BY

REV. W. DENTON, M.A.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH.

SCENERY OF THE DANUBE—IRON GATES—COAL MINE—VILLAGE CEMETERIES—DOBRA—WALLACHIAN CHURCH —MILANOWATZ—GIPSIES—FOREST ROAD—MAIDANPEK—IRON WORKS—MARKET—GRANPEK—COTTAGE—TAVERN.

Fwe greater contrasts are to be met with than that which is presented by the scenery of the Servian and the Hungarian banks of the Danube. The latter, for the greater part of the way from Belgrade to the entrance of the Iron Gates of the Danube, is perfectly flat, very fertile, and pleasing to the eye, but altogether of a quiet pastoral character. The Servian shore of the Danube, on the other hand, runs along the foot of a succession of hills, mostly well wooded at their summits, and having their slopes well cultivated or covered with flocks of sheep and goats, but bold and picturesque, with quiet villages shadowed by lofty forest trees, and hanging to the sides of the hills or nestling in the gorges which run towards the interior. Here and there the scenery is diversified by the ruins of an old Servian fortress of the days of the Empire, or by a modem church dating from yesterday, and the time of freedom from Turkish domination. The steamboat, in its course toward the mouth of the river, passes on the one side in front of bold cliffs, with a fertile strip of land at the foot, oftentimes resembling the Undercliff in the Isle of Wight; and on the other a line of long low islands, covered with fragrant shrubs, in which the only sign of life is a small Austrian guardhouse, or the encampment of half a dozen wood-cutters.

From Bazias, a little above the western entry to the so-called Iron Gates of the Danube, the scenery undergoes a change, Near that place the range of the Carpathians crosses the river, which has broken itself a course and now flows through a ravine formed during some convulsion of nature. Here the scenery on both sides is of the most romantic character, and the wildness and stern sublimity of the precipices on both banks of the stream have given to this part of the country the name of the Iron Gates. It is a portal of rock, through which the river flows, over ledges which in some places are barely covered with water. Bold bluffs of marble and of the hardest limestone run down into the water, whilst gigantic crags of porphyry, twisted into the most fantastic shapes and tinted with every colour of the rainbow, are seen in wavy bands or zigzag moulding, regular as though the workmanship of man, but on a scale utterly beyond the power of human hands to rival Masses of many hundred feet

in length present the fantastic appearance of an enormous agate, scored over with lines of faultless regularity which to counterfeit even whilst they mock the art of the engraver.

These walls of living rock were festooned with honeysuckles and clematis, and covered with miles of lilac-trees in full blossom. The hills which tower above these rocks are covered to the summit with forest trees of the greatest height, mostly oaks and beech, ash and plane; whilst wherever a margin of earth is interposed between the precipices and the river, the water’s edge is fringed with rows of “pendulous” birch and willow. To make the green of this enormous sweep of forest more vivid, there is dotted here and there the wild plum and cherry, the pear and the apple; which in April were covered with blossoms of snowy whiteness. In the midst of this profusion of verdure gleamed in small patches of light, as the sun fell upon its bosom, what was in reality one of the greatest of European rivers, but what it was very difficult for us to believe to be otherwise than a broad and land-locked lake, so completely was every outlet hidden from our sight by the winding of the river banks. Within the “iron gates” the water is very shallow, and rushes in all directions in a multitude of tiny rapids over ledges of rock, which at all times, but more especially in the midst of summer, when the water is low, require great care and a perfect local knowledge to enable the pilot of a vessel to steer through. The western entrance of these gates is made more than usually picturesque, by a thin needle of rock standing some dozen feet above the surface of the water in the very middle of the channel.

A few miles below the entry to “the iron gates,” our steamboat was moored for the night near the little village of Dobra, as some of the company were desirous of examining the coal mine which had recently been discovered near this place. .

In the cool of the twilight we set out for a scramble through the forests and over the hills to the mouth of the mine, which was some three miles from the place where our vessel had been moored. For more than a mile our way lay along the banks of the river, by the huts of Wallachian herdsmen and the farmsteads of Servian yeomen; over little rustic bridges, through meadows fragrant with newly-cut hay, and stubble-fields bristling with the yellow stalks of maize; past troops of children swinging under the gnarled boughs of gigantic ash-trees, and labourers returning from the fields with their tools slung across their shoulders, or more frequently carried in the hands of their wives and daughters. It required some effort of the mind to enable us to be sure that we were nearly three thousand miles from home, and that the pastoral scenes were not those of our own country, but that we were really in Servia and amongst a Sclavonic people.

After walking nearly an hour, we came to the mine which had been—not sunk into—but driven about twenty yards into the mountain side. The works were of the most primitive description; and the coal, which lay in heaps round the mouth, had all been taken from or near the surface, and had been dug out without knowledge of the proper way of managing a mine. One of our company, however, who was a coal viewer from the banks of the Tyne, having brought down a large heavy compact mass, where the French overseer had hitherto only obtained dust, pronounced the coal to be of the finest quality, equal to that of Newcastle. As we were leaving, our miner, happening to notice the heap of rubbish accumulated round the mouth of the workings, was led to examine some of the earth more narrowly, and discovered that the seams of coal were mingled with fire-clay of a superior kind; and from what he saw that evening, confirmed by a more careful examination next morning, he was convinced that nothing but skill and enterprise were wanting to render these workings most valuable to the material wealth of the country, and most important to the navigation of the Danube.

Our way back to the steamboat was made over the shoulder of the mountain, instead of along its foot, our road leading us past large folds of sheep guarded by vigilant watch-dogs, and across the track of abundance of hares whom we startled by our intrusion, and down narrow pathways thick with the shade of forest trees, with their branches hung with sweet-scented shrubs, until we again reached the river. After supper, I paced the deck until midnight, listening to the song of countless nightingales. So still, indeed, was the night, and so pure is the atmosphere in these parts, that ordinary sounds can be heard to a-great distance. Thus we could readily distinguish the call of one bird on the Hungarian bank of the river replied to by another on the Servian side. Tho nightingales, however, were not without their rivals. The frogs, which abounded in the little pools along the border of the river, and in the meadows by its side, made the night vocal, not with their croak, but with their gable; for the noise which is made by the frogs along this part of the Danube resembles the cry of a flock of infuriated geese rather than the genuine croak of a frog of Western Europe.

Next morning, whilst others of our party were engaged in examining the commercial capabilities of the neighbourhood, and were making an excursion to see some other coal works on the opposite side of the mountain to that which I had visited on the evening before, I strolled to the village of Dobra, about a mile and a half to the west of the place where our boat had been moored for the night.

The way to the village led past two small cemeteries, one apparently deserted, and both of them at least half a mile from any houses. The little village cemeteries of Servia are less squalid and forlorn-looking than similar ones in France and Germany, but they lack the neat appearance and the shade and repose of an English churchyard. The entrance lies through what is known in England by the name of a Iych-gate. Such gates, however, as with us are only seen at the entrance of a churchyard, are in Servia common not only to cemeteries, but also to private houses: the piece of shingle roofing being absolutely necessary for the protection of the wood-work of the gate from the effect of the sun. In the centre of the first cemetery which I entered stands a square piece of cob-wall with a shingle roof, but whether tool-house or chapel it was impossible to determine. Ono or two dry twigs stuck at the head of some of the grass evidenced an attempt at planting a tree, which seemed to have failed from want of water. The tombstones were of very singular forms, but scarcely any could be met with older than the time of the War of Independence.1 Over the little mounds of earth and in and out of the graves sported large green lizards, besides troops of small brown ones. In no place are so many lizards found as in these cemeteries; the dry hillocks of earth which rise over the graves, and the uninterrupted quiet which reigns around, makes the abodes of the dead a favourite retreat for these beautiful beings. Eastern fables represent the spirit of man under the shape of a lizard; and the reason for so doing seemed clear enough, as I looked on the number of these reptiles sporting around the graves, or lying basking in the rays of the sun on the top of a tombstone.

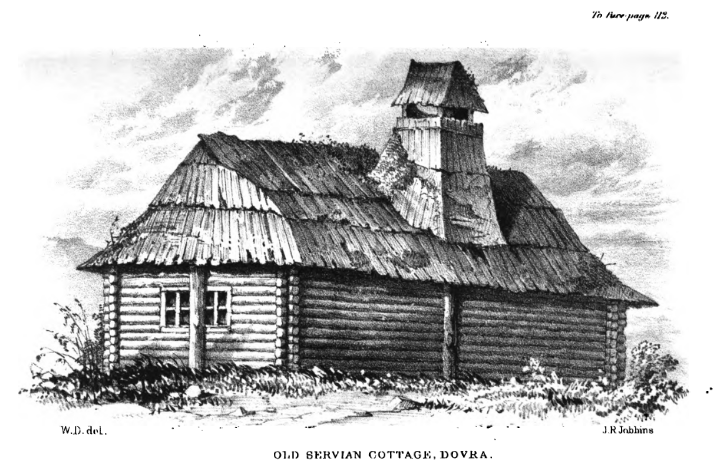

About half a mile beyond the cemetery the village commences. Like most country villages in Servia, it is surrounded by a palisade of stakes, some eight or ten feet high, stuck into the earth, and bound together at the top by a piece of wattle-work. This manner of enclosing a field or village is common throughout the country. The fence is made to prevent the cattle from straying during the night, as well, perhaps, as to guard against the prowling of a wolf or bear, which, when driven by hunger, has sometimes been known to carry off sheep or cattle. Most of the cottages in the village are of the old Servian type, walls of logs, or of wattle, daubed over with mud and covered by a roof of oak shingle, with an enormously disproportioned chimney of the same material. The roof almost always projects on one side, so as to make a kind of open apartment, similar to tho loggia which is found in a Turkish house, where, however, it is raised one story from the ground. Under this shelving roof, but in the open air, the members of the family assemble during the summer months, for their meals, surrounded by tubs, iron pots, and other wooden ware, which, equally with human beings, require to be protected from the rays of the sun. Here and there, however, throughout this Village, neater and more convenient, though less picturesque cottages, of a type which, for want of a more appropriate name, may be called European, have been erected within the last few years, and others are now being built.

It is a satisfactory evidence of the progress of the nation in material prosperity, and also a proof of the security which is now everywhere felt in Servia, that in every village through which I passed during my excursion in this country, from the banks of the Danube on the north to the Turkish frontier on the south, and from Schabats on the west to Milanowatz2 on the east, I found houses which had but just been erected, and almost invariably others in the course of being built; and these were always houses roomier and of a more comfortable and more durable kind than the cottages which they have replaced, or amongst which they are being constructed.

The village of Dobra is divided by the channel of a little sluggish river which, in the summer and autumn months, finds its way to the Danube by half a dozen small streamlets of a few inches in depth. The breadth of the channel, however, and the quantity of pebbles brought down in its course from the mountains, are sufficient proofs of the respectability of the stream during the winter and spring months, when the volume of its waters is increased by the torrents from the hills and the melting of the snows in the interior. It was then, at a little distance from its mouth, a small and placid rill flowing through meadows alive with herds of cat, shut in at one time by a gorge grey with lava and sombre with masses of basalt, over which flocks of goats were ranging in quest of food, which seemed to be regarded as sweeter because of the difficulty experienced in finding it; at another time widening into a valley, with a farmstead and mill perched on the slope of the hills, and shadowed by clumps of enormous trees.

In the village, the pebbly bed of the river was covered with long slips of new linen bleaching in the sun; and whilst this slow and silent process was going on, groups of women and young girls were congregated to watch over their property, and to enjoy that gossip which, whether in a little village in Servia, or in a fashionable drawing-room in Mayfair, makes up a great part of the occupation of life. At this time of year, and in all parts of Servia, when the women are not wholly employed in the more laborious works of agriculture, the beds of the half-dried streams are almost always sure to present this scene. As the girls walk to their daily task in the fields, and the peasant woman plods along by the side of her husband to share in his labours, their hands are usually filled with the distaff. In the winter time, when the rigour of the season prevents all field labours, they are to be found busy at their simple looms; and in the bright warm days of spring, as of old —

“Maids and matrons,

On the banks their yarn and linen bleaching,”

meet for companionship and gossip.

The little Wallachian church at this place is so exact a counterpart of the village church in the rural districts where this people are settled, that a brief description of one will serve for that of all the other Wallachian churches which the traveller will find in the interior of Servia. It is built in the midst of the cottages of the village, and but for its detached belfry, and the absence of any litter of domestic furniture within the enclosure in which it stands, would scarcely be distinguished from them. The church is thirty-two feet in length by twenty-one in width, external measurement, without including the apse at the east end. The floor is of mud; the roof is of the same kind of oak-

shingle as that which covers all the cottages of the village, and open in the inside. As the church was erected before bells wore allowed to be used by the Christians of Servia, a detached belfry of woodwork in frame has been erected since the church was built. This stands in the little churchyard and at the south-west corner of the church. Near the east end of the church are one or two tombs of former priests, and at the head of the last made grave is a wooden cross, Beyond these graves, of course no others are to be found, as all other bodies are buried in the cemeteries outside the village. The churchyard is fenced in with the same kind of palisade as that which is placed round the village.

The interior of this church is in keeping with the poverty of the exterior. It is divided into sanctuary, nave, and narthex; the choir is not architecturally distinguished. A simple slab of wood, resting on a block of the same material, serves for an altar. A small and common table is the only furniture within the diaconicon. The table of prothesis is rather better, and the piscina, which is of stone, is placed on the ground by its side. Two dirty tin candlesticks, with tapers about the size of children’s Christmas candles, stood upon the altar; and the priest’s vestments, the veil of the iconostasis, and the covering of the altar, were all of cheap printed calico. Two stone columns, serving for candlesticks, a little in advance of the sanctuary, a seat of painted deal for the bishop whenever he may chance to visit the church, and a desk for the icons, were the only articles of furniture in the nave. The church is dedicated in honour of St. Nicholas, and his image occurs twice on the iconostasis, which, in addition to the usual paintings, is decorated with cheap prints, daubed with the commonest colours.

During the evening our vessel dropped down to Milanowatz, through the same kind of scenery which I have already attempted to describe at the beginning of this chapter. The town, which is thrown back a little from the banks of the river, is approached by a pretty pathway fringed with pollarded willows. It is a very pretty and thriving place, and is built with greater regularity than most of the other small towns of the country. The remains of the earthworks with which it was defended during the war of independence may still be traced round a great part of the town.

‘After dinner we were visited by a party of gipsies, who sang several of the national airs and popular songs of Servia, especially the piece of music which is a favourite with all classes in this country, the “March of Prince Milosh.” The gipsies are a very numerous body in Servia; they are met with in all parts of the country; and the energetic part which they took during the war with Turkey, and the services which they rendered to the national cause, have tended to give them a higher position here than in most other countries of Europe. They are mostly members of the Greek Church, frequenting the churches like the other inhabitants of the country, and are altogether of more settled habits than gipsies in general, though they are still reckoned a class apart from either the Wallachians or Servians, and are especially excluded from the suffrage. On the borders of Turkey many of the gipsy bands profess the Mahomedan faith. These people are the charcoal burners, the tinkers and smiths, the basket-makers, and trinket vendors, as well as the musicians of Servia. In the winter months they collect in the towns, but in the summer-time they resort to more congenial haunts, and are chiefly to be found in the recesses of the forests. The dress of this people, but more especially that of the women, is almost identical with that which, from the paintings in the tombs of Thebes, we know to have been the dress of the people of old Egypt, by many presumed to have been the native place of the gipsies. The head-dress, especially, bears the closest resemblance to that which is found in the paintings from Egypt preserved in the British Museum. In complexion they are as dark as the Hindoos or Nubians, and finer bronze figures than the naked gipsy children can nowhere be seen. In summertime, and when they are in their home in the woods, not the children only, but the adults also, throw off the cumbersome and useless garb of civilised life, and roam about completely naked—wonderful models. for the painter or the sculptor.

Next morning early we set out for a journey across the mountains to Maidanpek, the seat of some extensive copper and iron works. Our carriages consisted of three

waggons about seven feet long, which were little more than a light framework of wood set upon wheels, without springs. A bundle of hay at either end, over which were

placed our rugs and the scanty bedding that we might require, furnished us with seats, which an occasional halt for the purpose of shaking up made fairly endurable. Our

drivers were Wallachians, dressed in long linen tunics and drawers of the same material; a deep leathern girdle, ornamented with thongs dyed of various colours, was bound round their waist; a pair of leggings and shoes, made of thin strips of leather, curiously fastened together, protected their feet; and a small round felt hat, in which was jauntily stuck a peacock’s feather, covered their heads, and completed their simple costume.

For upwards of an hour we were employed in climbing the side of the hill which overhangs Milanowatz. Although not much more than two thousand feet above the level of the river which we were leaving, yet the winding nature of the road and the steepness of the ascent, even with all the advantage of the zigzags by which we reached the top, took our ponies more than an hour to place us on the summit. For a short distance the way was a tolerably smooth one, but for the most part our road could only be compared to the piece of rough ground which is sometimes seen at the entrance to a ploughed field, where the clay soil is cut up by innumerable wheels of all dimensions, and the ruts have been afterwards baked hard by the sun. As the wagons jolted over these roads in posse, which, however, were certainly in no sense of the word, roads in esse, it was with difficulty that we could keep our seats by clinging to the side of the waggons. When, however, we had reached the summit, we soon forgot all this discomfort in the beauty of the scenery.

At our feet gleamed in the morning sun the Danube, flowing in countless eddies as the river rushed over the various ledges of rock which stretch across the bed of the stream, every one of these eddies being distinctly visible even from the distance at which we were. Across the river we saw first the graceful swell of the mountains on the left bank, and then beyond these the bolder and more rugged outline of the whole Carpathian range in its sweep through Hungary. On the Servian side of our road we had a billowy sea of hills, not a range of mountains, but a chaos of conical hills covered with gigantic trees. Occasionally from the height over which we were passing, we looked down upon little plateaux of cleared and cultivated grounds, upon fields of Indian com, and folds of sheep; but for the most part of the journey we had no trace of man, and when we lost sight of the river, as our road turned to the south, we made our way through a primeval forest. From the dense nature of these woods, the trees generally rise with straight and tall trunks, and majestic oaks and beeches with a stem of a hundred and twenty feet may be seen on all sides. We counted five varieties

of the oak by the roadside. The banks, which sloped from our path, were covered with the usual weeds and flowers, spurge in great profusion, violets, pansies, harebells, speedwell, and the common flowers of our English fields. The else unbroken green of the forest was pleasingly diversified by the snowy blossoms of the various wild fruit-troes, All this profusion of timber-trees, however, is but of little value in a country which has no outlet for its trade. Every one therefore makes use of this timber as he needs it, and the largest trees are sacrificed for the commonest object. The finest oaks are cut down for a stockade for the field, for shingles for the roofs of cottages and outhouses, or for fuel for the fire, Any passenger who needs a walking-stick may cut down a tree for the purpose, and the little consideration which is bestowed upon all this lavish profusion of nature may be gathered from the common proverb, “Whatever is scarce in Servia, wood and water are within everybody’s reach.” The best practical comment on this proverb is presented by the number of dry and blackened trunks of trees everywhere seen in these forests, which have been destroyed by the fires of the gipsies or swineherds.

This part of the country was well known to the Romans during their occupation of Servia, and here are situated the mines which wore worked by them, and, until a recent period, have remained untouched and almost forgotten since their time. The intricate mountainous character of this comer of Servia, and its boundless forest fastnesses, made it the chief retreat of the patriot bands during the War of Independence against the Turks It is a country in which a handful of resolute men might stay the march of an army.

On the plateaux of the smaller hills we saw spots of cleared land, surrounding small farmsteads and cottages; but with these rare exceptions, the only inhabitants of these interminable forests are the game, which is abundant, and the countless herds of pigs, which run wild and find ample food under the oak and beech trees. During our journey of some five and twenty miles, we met the mounted postman with his mail of letters, and two or three labourers returning to their noontide meal; beyond these we saw no human being. After a journey of five or six hours, we came to a scene that instantly riveted our attention, but one to which no description can do justice.

Our wagons were drawn up by the road-side, where, on a sudden break in the mass of dense forest, a beautiful glade was interposed. A slope of some twenty acres of the smoothest turf, and of the most perfect park-like aspect, facing the south, broke the monotony of our forest journey. Around on all sides was the same dense wood, through which we had been passing; but here the edges of this piece of natural park were decorated with wild fruit-trees in full blossom, planted with as much regularity as though by the hand of man. Tufts of the Spanish broom, clumps of fragrant May, and blackthorn were mingled with these trees, and completed the fringe of white blossoms which surrounded the glade. The thread of snow which ran round and seemed to keep back the mass of forest-trees which pressed on all sides round the sward, brought out more vividly the green of the oaks and beeches in their fresh spring verdure. In the centre of the glade a magnificent wild pear-tree reared its head, covered, like the rest of the fruit-trees of the forest, with white blossoms. Beyond and on all sides stretched hundreds of conical hills in wild confusion, completely covered with stately timber-trees ; and in the horizon three ranges of hills of various shades of purple, each range perfectly distinct, bounded the view to tho south; whilst to the right of our course, a wall of living rock, bare of all vegetation, shut in the scene in that direction. Two eagles sailing through the air, and hovering over the forest in quest of prey, completed the picture.

Late in the afternoon we reached Maidanpek, situated, on the banks of small stream which winds through a narrow gorge, with sufficient room at the bottom for two rows of houses. The cottages, for the labourers, the offices, and the extensive sheds, furnaces, and foundries, were erected at the expense of the Servian Government about five and twenty years ago. The iron mines had been long known: indeed, they had been worked in the time of the Romans, and now, after some centuries of disuse, these works have been resumed. The construction of the necessary furnaces, smelting-houses, and forges, were undertaken by an Austrian contractor, and the expense to which the Government was put was enormous. This great outlay, and the non-remunerative character of the establishment, led the present prince to arrange with a company of French capitalists for the future working of the mines upon condition of paying a royalty to the Servian Government. With this was coupled certain concessions, as to the navigation of the Danube between the different ports of Servia, and the exclusive rights to the seams of coal which exist in various parts of the mountains between Milanowatz and Njeresniza.3 The Englishmen whom I met and accompanied on the journey from Belgrade to Maidanpek, and from thence to Semandria,4 were the representatives of a company of English merchants, to whom the French company proposed to make over so much of their concession as related to the navigation of the Danube, and the working of the coal-mines near Dobra. The party consisted of a well-known merchant of London, a civil engineer, and a coal-viewer from the banks of the Tyne; and their report of the capabilities of the country and its commercial prospects, which is now before me, is only a confirmation of what I imagine every one, with the use of his eyes, will arrive at as to the riches of Servia, both agricultural and mineral.

‘The village of Maidanpek consists of a double row of houses, about half a mile in length. In the centre a large piece of land has been reserved for a market. One side of this is occupied by the storehouses of the company, with a colonnade running along the front. On another side stands a neat brick church, with a framework of timber, and a little bell-turret at the west end, of a very German appearance; and adjoining this the village school, with a couple of taverns, being, as it seemed, respectively houses of call, one for French and Servian, and the other for Wallachian travellers and labourers, Another side of the marketplace is bounded by small neat cottages, and on the fourth the only boundary is the hill which towers over the village. One end of the Government store-house is set apart for the worship of the French Roman Catholics, the officers and employés of the company ; and two or three of the superior houses in the village are tenanted by an officer of the Engineers, by a captain of Artillery, and by another agent of the Servian Government, whose duty is to examine the cannon-shot and other military stores which are made at this place.

As Saturday evening closed in, the marketplace began to be occupied by wine carriers and salt merchants, by traders in leather and com, by flour-factors, and sellers of butter, cheese, cream, and other dairy produce, who had arrived overnight in order to be in readiness for the market on Sunday morning. As we walked through this place late on the Saturday evening, we found the owners of the various articles of merchandise stretched on the ground, with their heads resting on bags of camel’s hair, fast asleep, and their horses tethered by their side. Next morning, by daybreak, the business of the market commenced, and the sale of goods was nearly over before it was suspended during the morning mass. The Sunday service on that occasion was, I am sure, such as had never before been witnessed in the valley of the Pek. Within a circle of a hundred yards might have been heard the Sclavonic ritual of the Eastern Church, the Latin mass of a part of Westem Europe, and the English service of the Church of “the farther West.”

After our own service was over, we had a short drive through this romantic valley, past rocks which the Romans had torn down in their search for iron, and in front of mines which, in the time of the Servian empire of Stephen Dushan, had been worked with great success, and then had remained sealed up, and all but forgotten, during the ages of Turkish oppression and misrule, until the present age of freedom and of hope for Servia. The short rule of Kara Alexander5 appears to have been honourably distinguished for the activity with which every scheme for the improvement of the country was pushed forward. Well-planned roads were then made, bridges constructed, schools built in every village and town, fresh churches erected, and several monasteries restored.

Nor were the arts of peace alone regarded, though these appeared to have received the chief attention of the Government. The freedom which Servia has acquired at the expense of so much suffering can only be maintained by the possession of means to defend it. In order to restrain that freedom, and to shackle the newly acquired independence as much as possible, the Government of Turkey stipulated that no military stores should be introduced into the country. The discovery, however, of mines of sulphur, the existence of abundance of saltpetre, and the boundless forests teeming with materials for charcoal, have rendered Servia independent of supplies of gunpowder from foreign countries; and her own mines of iron, and the mechanical skill of her sons, have made the importation of military stores unnecessary. At this village the whole processes of casting and polishing cannon-shot, of making shells and fixing the fusees to the carcases, are carried on under the superintendence of officers of the Servian army, select number of whom are sent every year to Liege, or to the other military foundries of Europe, for instruction in this branch of their profession. About a couple of miles from the village of Maidanpek, passing through meadows already knee-deep in gross and yellow with marsh marigolds, and crossing half a dozen times the little tortuous stream which runs through the valley in which it is situated, we came to the small village of Granpek, formerly a more considerable

village than Maidanpek. Like many other places, however, it has changed with the times, being now greatly surpassed by its noisy and busy neighbour. One short street, of mud hovels, roofed with shingles, with here and there a cleaner and more commodious cottage of brick and plaster, each, however, with a little strip of garden ground, comprises the whole village. Its inhabitants, for the most part, are Wallachians, employed as Iabourers at the adjoining iron and copper works, or earning their bread as carriers and drivers, As we passed through the village, we saw groups of women gathered for friendly gossip, their infants slung over their backs, or lying on the ground at their feet, whilst the elder children were paddling in the water. However intermingled the Servian and Wallachian women may be, and however much they may resemble each other in their dress, they may always be distinguished by the way in which they carry their children. A small tub of thin wood, a little thicker than that which is used by us for hat-boxes, and very much the size and shape of an ordinary foot-bath, with the exception of having a curve to fit the back, is used as the cradle of the Wallachian infant. There, slung over the shoulders of the mother, it slumbers through the journey which the parent makes, or, laid on the ground, reposes whilst the mother is engaged

in field-work. The Servian peasant, on the contrary, carries her child slung over her back in a neat hammock of camel’s hair, or of coarse canvas. During the spring and summer months, whilst there is work to be done in the fields, the traveller will generally see some of these cradles hanging by the branches of the trees, or fastened to poles in the middle of the field, and covered with green boughs; the children who are old enough to be released from the cradle, and too young for the yillage school, sprawling on: the ground, or playing round the cradles of the younger children.

Throughout Servia the love of finery in the peasant women shows itself in the display of coins, either in the shape of a necklace, or bound round the head. These treasures are handed down from mother to daughter, and reach back even beyond the traditions of the people, In these necklaces may be found coins of ancient Macedon, of the old Greek colonies of Asia, of Byzantium, long before it was known to Constantine, mingled with money of the lower Empire, of Venice, of Ragusa, and of the Servian princes, kneses, despots, or emperors. The smallest children, even though in other respects naked, are decorated with treasures which a numismatist might envy. In one cradle into which I peeped, the sleeping infant of some six weeks old was adorned with half a dozen smooth coins fastened round its unconscious head.

In our saunter through Granpek, we looked into one of the cottages, and was courteously invited by the peasant woman who resided there to enter. The cottage consisted of two rooms, one used as a kitchen, the other as a sitting and bed room. A shed adjoining the cottage was filled with wood and garden tools, and at the end of a small kitchen garden, fringed with bright flowers, stood a little framework summer-house, raised some twenty feet from the ground, and giving a view of the whole valley. The small kitchen was almost entirely filled with the fire-place, which projected half across the room, and was so contrived as to enable the person engaged in cooking to do so without going in front of the fire. The sitting-room was scrupulously clean, with a polished oak floor; guiltless of any covering. On the walls were a couple of beautifully

ornamented pistols, a musket, and a yataghan; and in one of the comers of the room hung pictures of St. Nicholas, the Blessed Virgin and Child, and a couple of Scripture prints, with a small silver lamp in front. The most conspicuous decorations of the room, however, in addition to a large bouquet of flowers on the table, consisted of the handsome black and red coverlet to the beds. As we were looking round the room, a little boy, about six years of age, came in, and after taking off his little red cap, took our hands and kissed them. This is the usual salutation which all children give to their elders. On a sidetable in the cottage were three piles of books, a Servian Bible printed at Belgrade, school-books, an almanack, two or three religious biographies, a short abstract of history, and a collection of Servian songs. Of all these I made mental note in the absence of the woman, who, leaving the room as soon as we had entered it, shortly after returned with a tray of wine and light bread. It would be impossible to find greater personal and house cleanliness in any place than we found here, or more courtesy, unmingled with anything like fawning and servility. We had stumbled into this cottage by accident, but we were told, what more extended experience confirmed, that it was an average specimen of the cottage of a Servian peasant. The cottages of the Wallachs are more dingy, and not so neat as those of the Servians ; but even these are by no means dirty.

On our return to Maidanpek, we met at dinner the Greek priest, the captain of Artillery (who has the over sight of the shot and shell foundry), the village prefect, and one or two of the mining officials; the Roman Catholic priest was unfortunately unwell, and unable to join us. Whilst we were at dinner, which was more French than Servian, a band of the zingali assembled under the windows of our dining-room, and sang the usual national songs, which were now familiar to us, In the afternoon, as we crossed the village green, in which the market was held in the morning, we had found it alive with a long line of dancers; and in the evening after dinner as we went to the church, which the Greek priest kindly opened for us, we passed the Servian and Wallachian taverns, which were both filled with men and women, actively employed in the same exercise. In the former of these, the first thing which met our eyes was the floral decoration of the walls, the centre being filled with the English word “ Welcome,” worked in green leaves. I need not say that this spontaneous act of courtesy was done in.compliment to ourselves. Indeed, in whatever part of Servia we chanced to be, the hospitality and welcome given us by all classes was very gratifying, and the more so as when I left England the newspapers had begun to print paragraphs of mysterious origin, telling the world that Servia was “profoundly agitated” —that it was a country dangerous to travellers, but especially so to “Austrians and English.” So far/however, from the truth were all these paragraphs, that it is impossible to imagine a country freer from agitation, or one in which the English traveller could receive a heartier welcome; and this is the more noteworthy, since the treatment which the Servians have received from the Austrian and English Governments is as unjust as it is ungenerous and short-sighted.

No power on earth can prevent the death of the Mahomedan power in Turkey, nor long delay the complete independence of the Christian races, who have acquired from adversity strength of character and firmness of will to fit them for prosperity and to enable them to rule. Apart from the injustice which marks our relations with the Servians and Bulgarians, it is surely impolitic to store the minds of these young and vigorous aspirants for national existence with the memory of long-continued wrongs and bitter sufferings, which we have aggravated by the support held out at all times to the oppressor. It is well to remember this, because at no moment since the days of Mahomet himself is the fanaticism of the Turks so unrestrained as at the present day, and consequently the sufferings of the Christians so great.

But to quit politics, and to return to the merry-makers at the taverns,

In the Servian tavern, mingled with the peasants, were several French and Germans employed in the mines and foundries; and above the roar of all other voices we heard that of a tall, sinister-looking, but good-tempered giant, the French overseer, who was singing, in strong patois and with appropriate gesticulation, the terrible Marseillaise. As he threw his whole soul into the words which he was singing, he appeared transformed from a quiet plodding miner into an infuriated sans culotte, and I seemed to

see before me the model which De la Roche, and our own Ward, have transferred to their canvas—a mad patriot of the days of Robespierre; and I understood better why this song has been interdicted by governments desirous of leading the French nation into the ways of peaceful improvement and internal quiet.

The dances of which whilst in Servia I was at different times a spectator consisted of long lines or circles of dancers—never of pairs nor of small groups; and I noted that the dancers amongst the Servians, as I have mentioned before, held each other by the girdle. The Wallachians, on the other hand, were linked together, each dancer holding to the shoulder of the next but one to him; so that the whole mass of living beings was, as it were, chained together by links crossing each other. Again, the dances of the former people, though fatiguing, were less so than those of the Wallachians. These latter, men and women, locked together indiscriminately, stamped and sang, shouted and perspired, like a company of furies. In the midst of all this madness, however, everything was governed by good temper. There was an absence of all quarrelling; and though the wine had evidently been strong enough to inflame, I saw nothing like intoxication.

After passing these taverns, we accompanied the Greek priest to his church, which he kindly showed us, and answered the questions which we put to him about the services. Like most of the priests in Servia, he spoke German, Hungarian, and Wallachian; but, what is not so universal amongst the parish-priests, he added to this very fluent Latin.