SERVIA,

YOUNGEST MEMBER OF THE EUROPEAN FAMILY:

OR, A

RESIDENCE IN BELGRADE,

AND

TRAVELS IN THE HIGHLANDS AND WOODLANDS OF THE INTERIOR,

DURING THE YEARS 1843 AND 1844.

BY

ANDREW ARCHIBALD PATON, ESQ.

CHAPTER XX.

Formation of the Servian Monarchy.—Contest between the Latin and Greek Churches.—Stephan Dushan.—A Great Warrior.—Results of his Victories.—Knes Lasar.—Invasion of Amurath.—Battle of Kossovo.—Death of Lasar and Amurath.—Fall of the Servian Monarchy.—General Observations.

Servia and Bosnia were, at this remote period, the debatable territory between the churches of Rome and Constantinople, so divided was opinion at that time even in Servia Proper, where now a Roman Catholic community is not to be found, that two out of the three sons of this prince were inclined to the Latin ritual.

Stephan, the son of Neman,1 ultimately held by the Greek Church, and was crowned by his brother Sava, Greek Archbishop of Servia.2 The Chronicles of Daniel tell that “he was led to the altar, anointed with oil, clad in purple, and the archbishop, placing the crown on his head, cried aloud three times, ‘Long live Stephan the first crowned King and Autocrat3 of Servia,’ on which all the assembled magnates and people cried, ‘nogo lieto!’ (many years!)”

The Servian kingdom was gradually extended under his successors, and attained its climax under Stephan Dushan, surnamed the Powerful, who was, according to all contemporary accounts, of tall stature and a commanding kingly presence. He began his reign in the year 1336,4 and in the course of the four following years, overran nearly the whole of what is now called Turkey in Europe; and having besieged the Emperor Andronicus in Thessalonica, compelled him to cede Albania and Macedonia. Prisrend, in the former province, was selected as the capital; the pompous honorary charges and frivolous ceremonial of the Greek emperors were introduced at his court, and the short-lived national order of the Knights of St. Stephan was instituted by him in 1346.

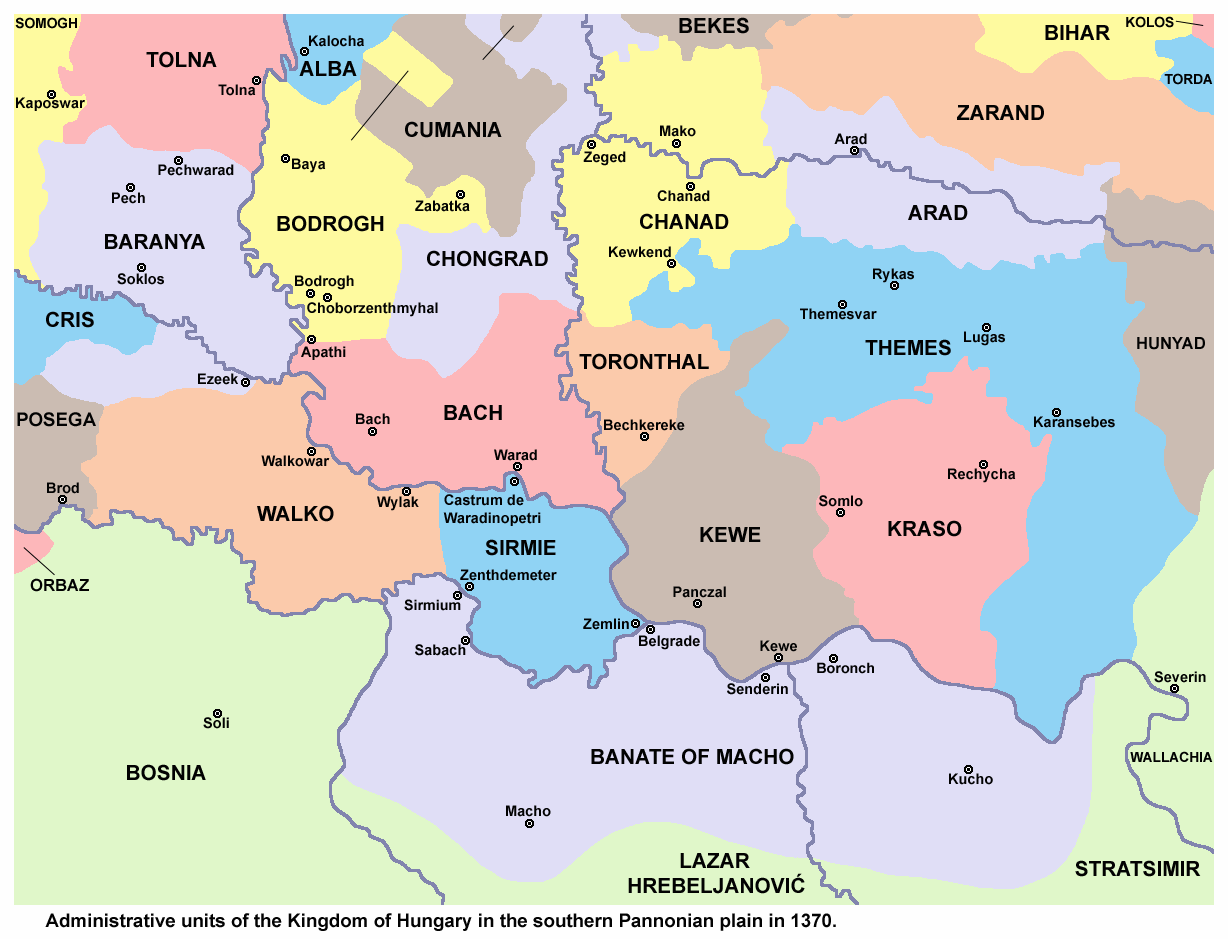

He then turned his arms northwards, and defeated Louis of Hungary in several engagements. He was preparing to invade Thrace, and attempt the conquest of Constantinople, in 1356, with eighty thousand men, but death cut him off in the midst of his career.

The brilliant victories of Stephan Dushan were a misfortune to Christendom. They shattered the Greek empire, the last feeble bulwark of Europe, and paved the way for those ultimate successes of the Asiatic conquerors, which a timely union of strength might have prevented. Stephan Dushan was the little Napoleon of his day; he conquered, but did not consolidate: and his scourging wars were insufficiently balanced by the advantage of the code of laws to which he gave his name.

His son Urosh, being a weak and incapable prince, was murdered by one of the generals of the army, and thus ended the Neman dynasty, after having subsisted 212 years, and produced eight kings and two emperors. The crown now devolved on Knes, or Prince Lasar, a connexion of the house of Neman, who was crowned Czar, but is more generally called Knes Lasar.5 Of all the ancient rulers of the country, his memory is held the dearest by the Servians of the present day. He appears to have been a pious and generous prince, and at the same time to have been a brave but unsuccessful general.

Amurath,6 the Ottoman Sultan, who had already taken all Roumelia, south of the Balkan, now resolved to pass these mountains, and invade Servia Proper; but, to make sure of success, secretly offered the crown to Wuk Brankovich, a Servian chief, as a reward for his treachery to Lasar.

Wuk caught at the bait, and when the armies were in sight of each other, accused Milosh Kobilich, the son-in-law of Lasar, of being a traitor. On the night before the battle, Lasar assembled all the knights and nobles to decide the matter between Wuk and Milosh. Lasar then took a silver cup of wine, handed it over to Milosh, and said, “Take this cup of wine from my hand and drink it.” Milosh drank it, in token of his fidelity, and said, “Now there is no time for disputing. To-morrow I will prove that my accuser is a calumniator, and that I am a faithful subject of my prince and father-in-law.”7

Milosh then embraced the plan of assassinating Amurath in his tent, and taking with him two stout youths, secretly left the Servian camp, and presented himself at the Turkish lines, with his lance reversed, as a sign of desertion. Arrived at the tent of Amurath, he knelt down, and, pretending to kiss the hand of the Sultan, drew forth his dagger, and stabbed him in the body, from which wound Amurath died. Hence the usage of the Ottomans not to permit strangers to approach the Sultan, otherwise than with their arms held by attendants.

The celebrated battle of Kossovo then took place. The wing commanded by Wuk gave way, he being the first to retreat. The division commanded by Lasar held fast for some time, and, at length, yielded to the superior force of the Turks. Lasar himself lost his life in the battle, and thus ended the Servian monarchy on the 15th of June, 1389.

The state of Servia, previous to its subjugation by the Turks, appears to have been strikingly analogous to that of the other feudal monarchies of Europe; the revenue being derived mostly from crown lands, the military service of the nobles being considered an equivalent for the tenure of their possessions. Society consisted of ecclesiastics, nobles, knights, gentlemen, and peasants. A citizen class seldom or never figures on the scene. Its merchants were foreigners, Byzantines, Venetians, or Ragusans, and history speaks of no Bruges or Augsburg in Servia, Bosnia, or Albania.

The religion of the state was that of the oriental church; the secular head of which was not the patriarch of Constantinople; but, as is now the case in Russia, the emperor himself, assisted by a synod, at the head of which was the patriarch of Servia and its dependencies.8

The first article of the code of Stephan Dushan runs thus: “Care must be taken of the Christian religion, the holy churches, the convents, and the ecclesiastics.” And elsewhere, with reference to the Latin heresy, as it was called, “the Orthodox Czar” was bound to use the most vigorous means for its extirpation; those who resisted were to be put to death.

At the death of a noble, his arms belonged by right to the Czar; but his dresses, gold and silver plate, precious stones, and gilt girdles fell to his male children, whom failing, to the daughters. If a noble insulted another noble, he paid a fine; if a gentleman insulted a noble, he was flogged.

The laity were called “dressers in white:” hence one must conclude that light coloured dresses were used by the people, and black by the clergy. Beards were worn and held sacred: plucking the beard of a noble was punished by the loss of the right hand.

Rape was punished with cutting off the nose of the man; the girl received at the same time a third of the man’s fortune, as a compensation. Seduction, if not followed by marriage, was expiated by a pound of gold, if the party were rich; half a pound of gold, if the party were in mediocre circumstances; and cutting off the nose if the party were poor.

If a woman’s husband were absent at the wars, she must wait ten years for his return, or for news of him. If she got sure news of his death, she must wait a year before marrying again. Otherwise a second marriage was considered adultery.

Great protection was afforded to friendly merchants, who were mostly Venetians. All lords of manors were enjoined to give them hospitality, and were responsible for losses sustained by robbery within their jurisdiction. The lessees of the gold and silver mines of Servia, as well as the workmen of the state mint, were also Venetians; and on looking through Professor Shafarik’s collection, I found all the coins closely resembling in die those of Venice. Saint Stephan is seen giving to the king of the day the banner of Servia, in the same way as Saint Mark gives the banner of the republic of Venice to the Doge, as seen on the old coins of that state.9

The process of embalming was carried to high perfection, for the mummy of the canonized Knes Lasar is to be seen to this day.10 I made a pilgrimage some years ago to Vrdnik, a retired monastery in the Frusca Gora, where his mummy is preserved with the most religious care, in the church, exposed to the atmosphere. It is, of course, shrunk, shrivelled, and of a dark brown colour, bedecked with an antique embroidered mantle, said to be the same worn at the battle of Kossovo. The fingers were covered with the most costly rings, no doubt since added.

It appears that the Roman practice of burning the dead, (probably preserved by the Tsinsars, the descendants of the colonists in Macedonia,) was not uncommon, for any village in which such an act took place was subject to fine.

If there be Moslems in secret to this day in Andalusia, and if there were worshippers of Odin and Thor till lately on the shores of the Baltic, may not some secret votaries of Jupiter and Mars have lingered among the recesses of the Balkan, for centuries after Christianity had shed its light over Europe?

The Servian monarchy having terminated more than half a century before the invention of printing, and most of the manuscripts of the period having been destroyed, or dispersed during the long Turkish occupation, very little is known of the literature of this period except the annals of Servia, by Archbishop Daniel, the original manuscript of which is now in the Hiliendar monastery of Mount Athos.11 The language used was the old Slaavic, now a dead language, but used to this day as the vehicle of divine service in all Greco-Slaavic communities from the Adriatic to the utmost confines of Russia, and the parent of all the modern varieties of the Southern and Eastern Slaavic languages.

- King Stefan Nemanjić, called the “First-Crowned” (c.1165-1228), son of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja (1113 or 1114-1199). ↩︎

- “Greek” in this context means “Orthodox”. ↩︎

- “Autocrat” in royal titles means that there is not a higher earthly authority over the ruler. ↩︎

- Stefan Uroš IV Dušan Nemanjić, Paton is wrong in the dates, as he was crowned as King of Serbia in 1331. ↩︎

- Lazar Hrebeljanović (1329-1389), Paton has it backwards here, as he never took the title of Emperor, but being referred to as “Tsar” in epic poetry. ↩︎

- Sultan Murad I (1362-1389). ↩︎

- A few mix-ups here, as it was Vuk Branković who was the son-in-law and it is in folk tradition that he was a traitor. This goes to show that when Paton was writing this (presumably from his notes), there was some mixing of history and folk tradition he would have heard in his travel. ↩︎

- There seems to be some mix-up here, as the Serbian heads of state were not heads of the Serbian Orthodox Church. ↩︎

- Until the discovery of the New World’s precious metals, Serbian mines, particularly silver ones, supplied the majority of bullion for the region and wider European area. During the last years of vassaldom to the Ottomans, the Prince could pay an annual tribute of 11000 gold ducats, while being able to finance and run his own realm. Venice also had at various time in the medieval period offices specifically to deal with the ducat counterfeits which most likely came out of Serbia, as the country provided the bullion for their minting and the counterfeits were of high quality. ↩︎

- A misconception by Paton. Until modern embalming practices were established, Serbs did not practice embalming (it is still not a popular way to treat the remains of a deceased person). This would have been a natural process and a contributing factor to being declared a saint in the Serbian Orthodox Church, as the incorruptibility of remains would be an important factor in the considerations of whether a person should be canonised. ↩︎

- A number of manuscripts that survived in Serbian monasteries were also sold during the early XIX century, most notably by Vuk Karadžić to various libraries or collectors in Central Europe. ↩︎