BoJ note: this is a text from the “Vjesnik u srijedu” (“Wednesday Herald”) newspaper from Zagreb of 10.06.1952. about judicial proceedings against Ustašas who operated in the Slana extermination camp on Pag Island, Croatia.

From June to August 1941, around 15,000 Serbs and Jews were killed in the “Slano” camp on Pag

By a twist of fate, seven Ustaša butchers ended up in the hands of justice after a full 12 years: Luka Barjašić, Slavko Baljak, Jadre Strika, Jere Fratrović, Bene Barić, Mile Didulica, and Ivan Kevrić. During three months in 1941, they participated as members of the 1st Company of the 5th Ustaša Battalion in the destruction of Serb and Jewish prisoners in the “Slano” camp on Pag.

Our intention in evoking those past events is not only to present dry facts, the horrors of committed atrocities, or courtroom reports, but to also highlight through this case the grotesqueness of a system, an ideology, which not only bloodthirstily destroyed humanity but also turned humans into professional killers, bestial monsters, whom even all the inquisitors of the Middle Ages would not be ashamed of.

Seven butchers stand before the court. However, many of their ideologues, battalion commanders, and soldiers are still strolling more than freely around the liberal-hospitable Western European world. They are waiting for “their moment,” but the fascist chimera, like a hundred-headed dragon, futilely licks its poisonous tongue. The tortured prisoners have long passed away, their tormented bones have long decayed, but we have not forgotten them. They are embedded in the foundations of this country, they are part of our lives, and, along with the Party and Tito, they signify peace and security on our borders.

“Confession” of Luka Barjašić

Where are you from, they asked. Why are you imprisoned?

– From Poličnik…

Silence fell among the prisoners. At that time, Poličnik had produced a large number of Ustašas. The newcomer explained that he was imprisoned because of a revolver found on him last night when he fired from the village, thinking that ‘Serbs from Smoković’ were attacking.

– And you, which faith are you, Croat or Orthodox?

For a start, that was enough. Furthermore, the newcomer was wearing Ustaša boots. To find out more; the prisoners, according to the plan, acted in unison.

– What Orthodox, damn them, they have brought us here.

And when Poljak explained that the Italians imprisoned him as an Ustaša, Luka Barjašić completely warmed up to him. And among the ‘Ustašas,’ a more intimate conversation began.

– Oi, Serbs, damn them, they paid me, I gave it to them.

– They did, damn them, to me as well, I skinned their beards alive.

– And what did you beat them with? How was it the first time? – The other day, we took 1,200 of them to Karlobag, and then to Oštarije.1 When we brought them to the pits – a pitiful sight. But no one could escape even if they had wings. We beat them and bludgeoned them in every possible way to save bullets. We bound larger groups together with wire, killed those at the edge first so that they would pull the rest down with them. Some jumped into the pit alive. We cemented the pits to ensure that no one came out alive. There were Jews from Zagreb, Orthodox2 from Obrovac and Knin, people from Gračac and Tribanj.

And it was there that Luka Barjašić, over the course of three days, recounted how he had gone to ‘Pavelić’s school’ right in 1941, how it was a bit awkward to kill for the first time, but later he could kill 5,000 at once. He spoke of the pits in Velebit, the beating and bludgeoning with rifle butts, the raping of women and girls.

– And why don’t you kill those Serbs under Velebit, damn them, Poljak asked again.

– We have. Recently on Pag, we killed an old woman and an old man (Poljak’s heart tightened).

– What are they like, he asked, concealing his excitement. And when Luka Barjašić began to describe them, he could no longer contain himself. He jumped on him like a wounded beast and began to strangle him.

– Ah, you Ustaša bloodsucker, you killed my father and mother…

Luka Barjašić’s ‘confession’ was over. The Italians sensed the commotion and moved Luka to another cell, then transferred him to Šibenik and onwards to Italy. Of the remaining prisoners, only Šolaja was sent with him to Florence and Parma. Everywhere, Šolaja exposed him among the prisoners as an Ustaša butcher. The prisoner boycott was received coolly by Barjašić. Later, he allegedly entered Italian service. They say the prisoners feared him more than any Italian guard.

Since then, Luka Barjašić’s trail has disappeared.

“Slano” Concentration Camp

It took a full eleven years for former prisoners to accidentally reunite at the fair in Benkovac. Luka Barjašić was arrested first, followed shortly by six other fellow villagers.

The testimonies of the accused, witnesses, and bystanders, reports from the State Archives in Rijeka along with the statement from the Italian health commission, letters, and confrontations, all fairly accurately reproduce the horrors of the Pag camp, the arduous life of the Pag internees, which often lasted no more than a few days, and the shared guilt of the accused.

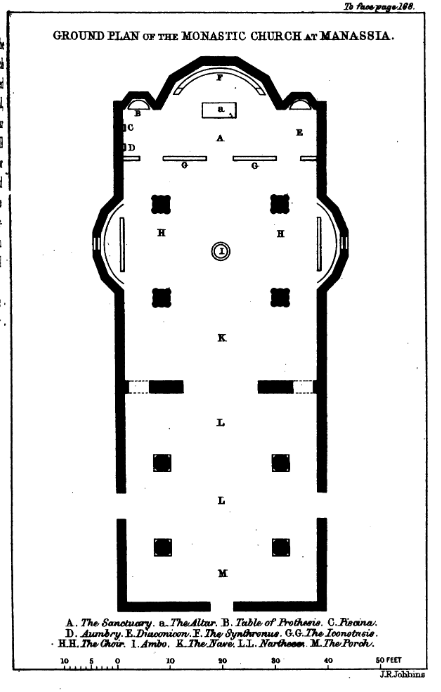

The “Slano” camp on the island of Pag was established immediately after the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia, at the end of May or the beginning of June 1941. “Slano” is a rocky plateau, essentially a basin surrounded by hills. Here, the fiercest winter winds from Velebit’s barren peaks descend, while in summer, an unbearable heat prevails. The area is completely bare, without any vegetation, without water, and thus uninhabited. By the sea, a few springs of brackish, non-potable water can be found. On the northern part of this plateau, over an area of approximately 200 x 150 metres, the Ustašas erected three wooden shacks enclosed by a single barbed wire fence.

Here Jews were accommodated. In the southern, smaller part, there were ten shacks for Serbs. The Serbs were fenced with a triple wire measuring three meters high and two and a half meters wide. Poorly constructed shacks did not protect from the wind and the rain. They slept on bare wooden bunks arranged in tiers. A few kilometers away, in the village of Metajna, there was a camp for women and children housed in homes (Dr. Triplat’s, Dr. Hvala’s, and one peasant house).

People from all parts of Croatia were brought to “Slano.” Jews, Serbs, Croats, women, children, and old people of all ages and all professions. The camp inmates were arriving in Gospić day and night, by trucks or sealed train wagons, and from there they walked to Karlobag, tied with wire and beaten with rifle butts along the way.3 From Karlobag, they were transferred daily by boats to Baška Slana to Sušac Bay, a camp a few kilometers away. The boat ride provided opportunities for various kinds of torture. To conceal what they were transporting, the Ustaše usually crammed the prisoners into the hold (the interior of the ship), and as they crammed 150 people in a space meant for 50, they walked over them, pushed them with oars and rifle butts so the boat could be closed.

As a result, the camp inmates sustained severe bodily injuries, broken arms, legs, ribs, and other parts of their bodies. The camp commander, the notorious Ventura Baljak from Poličnik, described by even the accused as one of the greatest butchers in Europe, would indulge in his bloodthirstiness in such situations by, for instance, slaughtering individuals, drinking their blood, and throwing them into the sea with a stone tied to their neck.

The prisoners were tortured with hunger, thirst, and hard labor. The food consisted of one loaf of bread for 30 people and a quarter liter of water with a few beans. The prisoners ate grass if they could get to it. When they would faint from exhaustion, they were beaten with rifle butts to regain consciousness. The sanitary conditions were drastically worsened by dysentery, especially among small children. The latrines, located ten steps from the shacks, consisted of a 10 cm deep longitudinal trench with only one side of the shacks raised by a half-meter high and 4-meter long wall, so the detainees were exposed to the guards’ view from all sides. There was no water for washing, and the drinking water was minimal.

In the terrible heat, naked and barefoot, without bread and water, they had to perform the hardest labor without any sense, to be as exhausted as possible. They worked in the quarry, built the road Baška Slana-Sušac, and carried barrels of water for the camp administration. Any disobedience was punished by shooting. The details of the torture are unknown. The accused stated that there was no torture, however, individuals from nearby places tell that the Ustaša after massacres always boasted about various atrocities. After the camp was dissolved, a bed made of barbed wire, presumably for torture, was found in the southern, Serb part.

In Metajna

There was nothing better, if not worse, for the women because they were women. They were kicked, cursed at with all kinds of profanities, and pelted with stones. The infamous camp commander Devčić “Pivac” personally took them for bathing on the Karlobag side of the shore and, on the way back, allowed his gang to choose among them. Even on their way to the execution site, these suffering women were not spared such “selections.” The “servants of God” also got their dirty hands involved in these criminal activities. Witness Ivan Festini states that in a small forest of Barbat, the raped and murdered daughter of Ognjen Prica was found. Don Krsto Jelinić, attributed to this murder, often visited the Metajna-Barbat women’s camp, raped, and murdered. Some of the defendants remember his visits to Slano, his arrangements, and his drunken binges with the camp heads. Priest Don Ljubo Magaš, the pastor from Barbat, boasted to witness Šime Maržić about how he, together with an Ustaša named “Pavica,” raped an eighteen-year-old Jewish girl, whom they both later killed.

Jelinić is on the run, but Magaš was caught and shot after Liberation for this crime. The occurrences in Metajna can be inferred from the traces left in the camp: scattered children’s shoes, hair on the barbed wire…

One day, a young Serb woman was brought into the Ustaša office in Metajna, who defiantly shouted at one of the Ustašas, “What are you so arrogant about, you bastards? Do you think the Reds are defeated?” The one-eyed commander of Metajna, Maks Očić, took the unfortunate woman towards “Dražica.”4 Shortly after, the sound of a pickaxe striking was heard. Her five-year-old son disappeared that same night. The horrifying story of the daughter of a Serbian officer who, during a massacre in Furnaža, offered her youth in exchange for a knife is surely not the only one.

In the last days, just before the camp was taken over by the Italians, a transport of women arrived in Metajna. Because of the presence of the German-Italian commission, they were immediately transferred to Caska (a village near Barbat) and the following night moved somewhere to the Paška Vrata, where the trenches for corpses were located. Witness Jakov Dokazić, an Ustaša guard from “Slana,” believes they were all killed that same night, as he heard the Ustašas returning to “Slana” singing in the morning.

Just before the camp was disbanded, all the women were moved to the communal shacks in “Slana.”

From the Knife to the Procession

All the prisoners were sentenced to death; it was only a matter of time. When? Every night at sunset or before dawn, a group of Ustašas would lead the camp inmates, in larger or smaller groups, to the execution sites. It is unknown how many such executions took place. The accused speak of thousands killed in Velebit and the Furnaža area, and witness testimonies and the discovery of bodies add thousands more to those numbers. The camp Ustašas did not only kill the inmates but also rampaged through the surrounding villages, plundering and stealing, and abducting the Serb inhabitants.

Witnesses mention the murders and abductions of villagers from Šibuljina, Počitelj, Divoselo, Tribanj, and other nearby villages, often hearing cries and the staccato of machine guns. Every 8-10 days, the inmates were called to “prepare to go home,” for “work in Germany,” to “report for medical exams,” or to be transferred to “another” camp, and then those who reported were killed or shot. Ustaša member Vjekoslav Pačini, known as “The Judge,” recounted on August 8, 1941, that they often lined up a hundred people and mowed them down with a machine gun. When orders were given to avoid gunfire, they killed them with knives.

Among these mass murders, the accused only admit to the massacre of Jews in Velebit (on two occasions) and the massacre of Serbs in the Furnaža area, a few kilometers behind Sušac Cove – deeds for which they are specifically charged. According to the confession of the accused, each participated in the murder of only one prisoner.

At the end of July or the beginning of August, a group of Ustašas, including the accused, transferred by boat a group of several hundred Jews, men, women and children, from Pag to Barić-draga on the Velebit coast. From there, they were taken to Velebit where they were killed on the same day. Details of that massacre can be found in all the statements. After Baljak Ventura eagerly demonstrated how it is done, all the Ustašas were called by name and had to kill the prisoners in turn. When one managed to break away and escape, they began to beat them with hammers. This is how the remaining women were killed. According to the statements of the accused, trips to Velebit happened several times, but they did not participate, except for individuals during the last trip to Oštarije.

In August 1941, about 150 Serb internees, including men, women, and children, were transferred from the “Slano” camp to a bay (Furnaža area) near the camp, where they were killed with bayonets in excavated pits. These pits were later mentioned in a report by the Italian health commission, which disinfected the camp. The notorious Ventura on one side, and Sergeant Šljivar with a lamp on the other side of the pit, supervised the execution of the crime. The desolate Pag nights were filled with the sound of women sobbing, wailing, and the children’s screams. The grim faces of the butchers were barely discernible in the meager light of the lamps. “It was horrible,” say the accused, who mostly claim that they camouflaged the killings in the dark. The pits were then hastily covered with earth and stones.

The same morning of August 15th, sixty Ustaša members arrived in the town of Pag with the intention of participating in a large church procession and parade for the Feast of the Assumption – to carry the statue of the Lady from the Old Town Church to Pag. However, the people scattered. The bloody Ustaša apperance provoked horror, disgust, and hatred. Thus, they had to abandon the “parade” willingly or unwillingly. But on their way back, they boasted: “There was blood last night,” they said, “we slaughtered 700 pieces of that Jewish and Serb filth”…

Witnesses recount that around thirty selected Ustaše regularly participated in the massacres, mostly those from Poličnik and Visočane, as well as some Bosnians. The rest had to go only when they stated that they could not do it…Towards the end of August, the camp was to be disbanded. The last transports of detainees were taken to Oštarije and slaughtered in Velebit. The remaining 400 were transferred to Jasenovac where they met the same fate as the others, under the knife and the mallet.

Where is Dunja Polin

According to some statements, only Karlo Heim and Dunja Polin survived the horrors of the Pag camp. As the only eyewitnesses, they were allegedly interviewed in 1946 and 1947 by the District Commission for War Crimes in Rijeka. Besides their names, nothing more is known about them. The record of that interview has not been found. It got lost along with other materials and recordings of the commission related to the “Slano” camp. All efforts to find the material were in vain. Numerous letters testify to the persistent search by the Zadar District Court for the material and the unknown eyewitnesses.

Letters were sent to the Departments of Internal Affairs in Belgrade, Zagreb, Sarajevo, and Osijek, the Jewish Community in Zagreb, Public Prosecutors, the Medical Faculty in Zagreb, and everywhere else it was assumed they could be found. But the answer was consistently negative: unknown, does not reside in this area… In Zagreb, two individuals with the same name (Karlo Heim) were found, but neither of them had been in the “Slano” camp.

Thus, the verdict will be rendered without Karlo Heim and Dunja Polin having the opportunity to face their tormentors.

Report by Dr Stazzi

In late August 1941, the command of the Italian army corps in Kraljevica dispatched a team of 35 soldiers from the medical unit, led by military doctor Dr. Stazzi from Ventimiglia (interned as an anti-fascist before the capitulation), to burn the corpses in the “Slano” camp. In the report of the disinfection commission dated September 22, 1941, submitted to the command regarding the hygienic cleaning and arrangement of cemeteries in Malin and Slana, the following is stated among other things: “Already in the area where the ship anchored, and even more so near the cliffs where we landed, we encountered a very unpleasant stench, characteristic of decaying organic matter. After climbing a path over completely bare terrain, about 400 meters above, we found ourselves in front of a pit 32 meters long, 2 meters wide, and 16 meters deep.

During the journey, we were forced to use gas masks as the stench became unbearable, and the climb forced us to breathe deeply. At a distance of 15 meters, there was another pit, also 15 meters long, equally deep and wide. The surrounding area of these pits was covered with many stones to give the impression of natural terrain configuration. From the mentioned ground, cramped hands emerged, toes, already badly decomposed, and in some places, the clear outlines of human bodies poorly covered with soil. After an additional 400 meters, we descended into another small valley called Karlobaški Malin, which looks towards Karlobag. After traversing approximately 200 meters in a completely rocky zone, without any path, we encountered yet another corridor of earth covered with stones to camouflage the terrain, with the characteristic stench. We began methodical work, removing all stones, and shoveling away the soil layer by layer. Along the entire length of the graveyard, numerous often tied hands, bare and shod feet, heads with faces or necks facing up, etc., became visible.

We have come to the conclusion that the following took place: those designated for burial were bound by their upper limbs in pairs or groups of three (always with electric wire) and placed on a heap of earth above a dug-out pit, into which they then fell, mowed down by machine gun fire. At the moment while death had not yet occurred, the largest stones from the base of the dry walls on both sides of the pit were toppled onto them, pulling the earth down with them, thus the burial was carried out with little effort and quickly. The fact that the wounded were buried alive is evidenced by the disfigured and tragic expressions on the majority of the corpses’ faces. Extracting the corpses was particularly arduous because they were piled without order, huddled and entangled with limbs intertwined and placed in unimaginable positions. In some places, the corpses were found in as many as five layers, one on top of the other, while in other spots fewer, depending on the depth of the pit. In these pits, we only found women and children, while in others, there were mixed men, women, and children. The state of preservation of the corpses varied in different zones because the burials took place at different times, so some corpses could be a month or two old, while others two or three months old. We extracted the corpses using tridents, placed them on improvised stretchers, and transferred them to wooden pyres, where they were abundantly soaked in flammable liquids and burned. About 20 corpses were burned on each pyre.

In this manner, 791 dead bodies were burned, of which 716 at the main cemetery in Malin, 20 in the small graveyard in Karlobaški Malin 2 in the Malin zone, near a spring, one to the right of the shore for docking in Malin, and 52 in the graveyard to the left of the site Slano, which was later shown to us. Among these bodies, 407 are men, 293 women, and 91 children aged 3-14 years. One infant of about 5 months was found. South of the wire fence enclosing the Serb concentration camp, another small graveyard was discovered, where drilling confirmed that the bodies were buried in wooden coffins and quite deeply. Consequently, we did not excavate this site.

The guide who served during the discovery of these zones recounted that the largest number of those deported to “Slana” were thrown into the sea, tied to large stones, and many took their own lives by drowning. The environment in which the deported lived makes it more than likely that suicides were very numerous. For the above works, 70 quintals of wood, 250 kg of petroleum, 550 kg of gasoline, and 45 kg of quicklime were used. The work lasted a total of 10 days and involved 2,720 work hours.”

The attached photographs were unfortunately not found. From this report, only a faint picture of the horrors and atrocities committed in the Pag camps can be discerned. The testimonies of a few eyewitnesses are even more horrifying.

Letter to the “Motherland”

During the war, there was a provincial office for mail censorship in Rijeka, which sent a report to the Rijeka prefect every week with excerpts from letters that were considered interesting. Thus, the report from October 12, 1941, quoted some passages from a letter by Renegat from Pag, Marko Pera Vidolin, who wrote to Captain Vincent Massimo in Mošćenica, among other things, the following:

“Unfortunately, for the second time, we have been abandoned by our motherland, which brings us great sorrow. Firmly convinced that we will be returned under her wing again because with so many massacres committed by these authorities, such a state could not sustain itself. So today, even other people who were Croat sympathisers pray and raise their hands to the sky that this island would be annexed to our motherland. Firstly, because Croatian authorities have left the island, thus the financial situation is poor, and secondly, because since Pag was annexed to Croatia, the authorities have established a concentration camp near Barbat in a desolate place, where they brought Jews and Serbs and massacred them. It is estimated that around 8,000 people were killed and thrown into the sea at the camp here. Additionally, it is said another 15,000 were killed. Moreover, it is rumored that in the interior, the Ustašas massacred and killed the population of entire villages. Due to these sorrowful events, I, as well as the Croatian populace, pray to heaven that Italy takes over this area because we fear that we will also be massacred in a few days.”

I think it is not necessary to specifically emphasise that these crimes were committed at a time when the Italian occupation army was already present on Pag and that the Italians did not make any effort to prevent the mentioned atrocities. Only when almost everything in the camp was massacred, did they decide to burn the bodies and use the “Croat barbarism” (as can be seen) as a means to terrorise the population and “annex them to the motherland…”

Punishment?

And it took a full 11 years for former prisoners to meet by sheer chance at a fair in Benkovac, for Luka Barjašić to stand trial, and for the last veils over the mysterious deaths of the Pag camp inmates to fall. It took a full 12 years for the first culprits to be brought to justice. 12 years! The broken bones and corpses of the unfortunate victims, their wives and children, had long rotted away in the pits of Velebit. The sea currents had carried them from the shallow waters of Pag to unknown marine depths, and the Velebit wind had scattered their ashes over the barren lands of Pag. Above their bodies, the war years had past, offensives had thundered—freedom had dawned! In peace, new springs had blossomed, in peace new snows had swept across Velebit. Peace had calmed the hearts of the people. And seven Ustašas had lived on in peace. In peace?

Is there no nighttime groan and wail from the depths of the Velebit pits, don’t slaughtered children cry out from the barren lands of Pag, don’t frantic mothers scream? Don’t the swollen drowned corpses stare from the dark green depths? Don’t old stains red with blood still remain on the blood-soaked ground, on the clothes and hands of killers? How could one live with murders on their soul, among the graves of victims slaughtered by their own hands, at the scene of the crime? How could one eat, drink, and sleep? These are the questions every normal person who retains a sense of humanity would ask. These were the questions asked by the president of the District Court in Zadar, comrade Josip Carević, after listening to horrific testimonies. The accused did not flinch or have their hair stand on end from these memories, nor did they find anything abnormal in them. They recounted and spoke with ghastly simplicity and a sole aim to “get” as little as possible while concealing as much as they could, hoping to somewhat redeem themselves, to save whatever could be saved with their minimal confessions.

None of the accused admits to more than one murder. Some don’t even admit to that. They all claim they were merely guards and watchmen. They all had to slaughter and kill, but they did it only once, and then they pretended to do their job. They all had to loot, beat with rifle buuts, and drink blood, but they couldn’t. They cried, cursed Baljak Ventura and “Pivac” – Devčić, the bloodthirsty commanders of the camp, hid, feigning stomach pains. One might believe them if the statements were not so contradictory. In that pile of papers, minutes, statements, and confrontations, it’s no longer clear who killed whom and how many were killed. Everything turns red from blood, and the suffering of the innocent human flesh comes to light, horrifying in its stark nakedness.

Luka Barjašić has been sentenced to life imprisonment. The court considered the minor age of the accused and the neglect and influence of the Ustaša commanders. How will the others fare? Probably not better or worse. Despite all the public prosecutor’s appeals and public discontent, the mitigating circumstances remain the same. All the accused were only about 20 years old at the time. I have spoken with many people – ordinary, small folk, as well as comrades in the people’s government, with those who stayed on the sidelines during the struggle, and with those who lost everything dear to them at the hands of the Ustašas. There was no hesitation anywhere. The sense of justice in people’s hearts demanded death! And when people learned that the verdict would likely not be a death sentence, when they heard the reasons for such a judicial decision, they were silent for a while, thought, and nodded. Yes, indeed – perhaps we no longer need that today. And speaking of punishment – I recall Baljak’s answer to the assistant public prosecutor’s question, “How are you, Slavko?” – “Good,” Slavko said. And it was true. Good. They can sleep. The eye of conscience is blind.

Long ago, the emaciated camp prisoners died in the pits, their tortured bones have long since decayed, but we have not forgotten them. They are embedded in the foundations of this country, they are part of our lives, along with the Party and Tito, they represent the peace and independence at our borders.

Maja NARIĆ

Translated by Books of Jeremiah

- Tran. note: Baške Oštarije between Gospić and Karlobag, not the village close to Ogulin called Oštarije. ↩︎

- Tran. note: Orthodox denotes Serbs, majority of whom are Orthodox Christians, although there are Catholics, Muslims, etc. who are Serbs as well. ↩︎

- Tran. note: Many did not make the trek or were killed along the way in the karst pits of the Velebit mountains. Jadovno is the most notorious of these pits and had its own small concentration camp nearby, forming the Gospić-Jadovno-Pag system of camps. ↩︎

- Tran. note: A beach on the northern side of Pag. ↩︎