BY

REV. W. DENTON, M.A.

CHAPTER THE SEVENTH.

FROM POSHERAWATZ TO SEMANDRIA—NJERESNIZA—VILLAGE INN—MOUNTAIN TORRENTS—POSHERAWATZ—TRADE OF TOWN—SCHOOLS—AGRICULTURE—SEMANDRIA—CEMETERY CHURCH—FORTRESS—CROSS OF GEORGE BRANKOVITCH — TURKISH GUARDHOUSE — SERVIAN INK.

Next morning, after breakfast, we set out on our road through Posherawatz to Semandria, in order to rejoin our steamboat and return to Belgrade.

At first, our way lay through a narrow valley, part of which we had traversed in our excursion to Granpek the day before. After driving through the fields a couple of miles, we turned our ponies’ heads westward, and our journey, for the first ten or twelve miles, was through a country of the same character as we had passed in our way from Milanowatz to Maidanpek. Our route was along the tops of a succession of moderately lofty mountains, their slopes on either side being clothed with oak and beech, plane and ash, and here and there an elm—a tree, however, rare in these forests, The monotony of this was broken by an occasional glade, with a thread of water running down the side of the mountain and breaking the silence of the woods with its musical flow. From the detached character of the high ground over which we passed, our road was a succession of abrupt ascents and descents, and these our ponies seemed to think were especially intended to be galloped over. So long as we were on smooth ground, the pace of these animals was respectable, not to say at times slow; but no sooner did we come to a sharp descent, with a piece of rough ground

and a fall of some twenty or thirty feet, down which the least mistake on their part would hurl us, than they broke into a furious gallop, and, swinging us from one side of the waggon to the other, to the grievous discomfort of our ribs, carried us in triumph to the top of the next ascent.

On our road, in the early part of the day, we passed groups of wine and salt merchants returning from yesterday’s market at Maidanpek, and camps of gipsies scattered here and there through the woods, with their ponies tethered wherever an opening in the forest gave sufficient pasturage for their beasts. In several places these people had constructed little huts of green boughs to shelter themselves from the heat of the sun; and wreaths of blue curling smoke from the fires, round which the women were busied in preparing the morning meal, pointed out their encampments. After ten or twelve miles of mountain travel, our road for nearly the same distance ran through the middle of a valley swarming with peasants ploughing and harrowing their fields, or employed in watching their cattle, which the scarcity of hedges makes no light task.

A more busy scone than that which the whole valley of the Pek, and indeed the land on the border of any of the rivers of Servia, presents during the months of spring, can scarcely be imagined. Whilst the men were ploughing, the women sowed the seed, and at the same time trampled it into the earth after the plough. The large number of oxen—oftentimes as many as ten or twelve yoked to each plough—and the children assembled in groups under the shade of the nearest tree, playing in sight of their parents, and the hammocks or Wallach cradles suspended to the branches of the trees, gave variety and animation to the scene. After about four hours’ drive, we drew up our waggons at an inn-door in the little village of Njeresniza, inhabited by a mixed population of Wallachians and Servians.

The little tavern, or restaurant, consisted of two rooms on the ground floor, with a loft or sleeping apartment above for the family of the tavern-keeper. One of these rooms was open to the road, and on a board viands of all kinds were spread to tempt the hungry passenger. Not that the food in these taverns ever had this effect on me. Perhaps it was that I was never hungry enough during my travels to overcome the repugnance which I felt to the look of a lamb about the size of a large cat roasted whole, and at joints of miniature mutton cold and dry, heaped upon coarse saucers on shelves near tho window. These dishes and a few bottles of raki or slivovitza—a

kind of plum brandy—the national and very favourite drink, proclaimed the calling of the owner of the establishment. In other parts of the room were piles of water-bottles, a stove for charcoal, and an oven. A large fireplace projected some dozen feet from the wall, and occupied more than a fourth of what was a good-sized room. In fact, the fireplace was in the middle of the room, and ready for the use of any customer who might require a fire. Where the smoke escaped, I could not ascertain. The floor of this

apartment was of earth, and pigs and a brood of chickens, marshalled by an old hen, roamed under the long tables, from which no doubt they picked up a good livelihood.

Though on the whole the room was as unlike any apartment to be found in a country inn in England as could well be, one custom of trade identified the inn of Servia with that of England, and testified to their relationship to each other. Behind the door of the inn at Njeresniza were scores of chalk as voluminous as any that can be seen in England, the Sorvian inn-keeper evidently thinking with old Gervase Markham, that “there is more trust in an honest score, chaulkt on a trencher, than in a cunning written scrowle, how well soever painted on tho best parchment.” Beyond this door was the second apartment, used not only as a dining-room, but also as a sleeping apartment, at least during the day. For this purpose a fourth of the room was raised about two feet from the ground, and was reserved for a hard, but no doubt welcome place of

rest to the drovers and peasants, almost the only persons who had occasion to make use of this inn.

These litte taverns appear to be much frequented. Indeed, out of five houses, which, with their outbuildings, stables, and sheds for cattle, make up the whole of the little square in the centre of this village, three are inns of the same description as that at which we baited our ponies and refreshed ourselves, having brought supply of food from Maidanpek for this purpose.

Near this inn stands an old and picturesque Turkish house, now used for a draper’s shop, and stocked with an abundant and varied assortment of goods. A little beyond this is a mall Wallachian church of the same kind as that which I had seen at Dobra. The only peculiarity which I noticed in this church was, that instead of a copy of the Gospels merely, the whole New Testament lay upon the altar. Beyond this church, and at some distance down the village, stands the Servian church.

After resting for upwards of an hour, during which most of our party sheltered themselves from the heat of the sun under the far-projecting eaves of the inn, we resumed our journey for Posherawats, where we hoped to find a resting-place for the night. For a while we kept along the banks of the Pek, here a very shallow and inconsiderable stream, but with a channel admitting a large volume of water, which no doubt rolled between its banks during the winter months, but especially after the melting of the snow on the high grounds during the spring. After about half an hour’s drive through the valley our road ascended, and wound round bold projecting bluffs of limestone and over hills covered with lilac-trees in full blossom; whilst far below us here and there we could see an eagle hovering along the banks of the river, and sweeping down upon its prey. The road was sometimes one of difficulty, as the hillsides were channeled with the dry beds of mountain torrents, which in their resistless course had in several places swept away the road itself. One of these torrents had laid bare what on examination proved to be a bed of very fine cement; and it is to be hoped that the revelations which these channels make of the wealth which is at present hidden, may compensate for some of the mischief done every year by these mountain streams. It is the prevalence of these mountain .torrents, and the force with which they rush downwards to the valleys, which renders road-keeping so difficult in Servia. Rain such as falls upon the heights, when collected into a rivulet, soon destroys the labour of months, and renders it necessary to tunnel the roads repeatedly, and to span the water-

courses with small arches, which when completed may perhaps be never required. The hills on both sides of this valley are gradually being brought under cultivation, and on the top of those immediately adjacent to the river were fields of maize stubble, the remains of last year’s harvest, now lying fallow, in preparation for the next year’s sowing, alternating with brown patches of recently-ploughed earth. As soon as we had descended from this ridge we passed through a rich and fertile country, the lower grounds being mostly in pasture, and the slopes of the hills green with the young foliage of the vineyards. For miles our route lay across what might have been mistaken for a park in England, but over roads which told us unmistakably that we were in a country as yet only half cultivated. Night closed round us whilst we were yet at some

distance from our resting-place, and it was not until half-past nine o’clock that we caught sight of the lamps in Posherawatz, and fully ten before we had found our way to the inn. Our journey had lasted fourteen hours, including nearly two hours for rest, and we had driven at least sixty miles over the roughest of all roads without any change of ponies, and yet when we drove into the inn-yard our beasts seemed still unexhausted.

Like most of the towns and large villages in the interior of Servia, Posherawatz resembles an encampment of hucksters at country fair, where the booths have been in some way made permanent without any improvement in their external appearance. With the exception of a few houses in the environs, white-fronted, with green verandahs and venetian blinds, each standing in the midst of a small garden gay with flowers, the whole town consists of streets of shops of one story, standing some ten or twelve feet high; the dining and sleeping apartments being situated on, the ground, and in the rear of the shop.

Nothing could exceed the animation and bustle which reigned in all parts of the town as we walked through it in the morning. Our inn, which was almost the only house with rooms above the ground-floor, was situated in the centre of the town ; and long before five o’clock in the morning the noise in the streets made sleeping impossible, notwithstanding the fatigues of the previous day. Immediately opposite the front of our inn was the fountain, from which all the streets of the town seemed to radiate. This fountain is painted red, blue, and white, the colours of the national flag, and surmounted with a cross. In the shops of the town it would be hard to say what might not be bought. In addition to those of the butchers and grocers were shops filled to the roof with bales of cotton and bars of iron from Turkey; others with drags and medicines to prolong life; and others, again, where tombstones might be purchased, with a space in which to record the powerlessness of all medicine to sustain life. Here were heaped together confectionary and comfita, crockery and coarse earthenware, clay balls for washing, good soap, and scented oils, mingled with Dutch clocks, and all kinds of tin work and hardware; some shops seemed entirely occupied with a counter covered with heaps of Turkish tobacco ; others were filled with casks of wine and beer, with the spigot invitingly ready, and large glass jars of raki and slivovitza for those who loved these stimulants; whilst other shops, again, were filled

with hosiery and all sorts of drapery hanging at the doors, or temptingly displayed, with a skill which English shopkeepers would not disdain. In fact, there seemed to be every article which was ever enumerated in the tariff of any nation, or that can be found in the list of goods in the commercial dictionary of Mr. Maccolough. The whole town appeared to swarm with customers. The country round Posherawats very well populated, and the peasants and cottagers along the lines of road are for many miles dependent upon this town for the supply of the goods which they need. In one shop, with an unmistakably Hebrew name over the door, were traders bargaining for kid skins, for which the owner asked a sum equivalent to five francs apiece, but for which we were told he would probably be willing to take half a dozen piastres. In another

were peasant girls seated at the door, and trying on the variegated stockings which are fashionable throughout Servia; whilst in another we saw some pretty gipsy girls cheapening artificial flowers, and blushing very perceptibly through their bronzed checks at being detected in the act. A more animated scene than that which the town presented at six o’clock in the morning, or one which proclaimed the great prosperity of the neighbourhood, can scarcely be imagined. Interested in the bustle around us, we slowly sauntered through the streets, examining the various articles exposed for sale, attracting quite as much attention from others as we ourselves bestowed on the novel spectacle. As we walked through the crowd, one of the bystanders, more acute than the rest of his fellows, or perhaps more travelled, detected our nationality, and to show the extent of his knowledge of our language, saluted us in very good English, and proudly wished us “Good night” at six o’clock in the morning.

There are two churches in this town—one at the entry of Posherawatz from Njeresniza, and the other in the heart of the town; the former is a large building, of no particular ecclesiastical character, having a tower at the west end, surmounted by the usual chocolate-coloured bulbous spire. It is of the same date as most of the

other large churches of the country, having been built within the last ten years. The town is also well supplied with schools, and at eight o’clock in the morning, through the streets in the outskirts of the town, many a group of boys and girls might be seen toiling slowly along, with satchel on their backs or a strap full of books dangling from their arms, and often with lesson-book open in their hands from which they were endeavouring to learn the last column of spelling as they walked to school.

Attracted by the sound of a Gregorian chant, which proceeded from one of these schools; I went in, and found a room full of pupils learning the multiplication table, and aiding their memory by singing the “twice two are four” to one of the ecclesiastical tones. This schoolhouse consists of two rooms for the scholars, which are separated by a central hall. In one of these rooms hung a tolerable painting of St. Sava, the national saint of Servia; and here the pupils, left to themselves, were employed in learning their arithmetic. In the other room I found the master engaged with a class of boys, who were repeating the catechism. On my entry, one of the boys stole out unbidden,

and soon returned with a chair, which he placed for me. I waited whilst the master examined the pupils—at first the class collectively, and then separately—in the catechism, which they were able not only to repeat fluently, but which they seemed to understand. After this had been finished, another class was examined from a book of geography. This lesson mainly consisted in an enumeration of the chief cities of the various countries of Europe and Asia, with, in most cases, the name of the river on which those cities are situated. In compliment to myself, I presume, the first question asked was the name of the capital of England, and the river on which it is built. The most perfect order reigned, not only in the schoolroom in which the master was seated, but also in that in which the scholars were employed in learning their tasks. The supply of books and slates, of black-boards and maps, appeared very ample, and the rudimentary books in use, so far as I could judge, seemed very good.

What chiefly struck me, however, in this and in other schools which I visited, was the mixture of the children of different classes or grades in society. As there is, properly speaking, but one class in Servia, the distinction which is created by wealth or by the possession of landed property is very trifling, and is practically almost disregarded. Many of the school-children at Posherawatz were barefooted, whilst others were evidently of a class that regarded shoes as a necessity, if not of life, yet at least of its social status. The courtesy, however, which is so remarkable a characteristic of all classes in Servia, whatever their worldly wealth may be, rendered it difficult to distinguish the child of a peasant from one of the richer class of society.

After a breakfast of coffee, with plenty of new milk, and cakes of hot bread, we set out for Semandria, which we reached after a drive of about two hours. The country between Posherawats and the Morava, which we crossed in our journey, resembled English rural scenery in the neighbourhood of the mansion of a large landed proprietor, where the trimness of the park seems to extend to and influence the cottages of the labourers. The road, however, on the east bank of the river was of the same primitive and chaotic character as that of which we had‘ such woeful experience the day before. No sooner, however, had we crossed the river by the ferry-boat than we came upon the great road leading from Semandria to the frontier of Turkey, which is as good as the majority of roads in England. In contrast to that over which we travelled yesterday, we pronounced it excellent.

Our route now was through what may still be called forest land, but where the forest has already, in a great measure, disappeared, and where the cultivated lands are daily encroaching upon the domain of timber. The scene is exactly similar to that which is found in the neighbourhood of a new settlement in North America. Belts of wood, with patches of cultivated lands, in which the stumps of the trees still remain though charred and decaying, and in time to be worked into the ground as vegetable mould or manure. Between these stumps Indian com is planted, and the abundance of good land renders it unnecessary to economise the ground, which is under this partial

cultivation. Agriculture, indeed, is in a rude state throughout Servia. The population is far from being so dense as to make it at all necessary to cultivate the land with care. The field which has been under crop one year, is suffered to lie fallow during the next, and the maize stubble is then sufficiently rotten to be ploughed into the ground, which in this way recovers itself without the aid of manure. The fields, again, for the most part, are very foul with weeds, and spurge and charlock seem oftentimes to be the only crops, In the neighbourhood of the large towns, more care is bestowed upon the ground than in the remote interior; yet even there the agriculture is of the rudest description.

Round Belgrade maize and pumpkins are sown together in the fields, and the whole process of ploughing, harrowing, and sowing, is of the simplest kind. After the strip of ground, which has been lying fallow during the past year, has been ploughed, and the maize stubble fairly covered, the seed is immediately sown. The wife or the daughter of the peasant follows the plough with an apron full of the mixed seed, which she drops alternately into the furrow, and at the same time covers and tramples it down with her bare feet. As soon as a strip of ground three or four yards in breadth has been thus ploughed and planted, the light simple plough is unfastened from the pole, and a harrow of bushes, weighted with clods of earth, like our common bush harrow, is drawn over the field, and this is all that is needed until the plants of maize are high enough to require hoeing. At harvest time the heads of corn are cut off, leaving some two or three feet of stubble in the ground to rot, and in the second spring to be

ploughed in as before. The pumpkins come to maturity long before the corn, and cutting these and hoeing the maize plants go on at the same time. Sometimes, in clearing fresh ground, it is found easier to bum down the trunks of the trees than to remove them by means of the axe, and then to grub up the roots. When this is imperfectly done, the charred trunks often remain in several parts of the field, rising from the midst of the crop of maize or wheat which occupies the site of the old forest. On one such blackened trunk of a once magnificent oak-tree, which we passed in our morning drive from Posherawatz, we saw a noble eagle perched and at rest, whilst three others floated in different parts of the horizon. In the course of our drive we often saw two, or sometimes three eagles at one time, but this was the only occasion when we saw more than three of these monarchs of the rocks and woods at one and the same moment.

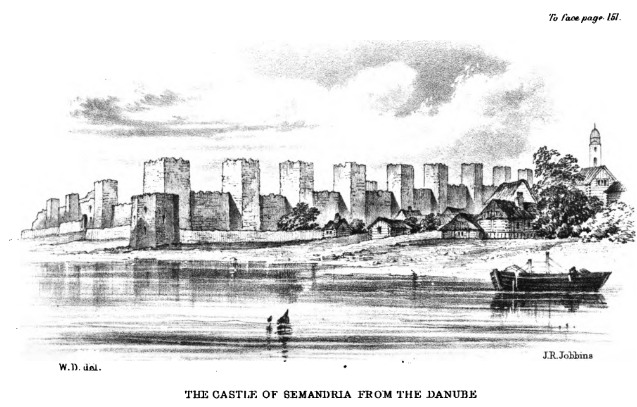

As we approached Semandria and the borders of the Danube, the country grew more hilly, till, as we topped the last ridge which overlooks the town, we obtained a beautiful view of the river, flowing, as though in the calmness of conscious power, past the old Servian fortress of Semandria, which, with its strange coronet of towers, juts out into, and was intended to command, the Danube. The slopes of all the hills, in the neighbourhood of this town, are covered with vineyards, which appear to be very carefully tended. The wine made at this place is by, many considered the strongest and best of all the Servian wines.

The environs of Semandria are prettier, the cottages more commodious, and the little patches of garden-ground better laid out, than: in the outskirts of any other town which I have seen in Servia. The situation of the town, also, is one full of picturesque beauty, situated as it is at the foot of a range of hills some of which overhang and command it on the south and west. Unlike most other towns, there are sufficient objects of interest in and about Semandria to give it considerable attractions. The ancient chapel of St Mary, in the cemetery, is probably the oldest ecclesiastical building remaining in Servia The old fortress, built by George Brankovitch in the fifteenth century, is the largest and most remarkable piece of military architecture to be found in the country. Semandria itself abounds in old Turkish houses, with their gardens

bounded by high walls, over which rise the mulberry and the fig tree; whilst the modem church of St. George is by far the finest of all the new churches in Servia.

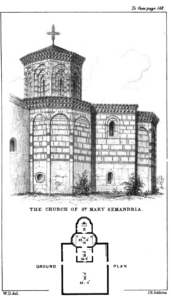

On one of the spurs of the range of hills, which, like a half moon, rise to the west and south of the town, is situated the cemetery, surrounding the little church of St Mary. The situation of the church under a high bank, which rises immediately to the west, and the fact that the floor is some six or seven feet below the surface of the ground on the outside, favour the tradition that for a long time it was covered by earth, and its existence unknown to the Turks. To this, perhaps, may be owing its complete state of preservation, and the unmutilated character of the interior. With the exception of the usual dints of pistol bullets defacing the frescoed head of our Blessed Lord, which

fills up the whole of the ceiling of the polygonal lantern in the centre of the building, there are no marks of violence noticeable. The church, consisting of sanctuary, nave, and choir, is only thirty-eight feet long. The apse, as well as the extremity of the transept, are polygonal in the exterior, though circular in the interior. ‘The altar consists of a table of wood, probably modern, standing on three antique carved stone pillars. The rood surmounting the iconostasis presents this singular feature, that it is turned away from the people, and faces the east end of the church. There is no ambo, but the place of it seems to be marked with a round stone, though I am not sure that this is not accidental. In front of the iconostasis are two stone pillars for candles, and the candles, which are of wax, covered with sheet iron, each six inches in diameter, and about twelve feet high, being the largest candles which I have ever seen. The choir is separated from the nave by a solid wall built up to the roof of the building, and pierced by a doorway for the worshippers in the nave; the wall forming a support to the polygonal dome, which supplies almost the whole of the light to the building. The

walls within the church are covered with old frescoes, some in a tolerable state of preservation.

Externally, the church is very interesting. The outline is cruciform; the north, south, and east arms of the cross terminating in an apse, which is, as I have just said, circular in the’ interior, and polygonal on the outside, These apses are arcaded; the whole exterior wall, from the roof to within four feet of the ground, including the apses, being constructed of stone, with thin red brick in horizontal and vertical lines of rusticated work. An octagonal lantern of similar work, but more highly decorated than the wall, rises from the intersection of the nave and transepts. Each face of the octagon is recessed with arcading down to a long narrow light in the contre. Both the wall and

the lantern terminate in a bold cornice, with three lines of brick corbels.

In order to adapt this church to modem requirements, and to ft it for the use of the population living to the west of the town, a large square room has been added, without attempt at ornament, or any endeavour to make it accord with the rest of the church. This new part is used as the nave and narthex, and contains stalls and a font From the western door a view of the church may be obtained by those who are standing in the new portion, and a narrow light on each side enables those near the aperture to join in the service.

On the other side of the town, and just outside of the fortress, stands the church of St. George, a modern building, erected only about seven years ago. It is a

fine and characteristic specimen of modern Byzantine work, and is surmounted by six domes, one of which is over the western entrance. A. good effect is obtained by some beautiful foliage running round the windows and along the lines of the building. On examination, this turned out to be metal-work, covered with plaster. Unfortunately, such work has no durability, and the plaster has cracked and peeled off in several parts of the building. Inside the church the most noticeable feature is the pavement of the nave, sunk one step both below the choir and the narthex. In the diaconicon is a good library of Church books, together with a greater number of theological works—chiefly the writings of the Fathers of the Eastern Church—than I have seen elsewhere. It is not, I imagine, a mere coincidence that the width of the church is the same as the length of the nave (41 feet 7 inches), and that the choir and sanctuary are respectively of the same length (21 feet 6 inches). In front of the church, and outside the inclosure, stands a simple but effective wooden cross, about twelve feet in height.

But the moat conspicuous object, and one which strikes the eye of the traveller as soon as he comes within sight of this city, is the old Servian fortress, which stretches out into the river. This is the most perfect specimen of military architecture existing in the country. It consists of a row of tall square towers connected by curtain, neither tower nor curtain possessing rampart, battlements, nor embrasures of any kind, and seemingly only calculated for passive resistance. Both inside and outside of the walls is a ditch, which lends some additional security to the fortress. It is now occupied by a Turkish garrison, being one of the seven strong places reserved by the great Powers of Europe to the Sultan. A little in advance of the main gateway, which, indeed, is the only one accessible from the land side, a little outwork, with a wall loopholed for musketry, is the only piece of offensive work that I could see in the whole structure.

The walls of this fortress testify to the abundance of the Roman remains which existed in Servia at the date of the Turkish invasion. The towers and other parts of the walls are full of fragments of sculpture and inscriptions of the lower empire, the former possessing, probably, little artistic value, though the fragmentary inscriptions might settle many a matter of history at present doubtful, or help to unsettle what is now accepted for fact by historical students. One of the towers of the fortress, however, furnishes such an instance of foresight in its builder, that it will excuse a few words of description. Built at a time when the arms of the Turks, everywhere victorious, were pressing northward, and threatening to subjugate a great part of Europe, and when the conquest of Servia must have appeared imminent, the builder of this remarkable fortress, in the course of its construction, inserted into the stone wall of a tower which stands in the very centre of the citadel a cross of red brick, of some twelve feet in height, running through the thickness of the wall, and consequently irremovable, except by the destruction of the whole building. Round the cross are the sacred monograms, and underneath an inscription in old Servian, all worked into the wall, and made of the same material, red brick. The mark for nearly four centuries for Turkish bullets, which have liberally battered both brick and stone, the cross stands out all the redder for the violence which hatred for the emblem has instigated. It met the eyes of the successful invaders at their entry, it has survived the assaults of rage and cruelty which has marked the times of the Turkish occupation, and it will doubtless be the Iast object which the Turkish garrison will see as it withdraws from the fortress. In various parts of the walls, in inaccessible heights, or in angles of the towers, smaller crosses have been here and there inserted; but this cross, which overlooks the whole garrison, and stands alone, like the banner around which a host is to

rally, is one of the most remarkable trophies which the forethought and devotion of man has ever reared.

Outside of the fortress, the ditch which runs round the walls can at any time be filled from the river, but in the inside, the ditch is kept full of water, stagnant and stinking, covered with a vegetable coating of yellow and green weed, and looking the very haunt of fever. It must be very destructive to the health of the troops, who, to the number of six hundred, live in mud tumble-down cottages in the inside. These form a little town, as each house is surrounded, in proper oriental style, with a garden jealously fenced in and concealed from the eyes of all except its owner. On one side of the gate of the fortress is a dilapidated mosque, rising, as is frequently the case, over a little sutler’s shop, or canteen, where sherbet, tobacco, and sweetmeats, are spread out to tempt soldiers and the children of the garrison.

On the opposite side of the gateway is situated the guard-house. In front of this is ranged a number of muskets of every age and shape, and in various stages of uselesness. I naturally imagined that this, on a small scale, was like the armoury in the Tower of London—an exhibition, or museum of artillery; but to my astonishment, I learnt that these were the arms of the guard, placed here for daily use. How the ammunition can be served out for these heterogeneous muskets, and whether, in case of need, these fire-arms will not be found more dangerous to the possessors than to their foes, are matters for the consideration of the Turkish authorities. Without loopholes, however, to the walls, and in the absence of ramparts, it can matter little what firearms are placed in the hands of the defenders of such a fortress. But, indeed, the place itself, apart from the want of sufficient arms for the garrison, is utterly untenable. Within a mile it is commanded at various points from the hills, which overlook both town and fortress, and a few shells dropped into the midst of the clay huts, and setting fire to the shingle and thatch of the roofs, would force the garrison to a speedy surrender, At the first moment of any real warfare, this, and other garrisons in Servia, must be immediately abandoned by their present holders. They are maintained during peace at a useless, and in the state of Turkish finances, at an enormous cost, and in time of war will have to be deserted.

When I visited this fortress, I met the son of Achir Pasha, the Turkish commander at Belgrade. He appeared an intelligent lad, of some eighteen or nineteen years old, and was dressed in modern Turkish fashion—that is to say, in a style that was completely Frankish. He was then on a visit of inspection to this fortress, to prepare it against any step which the Servians might take in a moment of exasperation, at the bombardment of Belgrade, which had at that time been determined upon.

At my entry into the guard-house, I was invited to a seat on the divan, and complimented duly on being Ingleski, and, therefore, a thick-and-thin friend of the Turk. Delicious coffee and a paper cigarette were handed to me, the former of which I accepted, but, as I did not smoke, declined the tobacco. The conflict between the new and old fashions—they are not ideas, for these survive outward fashions—was very noticeable in the place. On one side of me was the son of the Pasha, who, with his attendants, sat forlorn and uncomfortable-looking in their ill-made and, upon an oriental, certainly most ungraceful Frankish dress; and on the other side the commander of the garrison, Turk of the old school, in the flowing graceful robes which, to our minds, is inseparable from the notion of a Turk. The Pasha’s son, again, was puffing away at a cigarette in the style of a lounger about Paris, whilst the old Turk on my right was soothing himself with the long chibouque.

I slept at a small and—smallness apart—very comfortable inn in Semandria. Everything in my little room was clean and neat, like what would be found in a village inn in England. Supper was served up to us—my Servian friend and myself—in my own apartment. Besides the bed, table, chair, and German stove, the only furniture of the apartment consisted of a few pictures, one or two of which were of some antiquity. On the walls hung a small old panel-painting of our Blessed Lord; another of the head of St. John the Baptist in a charger; a large and showy one of St. Nicholas, a popular saint in Servia; together with these was a small carved and painted diptich of the Virgin and Child, and the Archangel St. Michael—a fair amount of religions paintings for a small bedroom in a small inn. Next morning, after an abundant breakfast, we took the steamboat for Belgrade,