BY

REV. W. DENTON, M.A.

CHAPTER THE EIGTH.

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE — DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CHURCHES IN SERVIA AND OTHER PARTS OF ORTHODOX CHURCH—DESCRIPTION OF A CHURCH—ALTARS—APSES—ICONOSTASIS—ECCLESIASTICAL TERMS.

Ts only pure examples of Servian church architecture which are to be seen in that country, are the few churches which have survived the devastation made during the conquest by the Turks, and their subsequent occupation of Servia. Of those which remain, scattered as they are, and often owing their preservation to the inaccessible nature of the country where they are situated, my wanderings only led me to the cemetery church of St. Mary, at Semandria, and the monastic churches of Rakowitza, Ravanitza, and Manassia. The town churches are almost all modern, and the village churches which were built during the closing days of Turkish rule, and before the independence of Servia was guaranteed by treaty, are mean, and constructed of the simplest materials. Walls of logs or of hurdles, covered with mud, and roofs of shingle, do not admit of any architectural ornament. The description of the church at Dobra will give the reader a fair idea of this class of churches.

In the towns and some of the larger villages, more ambitious churches of stone, or of brick, covered with plaster, have been erected since the expulsion of the Turks; but these, for the most part, were hastily constructed, to supply a grievous need in the first moment of newly-regained independence; and from one cause or other, the badness of the mortar, or the ignorance of the builders, unaccustomed to construct works of such a magnitude, they already show signs of decay. The walls of the cathedrals of Belgrade and of Schabats, and the large church at Semandria, are all rent with long cracks; and unless the progress of destruction can be arrested, they will, no doubt, before long, fall to the ground.

The types which the architects of these modern churches have imitated are either the Servian churches in the Austrian territories, or the more purely Byzantine churches of Russia. The builders of the Servian churches of Sclavonia, and throughout Hungary; in those villages where the Serbs are settled in any considerable number, adopted the style which was found to prevail in Austria, and were content to make the interior conform to the essential requirements of the Eastern rite. Thus throughout the Servian portions of Austria the churches of the orthodox communion have generally square towers, surmounted by an ungraceful, not to say ugly, spire, swelling out into one, and sometimes two bulbs, painted of a black or chocolate colour; whilst the body of the church is made up of a jumble of classical details—Tuscan pilasters, Corinthian or composite-capped columns, Palladian windows, and anonymous doorways. When the Servians in their own country were able to begin to rebuild their churches, it was natural that in many cases they should be influenced by the style, or absence of style, which they found to prevail amongst their brethren in Sclavonia, and that they should faithfully copy these incongruities. Other portions of the Eastern Church would probably have resorted exclusively to Byzantine models; but then it

must be bore in mind that the Servian Church was never so exclusively oriental as most other parts of the great orthodox Church of the East. The Servian architects of the middle ages, and during the period of the national greatness, were always ready to adopt the details of the architecture of Italy; and especially those which they had seen in Lombardy and the Venetian provinces, with which a considerable literary and artistic intercourse was maintained. Thus, whilst the older churches of Servia are romanesque in outline, and even in some of their principal features—as, for instance, in the exterior arcading of the sanctuary and choir apses—yet the details, such as the windows and the pillars, are often twelfth century in character, and are what one of our own architects would call Early English. The mouldings of the doorways and the capitals of pilasters are often-times of the same character. The traveller will sometimes find in the choir lancet lights with trefoil headings, and in other parts of the building windows with plate tracery, such as may be found in Venetian churches; whilst the frescoes in the interior of these churches are oftentimes of the best age of Italian painting, and executed in the style of Tintoretto, or after the early manner of Raphael.

The canons of criticism, then, which are applicable to churches in other parts of the Eastern communion will require to be considerably modified when we come to speak of Servian architecture. In almost every other portion of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and of the Churches in communion with it, the absence of any external transept is a rule; but in Servia the churches almost always show some trace of the transeptal construction on the outside of the building, and in most of them it is a marked and characteristic feature. Thus, for instance, in the old church of St. Mary, at Semandria, whilst the nave is only 14 feet 6 inches in width, the choir, which is included in the transept, is upwards of 22 feet across. Indeed, except in poor mud-built village churches, the choir is always formed by an addition to the width of the building, making the church, of course, externally cruciform. Again, it is usual, in most other parts of the East, for the prothesis and the disconicon, each of them, to terminate in a small apse, not always externally visible, but almost always so internally: this is very rarely the case in Servia. In the churches of that country the apse of the sanctuary usually embraces the table of prothesis and the diaconicon; and when this is not the case, in place of the recessed wall of these two adjuncts to the

bema being circular on the outside, as is the case in almost all other Eastern churches, the wall on the outside is invariably, and on the inside usually, polygonal. Whilst, again, in most other parts of the Eastern Church the bema or sanctuary is cut off from both the prothesis and diaconicon by internal walls, this is never the case, so far as I have seen, in Servian churches, the whole space behind the iconostasis being undivided. The nearest approach to internal walls of division occur in the church which is at present building in the western suburb of Belgrade. In this instance, the prothesis and diaconicon are so deeply recessed, as to give at first sight the appearance of a wall extending across the bema, but this is only in appearance; and this church, so far as I could judge, in its present incomplete state, has more features of Byzantine architecture and arrangement than occur in any other Servian church.1

Having pointed out some of those specific differences from the other churches of the Eastem communion which are to be found in those of Servia, it may be well to say a few words on the plan and construction of Servian churches in general. In the first place, unlike the Continental Church of Western Europe, the ancient ecclesiastical custom regarding Orientalism is strictly observed throughout the East. The churches are always built due east and west.

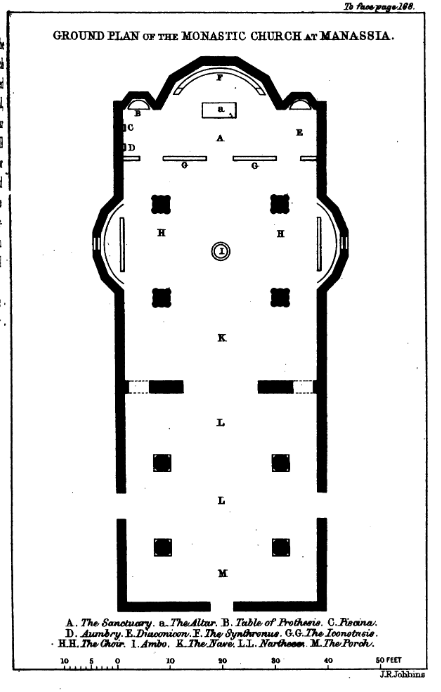

But to come to a description of the several parts of a church, The churches of the Eastem communion are always divided into the sanctuary, the choir, and the nave. These divisions are never wanting. In addition to these essential features, most churches have a narthex, or place west of the nave, in which the women stand during the time of service; and still west of this an internal porch, extending across the whole width of the building. Some, again, have what is called a double narthex, and even a double porch—that is to say, these portions of the church are sometimes divided by pillars, or even by a wall. In the sanctuary, to the north of the altar, is the table of prothesis, on which the sacred elements are prepared for the Holy Communion; and to the west of this the aumbry and the piscina, which latter is always placed in the north wall, and never, as in other parts of the Eastern Church, under the altar. In small churches, the aumbry is occasionally wanting. In the aumbry is placed the chalice and paten, covered with the corporal; here also will be found a singular kind of double flask of glass, made to hold the water and the wine which is required in the Holy Communion. The diaconicon occupies the south side of the sanctuary, and in it are kept the vestments used during the celebration of Divine service, as well as the various office-books of the church. Here will be found the library attached to the church, whenever such exists. The altar occupies the centre of the sanctuary, standing on the chord of the apse, and having sometimes seats behind for the bishop and the officiating priests. Only in one church in Servia—that in the monastery of Manassia—does the old stone bench or synthronus remain.

The altar—for in the Eastern Church there is but one—is sometimes of wood, at other times of stone; or a table of wood is placed on a pedestal of stone; or, again, a stone slab is supported by wooden legs. There appears, in fact, to be no rule in this matter; wood, however, is more commonly used than stone. The altar is always much smaller than with us, and is generally almost square. Thus, for instance, in the church of St. Mary, at Semandria, the altar is three feet nine inches in length, by three feet four inches in width. At the church of the Ascension, in the monastery of Ravanitza, it is three feet eleven inches in length, by two feet eight inches in width; and the altars

in other churches are of similar proportions.

These altars appear small to a person accustomed to the larger ones of the Western Church; but the former are more likely to represent the altars of the early Christians than those which are usually seen either in the Roman Church or amongst ourselves, especially in some new churches. The position of the altar behind the iconostasis at all times prevents more than a portion of it from being visible to the people standing in the nave; and the Eastern Church has thus been saved from the temptation of enlarging the altar to a disproportionate size, in order to obtain effect by increased dimension merely; whilst the well-known constancy with which the Oriental mind adheres to old traditions, and preserves old forms, is tolerably sufficient evidence that the proportions of the altar in the churches of the East are the same as those of the primitive Church.

On the east side of the altar will be found the candlesticks, and generally, but by no means always, a crucifix. In the middle is laid the Evangelium, or book of the Gospels, to be used in the Communion Service, and sometimes a copy of the Eucologion will be found on one side of the altar. With these will often be found the icons or images, usually one of the saint in honour of whom the church is dedicated, and another of our Blessed Lord. But whatever articles of furniture may be wanting, I have invariably found on the altar of every church, whether large or small, a piece of cloth nearly covering the whole top, but, except during Divine service, folded and placed in the centre,

and under the copy of the Gospels. On this is painted the figure of our Blessed Lord resting in the tomb, thus apparently setting the altar before the eye of men as the sepulchre of Christ.

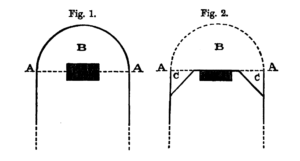

In the churches of Servia the sanctuary invariably ends in an apse, and occasionally it terminates in a central and larger apse, with two small ones on either side, one for the table of prothesis and the other for the diaconicon. But in speaking of an apse, care must be taken not to confound this invariable feature of Eastern churches with what has of late been called by the same name in England; from which, however, it differs essentially. The genuine apse is a semicircle described upon the chord of the are on which the altar stands—a circular extension of the sanctuary; it is not, as so many seem to imagine, the square east end of a church narrowed by an inner circle cutting off the outer angles of the square, and giving a circular form to the chancel. Still less shall we find in the East a rectangular altar placed most incongruously against the circular wall of the sanctuary. Such an arrangement has arisen from a strange confusion of ideas as to the meaning of an apse. The true apse, then, is formed by a semicircle standing on and projecting beyond the extreme cast of the chancel, as in fig. 1, whilst the false apse is made by a semicircle described on the east end of the nave, and usurping the place of the chancel, as in fig. 2—an essential difference, as it seems to me, between the true apse of the East and the make-believe apse of some of our modern churches. A ground-plan will show

the essential difference between an Eastern apse and a rounded chancel. The space B in fig. 1 is the apse of an Eastern church, the circular sweep behind the altar, which stands on the line AA, from which the circle is struck. The English Church, in disusing the apse and in finishing with the line AA, lost nothing of available space for the church. But the now-a-days restorers of apses, in place of giving back to us the space B, always narrow the chancel itself by robbing us of the corners CC, and thus deprive the altar of that dignity which is due to it. This will be evident by a glance at fig. 2. But to return to the description of an Oriental church.

The iconostasis in the Eastern churches takes the place not of the chancel screen, but of the altar rails, It is a wooden partition stretching across the church, and shutting off the sanctuary from the worshippers. It has usually three doorways, though in poor churches one only is sometimes found. These openings have generally a kind of gate reaching halfway up the doorway, and usually a vail. Sometimes, however, a vail without any door is found, and at others a door without any vail. The paintings upon the iconostasis differ in different churches. Usually, however, the figure of the patron saint is placed at the north end, whilst that of the Blessed Virgin occupies the north

side of the central door, and a figure of our Blessed Lord is invariably painted on the south side of the same door. Under the figure of the Blessed Virgin the woman kneels during the service for churching.

On each side of the contral door of the iconostasis, and in the choir, stand two standards of brass or stone for candles, and near these, on the south side, a small sloping desk with two icons, one of which is a painting of the patron saint, or the event from the Gospel history in memory of which the church has been dedicated; the other icon is that of our Blessed Lord. On entering a church for service, or even for the purpose of seeing it, and again on leaving, it is customary to kiss one or both of these images, This is the simple act of reverence which is expected from all. Before the central door of the iconostasis stands the ambo, from which the Gospel and Epistle are read in the Communion Service. In old basilican churches there were usually two, sometimes even three ambos. In the churches throughout Servia there is but one: The ambo in

several parts of the old patriarchate of Ravenna, and again in the Byzantine churches of Sicily, is an important feature. It is a large pulpit or desk raised to nearly the same height as pulpits with us. But in Servia the ambo is a far less ambitious structure. It is nothing more than a small round spot of about four feet in diameter, generally of stone, and usually raised one step above the rest of the floor, though it is sometimes to be found with two, and, in the metropolitical church, with three steps. In old and

in poor churches, however, the ambo is often wanting. It may have been that the ancient ambo was of wood, and of a different form from that now in use, and that this has perished during the time of Turkish occupation. It is, however, remarkable that, in the older churches in Servia, where the ambo is found, it is of wood, and evidently of modern construction, the place for reading the Gospel being marked by a circular stone not raised above the level of the floor.

Immediately in front of the iconostasis is the choir, and in the extremity of the arms of the cross, north and south, are placed the desks for the singers. Sometimes a pulpit projects from the wall of the choir. In the churches where I have seen it, it has been of wood, forming five sides of an octagon, standing on the north side of the choir and reached by steps made in the thickness of the wall. A pulpit, however, is of rare occurrence throughout Servia. In the choir of most churches are seats, one for the bishop of the diocese and another for the prince; in poor churches but one of these will be found, that for the use of the bishop in the course of his visitations. These seats are on the south side of the church, and are generally placed against the wall; but sometimes they occur on the two faces of a pillar, the bishop’s seat in that case being made to look west, and the prince’s seat being placed at right angles with that of the bishop, and looking northward. West of the choir is situated the nave, which is often undistinguished architecturally from the choir. In some churches in Servia the floor of the nave is sunk one step below the choir, whilst the narthex rises again to

the choir level. Round this part of the church are ranged miserere stalls for those who are unable, from age or infirmity, to stand without some support during the long services of the Greek ritual; but in some of the more ancient churches—as, for instance, in the monastic church of Ravanitza—there still remains the stone bench which formerly, in all churches, ran round the narthex and porch. West of the nave stands the narthex, which in primitive times was the place assigned to penitents, but is now occupied by women; and beyond this is one and sometimes two porches. In the south-west angle of the porch, or if there be no porch to the church in the same angle of the narthex, is placed the font, which is sometimes of copper or other metal, but more commonly of stone; and behind the pillar which is nearest to the place where the font stands, will be found a table, and upon it the register-book for baptisms. The porch and narthex is sometimes covered by a gallery running across the whole width of the church, and called a narthex gallery. Here was formerly the place for the women, but it is now seldom used, except as in churches in Sclavonia, for a school or sometimes as a convenient receptacle for lumber.

Those churches which were built during the time when the Turks occupied the country were necessarily made without any place for bells, which were forbidden to the Christians; but when this interdict was removed, and freedom of religious worship was insured by the independence of the country, a framework of timber, two or three stages high, was usually erected near the west end of the church in which to hang the bells, In churches, however, built since the deliverance of the country from the Turkish yoke, the belfry is in the tower, over the west door of entrance.2

For the sake of students of ecclesiastical antiquity, I add the Servian names of several parts of the church and its furniture, and the vestments of the clergy. The names were kindly written in my note-book by the parish priest at Topschidere.

Oltar—the whole space within the sanctuary; the place of the altar.

Prestol—the altar.

Gertwenik—the table of prothesis.

Ouchiwallick—the piscina.

Zawvyesse—the vail before the doorway of the iconostasia.

Pewnitza—the seats for the choir.

Phekonostasse—the small table in the nave on which the icons stand.

Krstalnitea—the font.

Mouska preprata—the space in a church between the iconostasis and narthex ; the choir and nave of a church.

Genska preprata—place for women; the narthex.

Kadionitea—the censer.

Odyeyanie—vestments.

Epitrahil—stole for priests.

Phelon—chasuble.

Naroukwitze—the maniple.

Poyasse—the girdle.

Stirhar—the stockerion or alb.

- Auth. note: See the plan at page 168. [previous chapter] ↩︎

- Auth. note: What I have endeavoured to describe in this chapter will be more fully understood by a reference to the plan of the church of Manassia, with the various portions of the building distinguished from each other. ↩︎