to discover that this kind of practice continued in the first half of the 19th century. Another famous „private statistician”, the forefather of Hungarian official statistics, Elek Fényes published a number of works trying to reconstruct the religious and ethnic composition of all Lands of the Hungarian Crown in detail8. Since no official data existed in the early 1840s, he used the recently published „schematismuses” of the Catholic Church in Hungary and censuses from the Military Frontier to obtain information on the Orthodox population. In one of his works, Fényes argued that he had to use them for lack of other up-to-date sources. He was surely aware of the fact that Catholic schematismuses were not an entirely reliable source of data on non-Catholic population. In fact, in the same work he informed the reader that a census of the Orthodox Metropolitanate took place in 1821, but apparently he considered these data obsolete. He also drew attention to a small remark made in an article published in the „Pressburger Zeitung” newspaper, where some fresh data on the Orthodox population in 1839 is mentioned9. The only data he used from the 1821 census is the total number of Orthodox Christians in Hungary. This number perfectly matches the totals we found in the original archival documents10.

The fact that no real count of the entire population was taken in Hungary during the first half of the 19th century does not mean that state authorities did not have an interest in that kind of information. The central government in Vienna was actually monitoring the situation quite closely. In the Military Frontier, which was directly administered by the central government, a permanent population register system was introduced in 1815 and censuses were conducted frequently thereafter. Beside the fact that the main motive for such a procedure was the conscription of males for military service, other, obviously political reasons forced the administration to collect information of little importance for military purposes, such as information on religious denomination and, ultimately, nationality of the population. At least for the years 1818-1819 the „nationality” (i.e. belonging to a linguistic group) of the population of the Banat Frontier was included in the inquiry11. In the following decades, the Banat section of the Frontier was reformed, and regiments were divided according to ethnic composition. In the 1820s the central government in Vienna tried to establish some kind of central statistical bureau, with jurisdiction over the entire Habsburg domain. Finally, in 1829 the Direction of Administrative Statistics (as it was named from 1840) was founded, but had no real authority in the Hungarian part of the Empire until the 1850s. Since the year it was established, the Direction printed an annual statistical yearbook (confidential – for internal administrative use only in the beginning) containing the most important data. The first edition was supposed to contain a special table showing the „national” composition of all parts of the Empire, but it was not completed. From the second edition onward, this classification was completely missing. For the Lands of the Hungarian Crown, the editors admitted there was no way to learn the exact number and religious composition of the population since no real census had been taken for decades. Instead, they offered a projection of the population based on unreliable data from Catholic schematismuses and growth rates calculated from old Josephinian censuses12. In the case of the Orthodox Church, state authorities and private statisticians could not count on statistical publications of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci since they simply did not exist. It is revelatory that the very first statistical publication – schematismus – of the Metropolitanate was in fact published by the government and not a Church institution. In 1844 and 1847, the University of Buda published two „schematismuses” of the Orthodox Church, edited by a councillor of the Office of the Hungarian governor general in Buda (Statthalterei, Locumtenentia), effectively making them official state editions13. Both works are well-known to historians, but it is less known that the source of data was the Metropolitanate itself, once again collecting statistical reports from eparchies and combining them into an overview. As in the case of the 1821 census, not all published data truly referred to the designated years. To gain correct results for complex demographic indicators (such as year-to-year growth rates), precise dating is essential and almost impossible without the use of original archival sources14. Finally, in 1850/51 the central government organized and carried out the first census in the whole Empire at the same time using a unified methodology. It was also the first and only count when the population was asked about their national identity. This once again shows the importance the authorities in Vienna ascribed to the question of ethnic and national composition of parts of the Empire15.

Statistics, Serbian-Romanian relations and government policies

The Metropolitanate of Karlovci was the highest religious authority for Orthodox Christians in the Empire. The heterogeneous ethnic structure of the Orthodox population

made it difficult for the Metropolitanate to fulfil its aim of acting as a „national” institution, as it was actually classified due to imperial privileges obtained in the 17th and 18th centuries (Institution of the „Rascian/Serb” or „Illyrian” nation)16. This problem was evident in eastern eparchies in particular, where both Serbs and Romanians lived. The issue of the language used in ceremonies and schools, and the proportional nomination for priests based on ethnic structure of the parishes evolved into high priority disputes as early as the end of the 18th century. At the „National and Church Congress”, the highest assembly of the Orthodox Illyrian population and Church in the Habsburg Empire, held in Timişoara in 1790, the Bishop of Transylvania Gerasim Adamović protested, asking for Romanians to be recognized as a nation and the Serb-Illyrian privileges to extend to them as well17. The electorate of the Wallachian-Illyrian Military Frontier canton instructed its delegates in the Congress to demand fair representation of Illyrians (Serbs) and Wallachians (Romanians) in Court councils and free access to all schools for members of „both nations”18. At the beginning of the 19th century, eastern Banat parishes started complaining about the poor status of Romanian priests and the Metropolitanate disregarding the need for the education of the Romanian population. After the death of Pavle Avakumović in 1815, the seat of the Arad Bishop became vacant and members of the Romanian clergy and intelligentsia demanded the office to be permanently appointed to a Romanian by nationality. The Metropolitanate was not content with such a policy. As a matter of fact, Metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović suspected that the true instigator of the dispute was the Viennese government, in a bid to weaken the power of the Orthodox Church and finally split it into two separate churches. In the 1820s Stratimirović faced the challenge of resolving the issues of language and alphabet used in liturgy and schools in the Eparchies of Arad, Timişoara and Vršac. In 1822 he stated that nobody can or wants to hinder the Romanian people, who were the majority in the Timişoara Eparchy, to learn religious sciences in their own language, but that the main problem lay in the lack of qualified personnel. In 1828 Stratimirović finally ceded, appointing the first Romanian for the seat of Arad Bishop, Nestor Ioanovici; thereafter, the knowledge of the Romanian language was made necessary for the bishops of Timişoara and Vršac, but disputes continued until the final split in 1864-186819.

Considering the unresolved problems in Serb-Romanian relations, knowledge about the precise ethnic composition of the eparchies was of utmost importance. The

Metropolitan himself reasoned that the Romanians made up the majority in the Timişoara Eparchy. That was a fact that he could have stated as common knowledge, but at that point he already had the census results from 1797, and in particular those from 1821 which confirmed it. It should be noted that the 1797 census contains detailed data on the resources of the Orthodox Church (personal data on priests and bishops, state of objects of worship, etc.), while the count of 1821 was focused on the population. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the lasting problems in the eastern eparchies drove Metropolitan Stratimirović to order a new general count, with detailed information about population ethnicity in 1821. The role of the state in these matters is still ambiguous. The 1797 census may have been ordered by the state, as some researchers believe20. Similarly, in the case of the 1821 census, some evidence indicates that the results were specifically prepared for the state authorities and transmitted to them. A separate summary document was attached to the main census file. It was written in German using Gothic/Kurrent letters by the secretary of the Metropolitanate, Paul Beniczky. The summaries present the ethnic composition of the Metropolitanate by eparchy, county (Comitat) and Military Frontier regiment. There is no other reason for the Metropolitanate to create such a document than the intent or obligation to expedite it to the authorities using German as the official language21. It is certain that the Viennese government was interested in such data, as they were also collected two years before in the Banat Frontier. Some twenty years later, similar statistics were obtained by the Governor’s general office in Buda in cooperation with the Metropolitanate. Still, it remains unclear whether Vienna initiated the 1821 census or not. Finally, statistics were crucial in the process of splitting the eparchies between Serbs and Romanians in 1864-1865. The National and Church Congress in 1865 demanded, once again, up-to-date data from the eparchies to accomplish the goal of fair division of the parishes and effective reform of the clergy22.

The Censuses of 1820-1822 (1821): Arad, Timişoara and Vršac Eparchies

The original documents of the 1821 census form a huge dossier, composed of separate files for each of the nine eparchies23. Usually, each file contains a short letter (answer) from the Bishop to the Metropolitanate and a special form-sheet containing statistical data. From the reply letters we learn that in February and March 1821 the

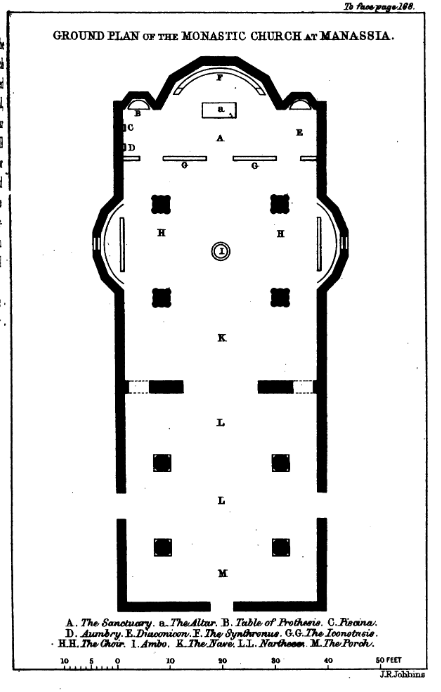

Metropolitanate sent a demand to all eparchies to submit the latest data about the clergy and population. Most bishops responded quite promptly, within a few months, and submitted the data obtained in the 1820-1822 period24. The form-sheets are uniform, handwritten using the Serbian language in the Cyrillic script25. The columns (from left to right) first identify the territorial scope for the statistical data: name of County or Military Frontier regiment – name of the protopresbyterat – name of place (sequence number, name of parish church / parish, name of filial church, if any). Parish church names were actually names of settlements where a church commune was established. Filial church names were names of settlements which were dependent on the previously named parish. Secondly, statistical data in columns presents the number of: Churches, Parish-Priests, Chaplains; Deacons, Houses, Married Couples; Men, Women, Sum of both (men+women). Further, four columns inform that „among all of them” (men and women) there is the following number of: Serbs, Vlachs, Greeks, Macedo-Vlachs. The term Vlachs unquestionably means Romanians, and Macedo-Vlachs (Makedovlasi in original) stands for Tsintsars. Classification criteria are unknown, but most probably the mother tongue of the population was used to identify the ethnicity of the counted population. Finally, in the right margin, a separate column for additional remarks is inserted. A summary row is inserted after each protopresbyterat, and a total summary row at the end of each page as well. At the end of each sheet, an overview for the whole eparchy with summaries by protopresbyterat is shown. There are corrections made with red ink on all sheets. Those corrected numbers (in red ink) were finally put into separate summaries done by Paul Beniczky. In some cases, the corrections are also inaccurate. Difficulties with addition in the pre-calculator and pre-PC era are of no surprise and wrong results frequently occurred in statistical publications. Some errors are present in the summary overviews at the end of the sheets as well. We corrected them for the purpose of this research, but we also remind that minor changes will probably appear in future studies, as the complete sheets are going to be transcribed, digitised and revised.

The sheets contain a huge amount of data, and a lot of effort and time are needed to complete the rectification process. The Arad Eparchy sheet has 66 pages and almost 550 rows of data alone. Still, we do not expect major deviations that would change the main conclusions already made in this paper26.

Tables 1-3 show data as they were recorded in the summary overviews at the end of the sheets (with corrections made in red ink), with our remarks about certain errors.

The names of places (protopresbyterats) in the tables are as specified in the original documents (but converted into Latin script). The present-day names of the places are in footnotes.

a27a

a34

We managed to calculate important social and demographic statistical indicators using the census data (Tables 4-6). The average household had 5 to 6.5 members, depending on the area. If we compare the number of married couples and houses, a pattern emerges, since more nuclear families (married couples) used to live under the same roof in areas with larger households. The relatively low share of married people in the population clearly suggests that the overall number of children must have been high. Still, some significant differences arise when comparing the data in detail. The Protopresbyterats of Arad and Belineš show a different structure, since the size of households was rather low in both of them, but the number of married couples was quite high. This indicates that nuclear families were quite small in size there, i.e. there was a low share of children in the population. This is additionally corroborated by the high share of married people in the population. In general, the situation in the Arad Eparchy was relatively different compared to the other two. In Arad, households were rather small (around 5 members), usually consisting of one nuclear family (only 1.24 couples per house), with a larger segment of married people in the population (almost 48%). In the other two eparchies households had 6-6.5 members, nearly 1.5 couples per house and a lower share of married people (around 44%). This suggests that in the Arad Eparchy usually only one nuclear family lived in a house, with fewer children (probably around two). In the other eparchies, households were obviously composed of more than one nuclear family and had more children (around 2.5). A comparison of the total population with the number of married people shows that in the Arad Eparchy there were 4.2 people per one couple (and in the others – 4.5). The differences were not significant only in terms of spatial distribution. Household size was notably larger in areas with a large Serbian community. This could probably be explained by the fact that Serbs lived in the major cities of western Banat (Kikinda, Vršac, Bečkerek, etc.), and that city lifestyle led to a higher concentration of people in living quarters. It remains unclear how „houses” in urban areas, with more than one apartment and several families residing there, were actually classified during counts. Nevertheless, it is surprising to see that the typical household in the Protopresbyterat of Pančevo had almost 10 members, while in Bela Crkva it had less than 7. Both protopresbyterats were urban-shaped areas located in the Military Frontier. Both cities had the same status of free military communities, they are located in the Banat Plain and the distance between them is less than 100 km. By contrast, the typical household in the Protopresbyterat of Arad had „only” 5 members.

Among all indexes, the gender ratio seems to be quite balanced. Differences may be observed if we compare certain protopresbyterats with unusual gender structure. For

instance, a significant majority of men can be identified in Belen, and of women in Peštiš. In general, men outnumbered women, which does not correspond to the contemporary gender structure. The reason for this is unclear. Counting errors are often used to explain such a phenomenon in 19th century statistics. We do not believe that errors are responsible for these results, but that men really did outnumber women, as most demographic research indicates for the Balkans in that period.

There are numerous possibilities for further research. All presented calculations are possible at parish level, as is the comparison of results between counties and Military

Frontier regiments, etc. Additional types and combinations of data – number of churches, deacons, chaplains per household inhabitant, etc. – can and should be computed and analysed.

- The unofficial project is carried out by a number of researchers at the Institute of History in Belgrade. Collection, examination and publication of historical demographic data from the early modern period until World War I are part of the activities. ↩︎

- The original documents of the census form a file kept in the Archives of the Serbian Academy of Sciences in Sremski Karlovci [Arhiv Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti u Sremskim Karlovcima = ASANUK] as part of the Metropolitanate archives collection [Mitropolijsko-patrijaršijski arhiv = MPA]. A separate summary document written in german is attached to the file and was published by Slavko Gavrilović. ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1821/102; Slavko Gavrilović, Sumarni

popis pravoslavnih Karlovačke Mitropolije 1821. godine, „Zbornik za istoriju Matice srpske”, vol. VII (1973), p. 129-133. ↩︎ - Adolf Ficker, Vorträge über die Vornahme der Volkszählung in Österreich: gehalten in dem vierten und sechsten Turnus der statistisch-Administrationen Vorlesungen, „Mittheilungen aus dem Gebiete der Statistik”, vol. XVII (1870), p. 8, 16, 19-20; Nino Delić, „Tafeln zur Statistik der Oesterreichischen Monarchieˮ (Tabele za statistiku Austrijske Carevine) 1828–1848, kao izvor za istoriju srpskog naroda u Habzburškoj monarhiji [infra: „Tafeln und Statistik …”], „Srpske studije”,

vol. II (2011), p. 200-201; Péter Őri, Levente Pakot, Census and census-like material preserved in the archives of Hungary, Slovakia and Transylvania (Romania), 18-19th centuries, MPIDR Working Papers WP-2011-020, Rostock, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, 2011, p. 11-12, 33. ↩︎ - Ján Čaplovič (Johann von Csaplovics in German), 1780-1847. He worked for some time in Vienna at the Court Chancellery for Hungary and later as a commissar for the Bishop of Pakrac in Slavonia. He probably had access to confidential and internal documents which were not available to the general public and other statisticians; Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich (ed. Constantin von Wurzbach), 3. Theil, Wien, Verlag der typogr.-literar.-artist. Anstalt (L. C. Zamarski, C. Dittmarsch & Comp.), 1858, p. 44–46 ↩︎

- Csaplovics Johann von, Slavonien und zum Theil Croatien, I. Theil, Pesth, Hartlebens Verlag, 1819, p. 22; Ibidem, II. Theil, Pesth, Hartlebens Verlag, 1819, p. 68-71; ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1797/33. ↩︎

- ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1797/33. See also: Dejan Popov, Popis parohija i vernika u Eparhiji temišvarskoj 1797. godine, „Banatski almanah 2015”, 2015, p. 151-160. ↩︎

- Čaplovič’s results were used by other „private statisticians”. Pál Magda, another ethnographer of the first half of the 19th century, frequently cited Čaplovič in his works. Identical summary data by language/ethnicity of the population of the Metropolitanate were published in his famous description of Hungary (Paul Magda, Neueste statistisch-geographische Beschreibung des Königreichs Ungarn, Croatien, Slavonien und der ungarischen Militär-Grenze, 2nd ed, Leipzig, Wigand`sche Verlags-Expedition, 1834, p. 114.). Magda also used to be the director of the Orthodox Gymnasium in Sremski Karlovci, and had therefore an excellent opportunity to establish close relations with the highest authorities of the Metropolitanate and obtain access to its archives; Petrović Kosta, Istorija Karlovačke gimnazije, Novi Sad, Matica srpska, 1991, p. 125-126. ↩︎

- Elek Fényes (Alexius Fényes in German), 1807-1876. He was a lawyer by profession, but spent a lot of time travelling and collecting statistical data on all parts of Hungary, and published them in several works, for which he was awarded by the Hungarian academy. In 1848, as part of the revolutionary government, he was the one who founded the Hungarian Statistical Office. He was later imprisoned, and after release continued writing and working as a journalist; Biographisches Lexikon

des Kaiserthums Oesterreich, 4. Theil, Wien, Verlag der typogr.-literar.-artist. Anstalt (L.C. Zamarski, C. Dittmarsch & Comp.), 1858, p. 177-179; Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon, Band. 1 – Lieferung 4, Wien, 1958, p. 298. ↩︎ - Alexius von Fényes, Statistik des Königreiches Ungarn, I. Theil, Pesth, Verlag der Trattner–Károlyschen Buchdruckerei, 1843, p. 46 ↩︎

- The totals match perfectly with the numbers in the summary document attached to the census files in the archives. The summary documents were published by Slavko Gavrilović; Alexius von Fényes, op. cit., p. 46; ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1821/102; Slavko Gavrilović, op. cit., p. 129-133. ↩︎

- The „national” (i.e. linguistic groups) were: Slavs, Vlachs (Romanians), Hungarians, Germans, Others; Nino Delić, Popis Banatske vojne granice 1819. godine, „Mešovita građa-Miscellanea”, vol. XXXV (2014), p. 67-79. ↩︎

- It is quite obvious that the editors had the intention to introduce tables about the national structure of the Empire, but dropped the idea due to a lack of data. For Hungary they showed marked initiative, recalculating the projection numbers of the population by religion year-by-year, noting in a remark that the basic data could be corrupt. It seems that the religious and ethnic composition of the Empire was of great importance to the policymakers in Vienna; Nino Delić, „Tafeln zur Statistik …”, p. 183,186, 200-201,181–208 ↩︎

- The income from selling the schematismuses had to be added to the funds of the Orthodox Church. Full title of the first edition: Universalis schematismus ecclesiasticus venerabilis, cleri orientalis ecclesiae graeci non uniti ritus I. Regni Hungariae partiumque eidem adnexarum nec non magni principatus Transilvaniae item literarius seu nomina eorum qui rem literariam et fundationalem scholarem ejusdem ritus procurant sub benigno-gratiosa protectione excelsi consilii regii locumtenentialis hungarici per Aloysium Reesch de Lewald excelsi consilii R. Locumtenentialis hung. Concilistam et I. Comitatus Strigoniensis tab. Jud. Assessorem pro anno 1843/44 redactus, Budae [infra: Universalis …].

The second edition was published under the same title except the year, which was changed to 1846/47. ↩︎ - The main file assigned to the councillor of the Office of governor general in Buda and editor of the schematismuses, Reesch de Lewald, is unfortunately missing from the Archives (ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1845/802).

For example: a comparison of the data in the Schematismus of 1846/47 and in archival documents of 1845 reveals that some numbers for the Eparchy of Karlstadt (Gornjokarlovačka Eparchy/Upper Karlovac Eparchy) match perfectly while others are different. This confirms that the common practice in the 19th century of simply „copying and pasting” data from year to year was customary in the Metropolitanate administration as well; ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1846/116; Universalis … 1846/47, p. 82-101. ↩︎ - Adolf Ficker, op. cit., p. 19-20. ↩︎

- The terms „Rascian”, „Servian” and „Illyrian” were used simultaneously in the imperial privileges, most often as synonyms meaning „Serbs”. See: Vladan Gavrilović, Diplomatski spisi kod Srba u Habzburškoj monarhiji i Karlovačkoj mitropoliji od kraja XVII do sredine XIX veka, Veternik, LDIJ, 2001, p. 8-42; Ljubivoje Cerović, Srbi u Rumuniji, Novi Sad, Matica Srpska, 1997, p. 149-150. ↩︎

- In Transylvania the Vienna government retained vital influence over Church matters and left the Metropolitanate only limited jurisdiction over the Eparchy. Gerasim Adamović was the last Bishop of Serbian origin. After his death in 1796 the seat remained vacant until 1810, when the Romanian Vasile Moga was elected in Turda and approved by Emperor Francis I; Ljubivoje Cerović, op. cit., p. 146-147. ↩︎

- It is abundantly clear that the electorate considered Illyrians and Wallachians separate nations, represented on a common level within the Empire; Vladan Gavrilović, Temišvarski sabor i Ilirska dvorska kancelarija (1790-1792), Novi Sad, Platoneum, 2005, p. 197-199 ↩︎

- Stratimirović identified the Preparandia (school) and its members in Arad as the source of the demands and complaints. He was struggling with the Viennese government over the control of priest education for decades, assuming that the state was trying to take over this privilege. He was receiving reports from the eastern eparchies that Vienna and the Greek Catholics were obviously forcing a split in the Metropolitanate by taking advantage of the unresolved issues with the Romanians; Slavko Gavrilović, Srbi u Habzburškoj monarhiji od kraja XVIII do sredine XIX veka, in vol. Istorija srpskog naroda, V/2,Beograd, Srpska književna zadruga, 1981, p. 41-42; Đoko Slijepčević, Istorija Srpske pravoslavne crkve, 2, Beograd, JRJ, 2002, p. 64-66, 108-110; Ljubivoje Cerović, op. cit., p. 144-145, 150-152. ↩︎

- Dejan Popov, Sveštenstvo Eparhije temišvarske 1797. godine, (1), „Temišvarski zbornik”, vol. VIII (2015), p. 93. ↩︎

- The summaries could have been sent to Vienna or the Military Frontier authorities, and perhaps to Buda as well; ASANUK, MPA, fond A, № 1821/102. ↩︎

- Goran Vasin, Sabori raskola: Srpski crkveno-narodni sabori u Habzburškoj monarhiji 1861-1914, Beograd, Službeni glasnik, 2015, p. 125; Uredba o uredjenju crkvenih, školskih i fundacionalnih dela grčko-istočne srpske mitropolije, odobrene previšnjim kraljevskim reskriptom od avgusta 1868, ed. Mita Klicin, Sremski Karlovci, 1909 ↩︎

- Transylvania is not among them, but Bucovina is. ↩︎

- The reply letters from Arad, Timişoara and Vršac are unfortunately missing. The statistical data were dated according to the indications made in the titles of each sheet (each title explicitly states the year to which the tables relate). ↩︎

- Except the Bucovina sheet, written in German using Kurrent letters ↩︎

- The largest error occurred in the case of the Timişoara Eparchy summaries. The numbers for the Žebel Protopresbyterat are confusing since the sum of men and women does not correspond to the total population. Comparing the numbers to the count of married couples and other censuses, we concluded that the problem is evidently the number of men and women, which is too small. The summaries by Paul Beniczky show the total population number as the sum of men and women, which is thus lower than in the original sheets. ↩︎

- per one couple (and in the others – 4.5). The differences were not significant only in terms of spatial distribution. Household size was notably larger in areas with a large Serbian community. This could probably be explained by the fact that Serbs lived in the major cities of western Banat (Kikinda, Vršac, Bečkerek, etc.), and that city lifestyle led to a higher concentration of people in living quarters. It remains unclear how „houses” in urban areas, with more than one apartment and several families residing there, were actually classified during counts. Nevertheless, it is surprising to see that the typical household in the Protopresbyterat of Pančevo had almost 10 members, while in Bela Crkva it had less than 7. Both protopresbyterats were urban-shaped areas located in the Military Frontier. Both cities had the same status of free military communities, they are located in the Banat Plain and the distance between them is less than 100 km. By contrast, the typical household in the Protopresbyterat of Arad had „only” 5 members.Tot Varad – Vărădia de Mureș; Vilagoš – Șiria; Boroš Jenov – Ineu (Jenopolis); Butin – Butin (Temesbökény); Kiš Jenov Chișineu-Criș; Zarand – Zărand; Halmađ – Hălmagiu; Veliki Varad – Oradea; Peštiš – Peștiș; Lunč – Lunca (Lakság valley); Pap Mezeu – Pomezeu; Belineš – Beiuș; Meziad – Meziad (in Remetea commune); Belen – Beliu. ↩︎

- Temišvar – Timişoara; Čakova – Ciacova; Žebel – Jebel; Fažet – Făget; Hassiaš – Hisiaș; Lipovo – Lipova; Čanad – Cenad (Rácz-Csanád); Velika Kikinda – Kikinda; Veliki Bečkerek – Zrenjanin. ↩︎

- This number is obviously too low and not correct. That is the fact in all parishes in the protopresbyterat. It seems that only the number of the total population was known precisely. ↩︎

- This number is obviously too low and not correct. That is the fact in all parishes in the protopresbyterat. It seems that only the number of the total population was known precisely ↩︎

- This is the original number. It was corrected to 18.561 using red ink (sum of men and women) but this cannot be real. It seems that the total number of the population and the ethnic composition were known precisely, but that information lacked on gender distribution. ↩︎

- Without data from Žebel Protopresbyterat. ↩︎

- Without data from Žebel Protopresbyterat. ↩︎

- Palanka – Banatska Palanka; Varadija – Vărădia; Karansebeš – Caransebeș; Mehadija – Mehadia; Lugoš – Lugoj. ↩︎

- Not possible to compute because the original numbers for men and women are false. ↩︎

- Computed without data for the Žebel Protopresbyterat. ↩︎