UDC: 94(497.11 Belgrade)“1690“(093.2):355.48

Tatjana KATIĆ

Abstract: Abdullah bin Ibrahim nicknamed Üsküdarî was a participant in the military campaign of grand vizier Mustafa Pasha Köprülü against Serbia in 1690. In his diary, he described one of the largest destructions in the long history of the Belgrade fortress. In October 1690 during the Ottoman bombardment of Belgrade, which was then in hands of the Habsburg Monarchy, one grenade struck a large powder storeroom and caused an explosion that destroyed the medieval castle of despot Stefan Lazarević. The castle, built in the early 15th century, was situated in the present-day area between the Victor monument and the Ottoman fountain at Defterdar’s Gate, where today only a miniature scale model reveals its former appearance. Üsküdarî’s dramatic first-hand description of the explosion and of the slaughter of defenders in the Danube port tells not only about the human and material costs but also provides information on the location of some of the city’s buildings and neighbourhoods.

Keywords: Ottoman Empire, Habsburg Monarchy, Great Turkish War (1683—1699), Serbia, Ottoman chronicle Süleymanname, Abdullah b. Ibrahim el-Üsküdarî, siege of Belgrade.

A military and civic settlement on the hill above the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers has experienced many cycles of building, destruction and rebuilding in its two-thousand-year long and tumultuous history. Today’s fortress, for the most part, originated in the first half of the 15th century. From 1404 to 1427, during the rule of despot Stefan Lazarević, two new fortifications were built along with the restoration of old ones; those were the Upper Town on the plateau on top of the hill and the Lower Town at the Sava and Danube riversides. An old 12th century Byzantine castle situated in the west corner of the plateau was thoroughly reconstructed and enlarged with a dungeon tower and other buildings. It became a fortified castle of despot Stefan and the last defensive stronghold within the fortress. Also, two new ports were constructed, one of Which, on the Sava riverbank, was fortified. As a result of 23 years of construction works under Serbian rule, Belgrade’s massive ramparts, towers and gates encompassed and protected an area ten times larger than before.1

In the next period, under Hungarian rule from 1427 to 1521, not much was done in strengthening the fortress. In spite of the constant, imminent threat of Ottoman attacks and two sieges in 1440 and 1456, only a few new fortifications were built: the polygonal cannon tower on the north-eastern side of the Upper Town, today known as the Jakšić Tower, and the bigger one erected on the Danube bank – today’s Nebojša Tower. Also, the eastern gates of the Upper and the Lower Town were reinforced by building the barbicans in front of them.2

Following the Ottoman conquest in 1521, the Belgrade fortress lost its strategic importance. Due to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire further to the north, Belgrade ceased to be a border stronghold between Christianity and Islam and served primarily as a large military logistics centre, winter quarters during European campaigns, a seat of the provincial governor (sancak bey) and big treasury.3 Therefore, in the first century-and-a-half of Ottoman rule, much of the construction works were focused on building a cannon foundry, powder mill, storehouses for food, grains and military equipment, mint and other such edifices.4 Building new modern fortifications was not of prime concern for the Ottomans; existing ones were used and repaired according to needs.5 The only large restoration, prior to the last decades of the 17th century, was conducted after a powder explosion in 1564. The explosion occurred in the Castle, called by the Turks Narin kalesi, and was caused by lightning to one of the Castle’s towers where the powder was placed. Besides the tower, a part of the underground treasury was demolished too, as well as many other buildings in the Upper and the Lower Town. Even the Danube port suffered damage. The construction works started in 1565 and lasted almost a decade. Yet, in spite of that experience, gunpowder continued to be stored in the Narin’s towers. Following the Ottoman conquest in 1521, the Belgrade fortress lost its strategic importance. Due to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire further to the north, Belgrade ceased to be a border stronghold between Christianity and Islam and served primarily as a large military logistics centre, winter quarters during European campaigns, a seat of the provincial governor (sancak bey) and big treasury. Therefore, in the first century-and-a-half of Ottoman rule, much of the construction works were focused on building a cannon foundry, powder mill, storehouses for food, grains and military equipment, mint and other such edifices. Building new modern fortifications was not of prime concern for the Ottomans; existing ones were used and repaired according to needs. The only large restoration, prior to the last decades of the 17th century, was conducted after a powder explosion in 1564. The explosion occurred in the Castle, called by the Turks Narin kalesi, and was caused by lightning to one of the Castle’s towers where the powder was placed. Besides the tower, a part of the underground treasury was demolished too, as well as many other buildings in the Upper and the Lower Town. Even the Danube port suffered damage. The construction works started in 1565 and lasted almost a decade.6 Yet, in spite of that experience, gunpowder continued to be stored in the Narin’s towers.

The unsuccessful siege of Vienna in 1683 followed by the loss of territories in southern Hungary, and rapid advance of Habsburg troops towards Belgrade, forced the Ottomans to strengthen the fortress in summer 1688. However, the lack of time and money enabled only minor works to be completed; several earth-filled artillery bastions were made, as well as trenches all along the Sava and Danube banks.7 But this was far from enough. The obsolete and weak system of Belgrade medieval fortifications could not resist artillery attacks for a long time. After less than a month of bombardment, Habsburg forces entered the fortress through destroyed Upper Town ramparts.8

By conquering Belgrade on 6 September 1688, the Austrians gained an important strategic base for further offensive operations deep in the territory of the Ottoman Empire. Although a great part of their forces had been transferred to the western front on the Rhine, opened in early 1689 by Louis XIV of France, the rest of their units, with the help of Balkan Christian rebels, seized, by the end of October 1689, the towns of Kruševac, Koznik and Maglič in the southwest, Niš, Pirot and Bela Palanka in the southeast, and Priština, Skopje and Prizren in the south. The Danube towns of Orșova, Kladovo and Vidin were captured too. The Habsburg commander-in-chief in Serbia, Friedrich von Veterani, planned to seize Constantinople the following year and to relegate the Turks to Asia, even though they regained Macedonia and Kosovo in December-January 1689—1690.9

Being deep in the territory under the control of the Habsburg Monarchy, Belgrade was populated by German and Hungarian bureaucrats, merchants, artisans and their families soon after the conquest.10 The Belgrade fortress was treated as if it were a definite Habsburg possession and therefore only the most urgent repairs were done.11 No one among the Habsburg commanders expected the Ottomans to regain Serbia in the late summer of 1690, in the relatively short period of time.12 Even after the fall of Smederevo (only 50 km far from Belgrade) on 27 September, general Aspremont, the commander of Belgrade at the time, wrote to his superiors that “he was not convinced the enemy would come here as everyone said”.13 The only thing he had done before the Ottoman advance guard appeared was to erect several redoubts on the Danube side. He ordered the varos of Belgrade to be burned and the citizens to leave the town and move to safer areas.14

The Ottoman siege of Belgrade started on 2 October and lasted only a week. It has been more or less thoroughly discussed in German and Serbian primary and secondary sources15, as well as in contemporary Ottoman Turkish chronicles.16 All sources agreed that defenders successfully resisted until 7 October when they were forced to leave their outposts and to withdraw behind the city walls. It is uncertain for how long the siege would last and how it would end had it not been for the great explosion in the powder magazine in the city Castle. The Inner fort wall and towers facing the Sava river tumbled down with all batteries and personnel; more than a thousand Habsburg soldiers died in the blast. The whole city was covered by a thick cloud of smoke and dust; stones, bricks, and earth were flying through the air and nowhere was safe. Later, general Aspremont reported that he jumped through the window of his house since the door was blocked by debris. He could not bring anything with him except the clothes he had on his back; he left all his belongings, household items, silverware, jewellery, and even his wedding ring. Together with Herzog Carl Eugen von Croy and one officer, he escaped to Osijek.17 Until the evening of 8 October, there were no Christians in the fortress. According to the Ottoman chroniclers, between five and eight thousand people were killed and the same number perished in the explosion or drowned in the river trying to escape.18

The explosion of the powder magazine in the Inner fort – Narin left a deep impression on contemporaries. One of them, Abdullah bin Ibrahim nicknamed Üsküdarî19 depicted this event in a particularly lively and dramatic manner with many details which could not be found in other sources. Üsküdarî is the author of the chronicle titled Events of the Passing Days, Events of the Sultan Süleyman the Second’s Campaign, covering the period from 1688 to 1693.20 Born in the early 1640s, he entered palace service in 1652, as a protégé of eunuch Bilal Agha, the teacher of Sultan Mehmed IV, and in the next four and a half years he passed general training as an apprentice (crak). After that he was attached to the Sipahi regiment for another four-year period of military training. In 1659/1660 he became a clerk’s apprentice in the Mevkufat bureau.21 Uskiidari, who according to his own statement, took part in every Ottoman campaign since 165722, was in his 50s when he began to write Events of the Passing Days. His ambitious work, done in the form of diary, represents the most detailed historical narrative yet discovered that covers any period of Ottoman history.23

Day by day, Abdullah Efendi recorded the events which he personally witnessed or heard about from reliable sources. He reported about the siege of Belgrade quite elaborately, but from a safe distance, from a military camp. When the town was captured, he went around a major part of the varos and looked into every corner of the fortress. Everything he saw, he described in his diary.

The Ottoman camp was in the place where the army always stayed when they went to European campaigns — the Vraéar field. On the elevation the Ottomans called Sultan’s hillock (Hünkar tepesi), surrounded by a trench, there was the tent of the commander-in-chief grand vizier Fazil Mehmed Pasha Köprülü.24 In its immediate environs, near the present-day St Sava Temple, there was the summer residence of the well-known vizier Abaza Mehmed Pasha (died in 1634) which, owing to its elevated position and good view of the Belgrade fortress, often served as a residence and the chief headquarters of military commanders.25 Abaza’s residence (Abaza köşk) was one of the palaces erected outside the Belgrade varoš and one of favourite outing spots for Belgraders.26

The first struggles began on 2 October, after Ottoman units formed a siege line in three wings. On the Danube side, near the Fish Market, elite Sultan’s cavalry soldiers —Kapıkulu sipahis and provincial troops from Egypt took their positions. On the Sava side, there were silahdars — another part of the Sultan’s cavalry, as well as provincial troops of Rumeli and Albanian infantry. The janissaries were in the centre. They erected their breastworks (meterises) in the middle of the Belgrade varoš, opposite a bezistan with a large han, where Habsburg soldiers were stationed. In the first attack, carried out from all three sides at the same time, only the janissaries made success, while the others were easily pushed away. “The janissaries seized a large han with bezistan, and the infidels fled away and found shelter near the Arsenal in the quarter of cauldron makers (Kazancılar mahalle) overlooking the fortress”.27

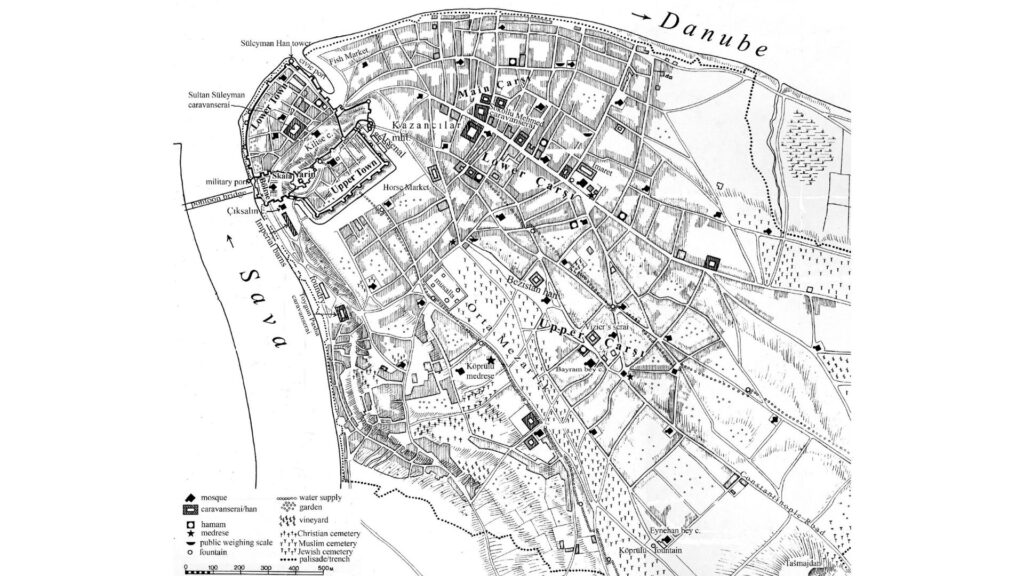

The bezistan with the large han, mentioned by Üsküdarî, was the third trade facility of this type in 17th-century Belgrade, hitherto unknown.28 It was probably located south-east from the Arsenal (Topyeri; Tophane) in the Upper çarşı (see the map enclosed). It is doubtless identical to Bezistan-han (Bezzâzistân hânı), mentioned in 1660.29

Üsküdarî did not leave a lot of data about the Belgrade varoš. He focused almost exclusively on the fortress, particularly the Lower Town. His description of the Lower Fortress (Aşağı Kale), though much shorter than the far better known description made by Ottoman travelogue writer Evliyâ Çelebi, brings new details which supplement the topographic picture of Belgrade in the 17th century.

“On one its side, this fortress leans on the Upper Fortress. In the west, its rampart stretches along the Sava bank up to the Danube bank, to the place called the Fish Market, which lies opposite Srem, where the two rivers meet. There are also the Belgrade pier (iskele) and customs (gümrük). It was on this place that late Suleyman Han built a large tower.30 From this tower, the fortress rampart goes towards the varoš mahalles, passes by the storehouses31 and reaches the quadrangular Upper Fortress. The rampart going down from the Upper Fortress is divided into several places by towers and walls. This part is called Skala (iskala) and within it there is a gate for the Lower Fortress32 and a gate for the outside which opens towards the [old] storehouses.33 The Lower Fortress has five more gates, three of which open towards the Sava river and two towards mahalles [of the Danube varoš]. There is water in front of one of these gates, which is why a wooden bridge is used to cross it. There is a tower in the Upper Fortress featuring a large clock which chimes each hour, both day and night. During the midday and afternoon prayer, a banner is hoisted on this tower. In the Lower Fortress, near the mint, there is a large mosque originating from a church, and another mosque called Imperial.”34

What is interesting in this description is the Skala toponym, which is not mentioned by other travel writers. For Üsküdarî, Skala is a part of the Lower Town fortress surrounded by special ramparts, i.e. the fortified Western Suburb of Belgrade, created back in the 14th century, which the Turks usually called a “separate fortress” (bölme hisar). The hitherto only known mention of Skala was in Ottoman censuses of Belgrade from the second half of the 16″ century, where the mahalle in Bölme hisar is mentioned under that name. The exact position of this neighbourhood was not ascertained as there was a dilemma over whether the origin of the name had to be sought in the Italian word scala (stairs) or Turkish iskele — pier.35 However, as iskala (ﻪﻠﻗﺴ) and iskele (ﻪﻠﻜﺴا) are written differently and are, as such, separately mentioned in Üsküdari’s description of the Lower Town, it is clear that those were stairs. A woodcut printed by Wolfgang Resch in 152236 and the illustration of Fugger’s chronicle from 155937, show stairs going down from the Castle to the Western Suburb, along the rampart dividing the Suburb from the rest of the Lower Town.38 They can also be recognised in Evliyâ Çelebi’s description of one of gates on the western side of the Upper Town, which reads: “There is another gate leading to the Lower Fort – it is a small gate with stairs turned to the north”.39

Based on the above said, it is possible to conclude that in the 16th century, the Skala mahalle stretched along the northern rampart of the Western Suburb – Bölme hisar, while the remaining area, particularly the flatter part along the Sava river, was occupied by another, much more populated mahalle of Hacı Hasan Agha’s mescid.40 In the 17th century, the name Skala seems to have broadened to include if not all, then certainly the higher part of the “separated”, i.e. Bölme fort.

Üsküdarî also states that there was a new pontoon bridge across the Sava river in front of Bölme hisar. It was set up by Austrians, who previously removed the old one.41 As reported by witnesses on the Ottoman side, already from the first day of the siege, Hungarian horsemen were crossing it by night. To prevent further dissipation of the garrison, on the fourth day of the siege Austrians removed a part of the pontoon so that no one could cross to the Zemun side. After they captured Belgrade, Ottomans removed this bridge entirely as it was too narrow and began to build a new one from wider pontoons.42

In the first several days of the siege, there were no changes in positions of defenders and attackers, and Üsküdarî placed a stronger focus on the Ottoman conquest of the nearby Avala fortress and Tatar attacks at Pančevo and Bečkerek.43 Only the conquest of the large bastion, built by Austrians near the Süleyman Han tower on the Danube bank, attracted his attention. Intensive struggles for this protruding artillery position lasted for two days, with varying fortune. On 6 October, after hours-long bombing, the Kapıkulu silahdars made an onslaught at the bastion and, after suffering significant losses, forced the defenders to withdraw. Then, however, a scuffle for the spoils took place. Other Ottoman soldiers in nearby meterises left their positions and began to take out the remaining weapons from the bastion and other military equipment, cut off heads and take captives. Then they headed off to the grand vizier’s tent on Vračar to show the spoils, hoping for a good award. Few of them remained in the bastion. While the spoils were being shown and awards given to the meritorious ones near Abaza’s villa, Austrians attacked the bastion and recaptured it. Until the end of the day, both parties took the position several times. By the evening, it remained in Christian hands, but several hours later, near midnight, Ottomans finally took it. On 7 October, all Austrian soldiers were pushed away from the Danube bank to the Lower Town.44

The following day, Ottomans reinforced their breastworks with another 500 fresh soldiers and began to dig underground tunnels – lağims, and set up mines. During that time, in the Belgrade fortress, the new commander Carl Eugen von Croy made plans to carry out a simultaneous onslaught at all enemy’s positions, with the reinforcement of 6000 soldiers who had arrived in Belgrade over the previous two nights.45 However, all plans were foiled when the powder storeroom in the Narin fort exploded at around four o’clock in the afternoon.

“A grenade, thrown out during the afternoon prayer from the wing of the noble vizier Halil Pasha fell into the Inner Fort, on top of one of the two towers turned towards the illustrious Çıksalın mosque, which has for ages leaned on the Imperial barns on the Sava river, and caught fire. As the said towers were replete with the stored black gunpowder, fire blazed up, the wall between the two towers went into air and huge black smoke appeared. Heroes in meterises thought it was an explosive mine, while the rest of the army was bewildered: “Aaah! What a big smoke! What is this black smoke?!” Wind then slit the smoke into two, and one could see that gunpowder razed to the ground the towers and fortress wall. While it was being determined how many Muslim gazis lost their lives in the meteris near the fortress wall – God help us – at that moment, from the wing of old and aged Halil Pasha, the Rumeli Beylerbeyi Mustafa Pasha in person, also known as the former alaybey of the right wing (sağ kol), attacked the first the Inner Fort. He called standard-bearers, Rumeli zaims and timar holders and the valiant Albanian infantry to an onslaught with the words: “My falcons, this is the opportunity and place to gain spoils! Let us push on and attack the fortress!”46 As soon as he said that, all flag-bearers and all brave men in meteris burst into the fortress. The damned ones and losers thought about opposing and fighting them; however, with the help of eternal God, the wind of victory began to blow from the Islamic side. They [Christians] had no strength to retaliate and jumped out of the moat, fleeing towards the Danube bank. Our heroes saw this, pushed after the cursed ones and made sure that their swords be fed with them. During this time, the heroes in meteris on the Danube bank drew their swords and met the enemies so that they were found in the middle and were all cut down from both sides; the soil in the fortress could not be seen from their corpses. Those who fled threw themselves into the Danube and drowned. Some entered ships, but the majority of them became food for the gazi swords.”47

The grenade which caused the powder explosion hit one of the two towers on the south-western side of the Castle i.e. the Narin fort. Based on contemporary accounts, confirmed by archaeological excavations, the Narin ramparts on the southern and western sides and all buildings were destroyed by the strength of the blow. Later, as we will see, the part of the southern rampart of the Western Suburb with the tower would be destroyed too. Owing to Üsküdarî, it is now known that the grenade was fired from the direction of the Imperial storehouses on the Sava river, wherefrom the Ottoman breakthrough to the town was made. However, his testimony reveals another, hitherto unknown detail from the topography of Belgrade – the position of the Çıksalın mosque.48

This, probably a very old mosque (kadîmden mîrî anbarlara muttasıl Çıksalın cami- i şerif), leaned on the wall–fence of the Imperial barns, a strategically important complex erected after the conquest of Belgrade in 1521.49 The barns, made of brick or stone at the time of Evliyâ Çelebi, were situated on the Sava bank, on an elevated piece of land, doubtless to be protected from floods. Their total length was 300 steps. With the high surrounding wall, they stretched 450 steps in length and over 50 steps in depth.50 They consisted of two identical buildings which stored honey, butter, rice, wheat, barley, hardtack, flour, naphtha, tar, cannonballs and ammunition stocks.51 In the city plans from the late 17th century, the storehouses were drawn in the foothill of the Sava slope, along the road leading towards the fortress Sava gate.52 We believe they were located in the area where present-day Pariska, Karađorđeva and Bulevar vojvode Bojovića Streets meet, i.e. above these roads, because Evliyâ emphasises they were located on an upper portion of land. Their position on an elevation confirms in a way the name of the mosque erected in extension.

The compound Çıksalın (Çık-salın) literally means “Come out and show yourself”. Its meaning is: “Get out, walk around, show your beauty, wealth and power to the entire world”. In the function of a toponym, it was given to places that stood out with their beauty and elevated position, with a view and freely streaming air. Such place is, for example, a hillock above the Golden Horn in Istanbul, opposite Eyüp. According to tradition, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror gave it the name Çıksalın, enchanted by the view.53 The position of the Belgrade Çıksalın mosque, above the Sava river, with a view to both rivers and the vast plane, fully corresponds to the above description. It still remains unknown from which side of the Imperial storehouses the mosque was built. This question is unequivocally solved by city plans from 1689–1690, where the mosque was drawn near the northern wall of the buildings, i.e. opposite the Bölme hisar rampart.54 This position is quite expected given that Toygun Pasha’s caravanserai was located south to the Imperial storehouses, leaning with its back against a cliff, near today’s Great Staircase.55

Further describing the consequences of the explosion in the Narin fort, Üsküdarî notes that all houses in the Upper Town suffered damage. Parts of towers and ramparts collapsed on horse stables in the Lower Town and entirely destroyed them. Fire engulfed several other buildings at the foot of Narin and spread rapidly to the entire Lower Town. It soon reached the cannon bastions next to which grenades filled with powder and other ammunition were piled. At one moment, several tens of grenades exploded simultaneously and many thought that the fight with the Habsburgs continued. This large explosion was followed by a series of smaller explosions in various parts of the Lower Town. Fire flared up with such intensity that no attempts were even made to extinguish it until the following morning. In the large caravanserai of Sultan Süleyman, opposite the Church-Mosque (Kilise camii)56 around 30.000 oat bushels (around 770 t) caught fire, burning the following eight days. In addition to this great quantity of horse fodder, around 1500 flour barrels, intended for Habsburg garrisons in Smederevo, Vidin, Hram, Golubac, Orşova, Modava and other fortifications, with total around 500 t of flour were piled near the Sava rampart. They were also caught up in fire, vanishing altogether.57

While individual explosions of artillery munition continued to sporadically resonate and fire engulfed the last remaining houses in the Lower Town, a scuffle for the spoils took place in the fortress. In larger houses in the Upper Town, which were still not caught by the fire, Ottoman soldiers plundered all sorts of items – clothes decorated with gold and silver threads, silver dishes, jewellery and money. However, those who stormed the Castle treasury found only scattered corpses and a bunch of burnt luxurious objects and money.58

During that time, the surviving Christians struggled over the ships in the Danube port. Those who managed to paddle towards Great War Island (Veliko Ratno ostrvo) saved themselves, but they were few. In the indescribable hustle and tumult, boats clashed and sank in the middle of the river, with the majority of runaways drowning in attempts to swim to Great War Island. Turks prevented twelve boats to set sail, captured people and looted the items on boats. More than 40 vessels with around 2500 Christians remained without rudders and the stream took them down the Danube. Some tried to reach Pančevo, but failed to do so in a night without moonlight. It is assumed that the majority of them drowned, while the rest were caught by Ottoman raiders. Those who tried to save themselves going upstream the Danube had no better luck. They were captured near Slankamen by Tatars, who brought them to Belgrade already the following day to sell them in the military market.59 A number of German girls and women and some Cossacks were also captured in the Belgrade fortress. The Cossacks ended up in the military market, while women, particularly girls, ended up in military tents where they were sold in secret, at high prices.60

That night, while plunders and disorders still lasted, Belgrade came under a heavy rain. Many in the Sultan’s army interpreted it as a God’s blessing as there had been no rain since the town was sieged. They hoped it would extinguish the fire that blazed in the town, but this did not happen.61 At dawn, hundreds of janissary water bearers began to bring water from the Sava on horses and quench the fire. However, it was hard to rein in fire. At some moment, it reached one of the Bölme hisar towers where, as it turned out, gunpowder and artillery munition were also stored. A heavy explosion broke out. The tower was razed to the ground and ignited grenades dispersed, bursting into thousands of lethal pieces. Many Ottoman soldiers lost their lives, most of them water bearers whose shrieks reverberated across the town.62

After a new devastating explosion in Bölme hisar, which took tens of lives, it was ordered that the corpses be taken away immediately before their stench began to spread in the fortress. The bodies of defenders and attackers lay scattered in the Upper and Lower Town, in ditches, streets, burnt remains of houses. To remove the corpses, each tent of craftsmen serving in the Ottoman army – the so-called orducus, had to give one man each for this job. An hour later, however, it was ascertained that the number of the dead was so large that it would take five to ten days to throw them all to the Sava and Danube. For that reason a new order was issued that each day, between 300 and 400 orducus should take away the corpses.63

The removal of the debris of the collapsed towers and ramparts began at the same time. That job was performed by villagers from the Belgrade environs. However, to build new fortifications and repair the damaged ones, it was necessary to engage trained people, but they could not be found at the moment. Therefore, a ferman was issued to bring stonemasons, lime-makers and carpenters from Bosnia, the environs of Niš, Sofia and Vidin. The order, issued to local kadis, defined the number of workers to be engaged and the amount of their daily allowances. A few days later, within preparatory works to restore the fortress, a ferman was also issued to gun carriage drivers (top arabacıs) to go to Avala with three hundred vehicles, cut down wood and unload it at places where lime would be made.64

On the second day of conquest, Abdullah Efendi nicknamed Üsküdarî went to look around the Belgrade varoš and fortress and see personally what he had written about based on statements of other people – eyewitnesses, experts, officials, or based on documents he had access to. The Belgrade varoš was burnt down on the eve of the Ottomans’ arrival, but larger solid buildings survived. The medrese of grand vizier Ahmed Pasha Köprülü, which consisted of twenty vaulted and lead-covered rooms built around a large internal yard, lay intact and was prepared for the accommodation of Tatar Han Selim Giray who had just arrived in Belgrade.65 The varoš streets were full of people, soldiers, craftsmen, merchants and all others who followed the Ottoman army in the campaign. Among them, there were many former Muslim inhabitants of Belgrade, who had fled the town on the eve of the Austrian siege of 1688. The day after the town was conquered the grand vizier issued a ferman, confirming them the validity of their old title deeds.66 There was also a lot of Christian reaya in the varoš. Besides those engaged in cleaning up the rubble, there were numerous representatives of villagers from Srem, Belgrade environs, Pančevo and other places. They came to pay respect to the grand vizier asking for forgiveness in relation to their participation in the war on the side of the Habsburg Monarchy. Mustafa Pasha Köprülu issued a decree of pardon (amanname) for all reaya who opposed the Ottoman rule. In a similar vein, he ordered the reaya captivated by the Tatars and exhibited for sale as slaves, to be liberated and given the permission to freely return to their homes.67

Walking around, Üsküdarî also reached the tent of military doctors – surgeons. He heard from them that they had worked during the previous two days and two nights almost without repose. Several thousand people, with injuries rarely suffered in combat, went through their hands. Most of them had severe burns, resulting from the scramble for spoils. A large number of plunderers (yağmacılar) were maimed as they had entered every corner of the fortress, burst into collapsing houses, climbed burning towers, tried to seize valuables from the Belgrade treasury that was on fire. The main surgeon, a certain Hamzaoğlu, had the largest number of the wounded in front of his tent as the wounds that he tended to purportedly healed faster than those treated by other doctors.68

Üsküdarî then entered the Upper Town. While looking around the destroyed Narin fort, one of acquaintances and friends that he walked with told him that, several hours before, workers cleaning up the rubble found three barrels full of Austrian groschen (7500 in each barrel). The defterdar was informed immediately, but before he arrived, workers and others who found themselves there had grabbed most of the money. The defterdar managed to seize only one barrel in favour of the state. This money seems to have been part of a great dispatchment of 50 barrels that arrived from Vienna fifteen days before the start of siege of Belgrade, and was intended for the payment of Habsburg garrisons in Belgrade, Smederevo, Niš, Vidin and other places. As an experienced financial expert, Üsküdarî immediately calculated that 50 barrels, i.e. 375.000 groschen corresponded to the annual salary of 30.000 soldiers. He concluded that such numerous forces and quantity of stored weapons, found first in Niš and now in Belgrade, showed that the Habsburg Monarchy was preparing to conquer Constantinople.69

Going down the streets to the Danube port, they saw, next to the Süleyman Han’s tower, a large quantity of powder in barrels with the label “ammunition for Constantinople”. Cannonballs, grenades of all size, and more than 50 balyemez cannons for cannonballs weighing 22–25 kg were piled in front of one of the river gates. There were also many pickaxes, shovels, grapnels and other tools and wooden boxes with bullets, also with the designation that they were intended for the conquest of Constantinople.70 Documents in different formats, most probably parts of the Habsburg archive in Belgrade, lay scattered around. Üsküdarî and his friends were particularly interested in two large, densely written sheets stamped with several black and one red stamp. They called one of scribe’s assistants who knew German to translate them. It turned out those were letters of Emperor Leopold I. One was addressed to Elector of Bavaria Maximilian Emanuel, after the conquest of Belgrade in 1688. The Emperor congratulated him on seizing the Belgrade fortress and ordered that the army should continue towards Niš and capture it as this would facilitate the breakthrough towards the Ottoman capital. In another letter, the Belgrade commander was informed that chaikas (type of boat) were sent from the Danube island of Komoran, loaded with ten thousand barrels of wine and three thousand barrels of brandy for troops to head towards Edirne and Constantinople.71

These vivid and detailed Üsküdarî’s observations show the importance of Belgrade as a logistics centre, but, even more importantly, the seriousness of Habsburg court’s plans about the conquest of the Ottoman capital. With the loss of Belgrade, the hopes of Holy League members that Turks would be banished from Europe were dashed. At the same time, the Ottoman conquest of Belgrade had an exquisite symbolic importance for the Empire. It showed that the Ottoman state was able to overcome a deep crisis and restore a large part of lost territories in a short time. For inhabitants of Istanbul this was the sign that they could return to a normal life. According to the testimony of an anonymous Ottoman chronicler, they lived until then in the fear of the arrival of Christian armies.72

The army of grand vizier Mustafa Pasha Köprülü stayed in Belgrade for around another three weeks. All that time, Üsküdarî no longer entered the fortress where extensive construction works began, but continued to report about them. It was envisaged that Narin be restored according to old plans or, in words of Abdullah Efendi: “As the Belgrade Inner fort burnt down altogether, with walls entirely ravaged, the digging of the rampart foundations and construction based on the old picture began” [underlined by T. K.]. In addition, vizier Hüseyn Pasha was invited from Niš. Several years earlier, while serving as the Edirne Bostancıbaşı, he stayed in Belgrade to collect provisions when fire broke out in Narin. The reconstruction that followed was carried out under his supervision. As Hüseyn Pasha was well-familiar with the appearance of towers, he now supervised the digging of foundations. As soon as the foundations of the collapsed part of the fortification were revealed several days later, he returned to Niš.73

The Ottoman army also began with preparations for return. Members of the Belgrade and Smederevo garrisons remained in Belgrade, as the latter could not spend winter in a burnt fortress.74 Over 10.000 soldiers remained in Belgrade, while others began to leave the town on 31 October. The army was divided into two parts. The artillery, supply train, craftsmen (orducus) and merchants returned to the capital by the Constantinople road, while the janissaries and cavalry took the Danube road, reached Vidin and progressed towards Constantinople.75

Construction works continued. However, contrary to the original idea, restoration was eventually carried out according to the design of Venetian engineer Andrea Cornaro, who had led Austrian works on the Belgrade fortress and, after the conquest, entered Ottoman service.76 His plan did not imply the restoration of destroyed Narin. The rubble of the erstwhile Despot’s Castle was entirely removed. In its place, the construction of Pasha’s residence and military barracks was planned.77

The Ottoman conquest of Belgrade in 1690 led to a turnabout in the relations between the warring parties in the Balkans. The war was shifted to the territory of southern Hungary. Belgrade became the main Ottoman border fortification. In the following years it assumed the characteristics of a modern artillery fortification, while its medieval features were gradually disappearing.

Belgrade in 1690, based on the map in X. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 36-37, authored by Željko Škalamera

Tatyana KATİÇ

YIKIMA UĞRAMIŞ ŞEHRİN İÇİNDE DOLAŞMAK: 1690 YILINDA BELGRAD KALESİNİN YIKIMINA TANIKLIK EDEN BİR KİŞİNİN ANLATIMI

Özet

Belgrad’ın 1688 yılında fethedilmesi, Habsburg Monarşisi’nin, Osmanlı-Kutsal İttifak Savaşları’nda Osmanlı İmparatorluğu karşısında elde ettiği en önemli zaferlerinden biriydi. Fetihten sonra devam eden Habsburg askeri başarıları göz önünde bulundurulduğunda şehir, uzun bir süre boyunca Hristiyan hâkimiyeti altında kalacağa benziyordu. Ancak Osmanlılar, 1690 yılının sonbaharına kadar Sava ile Tuna nehirlerinin güneyindeki tüm toprakları tekrar ele geçirmeyi başarmıştır. Başardıkları ‘rekonkvista’ nın en büyük galibiyeti 8 Ekim 1690 yılında gerçekleştirilen Belgrad’ın yeniden fethiydi. Şehrin kuşatılması sadece bir hafta sürmüş olup Osmanlıların şansına Yukarı Hisarda yer alan barut deposunun kazayla patlaması ile son bulmuştur. Türk kumbaraları (bomba), içinde bol miktarda barut ve mühimmatın saklandığı Narin kulelerinden birinin üst kısmına isabet etmiş ve yangına yol açarak büyük bir infilakı tetiklemiştir. Patlamanın güçlü tesiri ile Despot Stefan Lazareviç’in eski kalesinin bazı kısımları yerle bir olmuş, açılan gediklerden de şehre girilerek fetih gerçekleşmiştir.

Bu patlama, o dönemde yaşayanların üzerinde derin bir iz bırakmış olup pek çok tarihsel kaynakta tasvir edilmiştir. Bu kaynaklardan biri, özellikle ayrıntıların zenginliği ve otantik, etkili tanımları ile diğerlerinden ayrılmaktadır. Günlük biçiminde yazılan bu tarihsel çalışmanın başlığı Vâkı’ât-ı Rûzmerre, Vâkı’ât-ı Sefer-i Sultan Süleyman-ı Sânî, ya da kısa ismi ile Süleymannname’dir. Eserin yazarı Belgrad kuşatmasına ve Narin patlamasına tanıklık eden Abdullah bin İbrahim el-Üsküdari, fetihten sonra tüm kaleyi gezerek yıkımın derecesini görme imkânına sahip olmuştur.

Üsküdari, söz konusu olayların tasvirinde kuşatma ve fetih ile ilgili, bugüne kadar bilinmeyen pek çok detayın yanı sıra 17. yüzyıldaki Belgrad topografyasını da gözler önüne sermiştir. Osmanlı kuşatma birliklerinin ayrıntılı planlarının yanı sıra yukarıda bahsi geçen kumbaranın ateşlendiği pozisyonu da aktarmıştır. Maddi kayıp ve insan kaybını, özellikle de yangından etkilenen Aşağı Hisardaki kayıpları etraflıca tasvir etmiştir. Aşağı Hisardaki yangın bir haftadan uzun sürmüş ve diğer hasarların yanı sıra başka bir küçük barut deposunun patlamasına da sebep olmuştur. Bu deponun içinde bulunduğu Bölme Hisar kulelerinden biri tamamen yok olmuş ve sonrasında da yenilenmemiştir. Üsküdari, Bölme Hisar – tahkimatlı Batı Alt Kale’den bahsederken aynı yer için Skala adını kullanarak 16. yüzyıldaki kayıtlarda yer alan Belgrad mahallesi Skala’nın (Merdivenler) yerine ilişkin birtakım tereddütleri giderecek bilgi vermiştir. Üsküdari, aynı zamanda daha önce yeri hakkında bilgi bulunmayan Belgrad camilerinden biri olan Çıksalın Camii’nin de yerini kesin bir şekilde belirtmiştir. Bu cami, bugün Pariska, Karadjordjeva ve Voyvoda Boyoviç caddelerinin kesişme noktalarında bulunduğu tespit edilen Sava nehri üzerindeki eski devlet ambarlarının yakınında yer alıyordu. Üsküdari, aynı zamanda şehirdeki bu tarzda üçüncü ticari yapı olan ve tarih yazımında bugüne kadar yer almamış Büyük Hanlı Bezistan’dan da bahseder. Bu bina, Evliya Çelebi’nin bahsettiği Bezazistan-Han ile aynı yapı olup Belgrad’ın Yukarı Çarşı bölgesinde bulunuyordu. Üsküdari, bunun yanı sıra, Köprülü Ahmed Paşa medresesi ve Avusturyalılar tarafından Bölme Hisar önünde inşa edilmiş Sava üzerindeki seyyar köprü gibi diğer bazı objelerin durumlarını da tasvir etmiştir.

Son olarak, Abdullah Efendi, Osmanlıların Narin’i eski planlara uygun şekilde yeniden inşa etmelerine dair teşebbüslerini de yazar. Ancak, Osmanlılar bu niyetlerinden kısa sürede vazgeçmişlerdir. Eski Despot kalesinin yıkıntıları Venedikli mühendis Andrea Cornaro tarafından tasarlanmış onarım projesine göre tamamıyla kaldırılmış olup yerine Paşa’nın konağı ve askeri kışlaların inşaatları planlanmıştır. Sonraki yıllarda Belgrad’ın ortaçağ özellikleri giderek kaybolurken topçu tahkimatını içeren yapıların önemli ölçüde çoğaldığı görülmüştür.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu, Habsburg Monarşisi, 1683–1699 Osmanlı–Kutsal İttifak Savaşları, Sırbistan, Osmanlı vakayinamesi Süleymanname, Abdullah bin İbrahim el-Üsküdari, Belgrad kuşatması

Татјана Катић

У ШЕТЊИ РАЗОРЕНИМ ГРАДОМ: СВЕДОЧЕЊЕ ОЧЕВИЦА О РУШЕЊУ БЕОГРАДСКЕ ТВРЂАВЕ 1690. ГОДИНЕ

Резиме

Освајање Београда 1688. године једна је од најзначајнијих победа коју је Хабзбуршка монархија извојевала против Османског царства у Великом Бечком рату. С обзиром на освајања која су потом уследила, чинило се да ће град дуже времена остати у хабзбуршким рукама. Међутим, Османлије су успеле да консолидују своје снаге и да до јесени 1690. поврате све изгубљене територије јужно од Саве и Дунава. Круна њихове „реконквисте“ било је освајање Београда 8. октобра 1690. године. Опсада града трајала је свега недељу дана и окончана је, на срећу Османлија, случајном експлозијом барутног магацина у Горњем граду. Турска кумбара (граната) погодила је врх једне од кула Нарина у којој је била ускладиштена велика количина барута и муниције и изазвала пожар који је довео до разорне експлозије. Од јачине детонације делови некадашњег замка деспота Стефана Лазаревића су срушени, а у тврђавским зидинама су отворене бреше кроз које је извршен упад у град.

Ова експлозија оставила је дубок утисак на савременике и описана је у више историјских извора. Један од њих посебно се издваја богатством детаља и аутентичним сликовитим описима. Реч је о историјском делу, вођеном у форми дневника, чији наслов гласи Догађаји из похода султана Сулејмана Другог или, краће, Сулејман-нама. Њен аутор, Абдулах бин Ибрахим ел-Ускудари, очевидац је који је из непосредне близине сведочио опсади Београда, експлозији Нарина и касније био у прилици да лично обиђе целу тврђаву и упозна се с размерама разарања.

Ускудари је пишући о овим догађајима изнео више, до сада непознатих података, који се тичу саме опсаде и освајања, као и топографије Београда у 17. веку. Навео је прецизан распоред османских опсадних трупа, као и положај с кога је испаљена поменута кумбара. Детаљно је описао материјална и људска страдања, нарочито она у Доњем граду који је био захваћен пожаром. Ватра у Доњем граду трајала је више од недељу дана и, између осталог, проузроковала је експлозију још једног, мањег барутног магацина. Тај магацин био је у једној од кула Болме хисара, која је том приликом сравњена са земљом и више није обновљена.

Утврђено Западно Подграђе – Болме хисар, Ускудари иначе зове и именом Скала, чиме решава неке недоумице о положају београдске махале Скала (Степенице), забележене у дефтерима 16. века. Он такође прецизно утврђује положај једне од до сада неубицираних београдских џамија – Чиксалин џамије. Ова богомоља наслањала се на ограду старих Државних складишта на Сави, за која је утврђено да су се налазила на простору где се данас укрштају улице Париска, Карађорђева и Булевар војводе Бојовића. Ускудари помиње и „велики безистан са ханом“, који је трећи трговачки објекат ове врсте у граду, до сада неразматран у историографији. Идентичан је с Безазистан-ханом Евлије челебије а налазио се негде на простору београдске Горње чаршије. Такође описује стање и неких других објеката, као што су медреса Ахмед-паше Кеприлија (Ћуприлића) и понтонски мост преко Саве којег су Аустријанци изградили испред Болме хисара.

Абдулах ефендија, на крају, пише и о покушајима Османлија да, на основу старих планова, обнове Нарин. Од ове намере су, међутим, врло брзо одустали. Рушевине некадашњег Деспотовог замка су, према новом пројекту обнове који је сачинио венецијански инжењер Андреа Корнаро, у потпуности уклоњене, а на њиховом месту је планирана изградња Пашиног конака и војничких касарни. У годинама које ће уследити Београд ће попримити карактеристике бастионе артиљеријске фортификације док ће његове средњовековне одлике све више ишчезавати.

Кључне речи: Османско царство, Хабсбуршка монархија, ВÜsküdarî II, 13a–14a.елики (Бечки) рат 1683–1699, Србија, османска хроника Сулејман-нама, Абдулах б. Ибрахим ел-Ускудари, опсада Београда.

This article is the result of the project No. 177030 of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia.

- For more detail see M. Popović, The Fortress of Belgrade, Belgrade 1991, 23, 29–37; idem, Београдска тврђава, 2, допуњено издање, Београд 2006, 85–130 ↩︎

- M. Popović, The Fortress of Belgrade, 41–49; idem, Београдска тврђава, 131–157. ↩︎

- Treasure, minted coins, collected provincial revenues, valuable arms, carpets, gold and silver objects and other precious things were stored in the fortified Castle in the Upper Town. Т. Катић, Д. Амедоски, Дарови за османску војску: прилог историји материјалне културе Београда у 16. веку, Гласник Етнографског института САНУ 64–1 (2016) 133–149. ↩︎

- Р. Тричковић, Београд под турском влашћу 1521–1804. године, Историја Београда, Београд 1995, 96. ↩︎

- M. Popović, The Fortress of Belgrade, 51; idem, Београдска тврђава, 165. ↩︎

- С. Катић, Обнова београдске тврђаве 1565. године, Мешовита грађа (Miscellanea) 29 (2008) 55–62. ↩︎

- Idem, Јеген Осман‐паша, Београд 2001, 138–139 ↩︎

- For more detail see M. Popović, The Fortress of Belgrade, 51, 53; idem, Београдска тврђава, 179–181. ↩︎

- Р. Л. Веселиновић, Војводина, Србија и Македонија под турском влашћу у другој половини XVII века, Нови Сад 1960, 127. ↩︎

- Idem, Ратови Турске и Аустрије 1683–1717. године, Историја Београда I, Београд 1974, 481. ↩︎

- The southeastern rampart, which suffered the most damage in the 1688 siege was repaired; breaches were temporarily closed, and a new gate was built. The earth-filled bastions in front of the East and West Gate of the Upper Town, previously made by the Ottomans, were reinforced but not completely finished. Those were the Staremberg’s Bastion and the Lorrain’s Ravelin. M. Popović, op. cit., 55; idem, Леополдова капија Београдске тврђаве са суседним бастионима, Наслеђе 5 (2004) 35–36. ↩︎

- For more detail on the Ottoman conquest of Serbia in 1690 see T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje Srbije 1690. godine, Beograd 2012. ↩︎

- P. R. Diersburg, Des Markgrafe Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden Feldzüge wieder die Türken, II, Carlsruhe 1842, 133; Kriegs‐Chronik Österreich‐Ungarns Militäricher führer auf den Kriegsschauplätzen der Monarchie III Theil. Der südöstliche Kriegsschauplatz in den Ländern der ungarischen Krone in Dalmatien und Bosnien, Mittheilungen des k.k. Kriegsarchives, NF III (1889) 130. ↩︎

- T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 92–93. ↩︎

- P. R. Diersburg, op. cit., 133–138; A. Arneth, Das Leben des kaiserlichen Feldmarschalls Grafen Guido Staremberg (1657–1737), Wien 1853, 127–128; A. T. Brlić, Die freiwillige Theilnahme der Serben und Kroaten an den vier letzten österreichisch‐türkishen Kriegen, Wien 1854, 80–81; К. С. Протић, Одломци из историје Београда (1688–1717), Годишњица Николе Чупића 6 (1884) 172–178; Р. Л. Веселиновић, Ратови, 481–483, 490– 495. ↩︎

- For Ottoman perspective on the siege of Belgrade see T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 91–100. ↩︎

- P. R. Diersburg, op. cit., 136–137; A. Arneth, op. cit., 127–128; К. С. Протић, op. cit., 176– 177; Р. Л. Веселиновић, Ратови, 494–495. ↩︎

- T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 99. ↩︎

- R. Murphey, Biographical notes on ‘Mevkufatȋ’ a lesser known Ottoman historian of the late seventeenth century, Essays on Ottoman Historians and Historiography, Istanbul 2009, 49–58, prefers to call him Mevkufatȋ. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî’s work, known also as Süleymanname, consists of four volumes. The first three are kept in the Archive of Topkapi Palace (Abdullah bin Ibrahim el-Üsküdarî, Vâkı’ât‐ı Rûzmerre, Vâkı’ât‐ı Sefer‐i Sultan Süleyman‐ı Sânî, I–III, Topkapı Revan Köşkü, nr. 1223–1225, İstanbul) and the fourth one in Süleymaniye Library (Vâkı’ât‐i Rûzmerre, vol. IV, Süleymaniye Ktp. Esad Efendı Koleksıyonu, nr. 2437). In this paper, I used the first and the second volume of his manuscript, Vâkı’ât‐ı Rûzmerre, Topkapı Revan Köşkü, nr.1223 and 1224, hereafter Üsküdarî I, II. Only after my work was completed did I find out that all four volumes of Üsküdarî’s chronicle were published in Üsküdarî Abdullah Efendi, Vâkı’ât‐ı Rûz‐merre I-IV, çev. M. Doğan, R. Ahıshalı, E. Afyoncu, M. Ak, Ankara 2017 ↩︎

- For more detail see R. Murphey, Biographical notes on ‘Mevkufatȋ’, 50–51. Bureau of Retained Revenues (Mevkufat kalemi) was a part of the Ottoman Finance Department which, during a campaign, made allotment of food and fodder rations to soldiers and their horses and provided salary to civil servants accompanying the army. For more detail see F. Müge Göçek, Mewkufatçi, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, vol. 6, Leiden 1991. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî I, 553. ↩︎

- R. Murphey, Biographical notes on ‘Mevkufatȋ’, 49. ↩︎

- Units of Austrian general Heisler camped on the Sultan’s hillock in 1690 and they dug out the trench. Üsküdarî I, 596, 656. ↩︎

- According to several Ottoman chroniclers, in 1688 Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria stayed there while carrying out the siege of Belgrade (С. Катић, Јеген Осман, 146; also drawn in Gump’s plan of Belgrade from 1688). In 1697, Sultan Mustafa II saw off his army to the battle near Senta from the same place (Silȃhdar Fındıklılı Mehmed Ağa, Nusretnâme, vol I, sad. İ. Parmaksızoğlu, İstanbul 1962, 303). ↩︎

- Evlija Čelebi, Putopis. Odlomci o jugoslovenskim zemljama, prevod, uvod i komentar H. Šabanović, Sarajevo 1979, 91. In 1683, somewhere on Topčider Hill, towards Dedinje, a villa was built for Sultan Mehmed IV, who stayed in Belgrade for a longer time. Abaza’s pavilion and the “newly constructed villa (belvedere) where the Great Turk lives” were drawn in the Italian plan of Belgrade of 1683, with the numbers of the legends of these two buildings obviously permuted (see Ж. Шкаламера, М. Поповић, Нови подаци са плана Београда из 1683, Годишњак града Београда 23 (1976) 38–39, 51–54). The villa of Mehmed IV, a passionate hunter, had to be located, in our opinion, closer to the potential hunting ground, i.e. farther from the town and not on the plateau of St Sava Temple where Abaza’s villa was located. The assumption of D. Đurić-Zamolo (Beograd kao orijentalna varoš pod Turcima 1521–1867, Beograd 1977, 139) that Abaza’s residence was in the Danube varoš should be entirely rejected. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî I, 657–658. ↩︎

- Known are the bezistans of grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and vali of Buda, Musa Pasha from Foča. Х. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда од 1521. до 1688. године, Годишњак града Београда 17 (1970) 20, 24. It seems that Musa Pasha’s bezistan is mentioned in the 17 th century as Arasta bezistan. Evliyâ Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi, V kıtap, Topkapı Sarâyı Kütüphanesi Bağdat 307 Numaralı Yazmanın Transkripsiyonu – Dizini, hazırl. Y. Dağlı, S. A. Kahraman, I. Sezgin, Istanbul 2001,197. ↩︎

- Evliyâ Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi, V, 197; cf. ‘Han-bezistan’ on page 88 of Šabanović’s translation of Evliyâ’s travelogue. The earlier identification with the so-called Arhinto’s house in T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 93 is incorrect. ↩︎

- Present-day Nebojša tower, built in the 15 th century. Ottoman chroniclers ascribe its construction to Süleyman the Lawgiver, though he only restored it. М. Поповић, Кула Небојша са делом Приобалног бедема и Воденом капијом II, Наслеђе 8 (2007) 9–28. ↩︎

- The storehouses mentioned here were new, erected probably in the late 16th or early 17th century in the Lower Town, while the old ones were located outside the Lower Town walls, on the Sava bank (nehr‐i Sava yalısından anbar‐i kadîm). Üsküdarî I, 657. ↩︎

- The gate on the northern rampart of Bölme hisar, the so-called Northern Gate of the Western Suburb. М. Поповић, Северна капија средњовековног подграђа на Сави, Наслеђе 17 (2016) 10. ↩︎

- The Outer gate, i.e. the gate of the Sourthern Rampart, turned towards the Sava river, was later incorporated into the complex of the new Sava gate. М. Поповић, Сава капија Београдске тврђаве, Наслеђе 10 (2009) 65–76. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 4a-b. ↩︎

- Х. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 18. ↩︎

- Cf. picture 91 in М. Поповић, Београдска тврђава, 163. ↩︎

- Johann Jakob Fugger, Ehrenspiegel des Hauses Österreich (Buch VII), Augsburg 1559 – BSB Cgm 896 ill.748–749. Available at: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/index.html?c=thema&kl=Ehrenspiegel&l=de [accessed on 25/05/2018]. ↩︎

- I am highly grateful to my colleague Marko Popović for turning my attention to these two pictorial sources. ↩︎

- “Ve bir kapu dahi Aşağı hisâra inilir nerdübânlı küçük kapu şimâle nâzırdır”. Evliyâ Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi, V, 193. ↩︎

- Hasan Agha was the commander (dizdar) of the Bölme fort. His mescid is also called the Bölme hisar mescid. X. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 17–18. ↩︎

- The old pontoon bridge was located somewhat more upstream from the new one, outside the fortification, between the Imperial barns and the Gypsy quarter. Б. Храбак, Мостови под Београдом у XVI и XVII веку, Годишњак града Београда 21 (1974) 7–8; Ж. Шкаламера, М. Поповић, Нови подаци, 54. ↩︎

- Üskügrenadedarî II, 7b, 20a, 25b. ↩︎

- About the conquest of Avala and other events see: T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 93–96. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 7b, 9b-10a. ↩︎

- For more detail see: T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 96. ↩︎

- Mustafa Pasha was among the first who lost his life from a bullet. He was buried the following day in the cemetery in the yard of Eynehan Bey’s mosque. For more detail see: T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 97. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 13a–14a. ↩︎

- The Çıksalın mosque and its neighbourhood are mentioned only in Evliyâ Çelebi’s travelogue (Seyahatnâmesi, V, 195, 196), without any indication of their location. Previous researchers have not ascertained the place where this religious building was located. D. Đurić-Zamolo, Beograd kao orijentalna varoš, 54. ↩︎

- For more detail about mahalles of Imperial barns see: X. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 11–12. ↩︎

- М. Влајинац, Из путописа Ханса Дерншвама 1553–55, Браство 21 (1927) 99. ↩︎

- Evliyâ Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi, V, 198; cf. Serbian translation Evlija Čelebi, Putopis, 89 – it contains an erroneous editor’s addition that the storehouses were located on the Danube and, also, does not mention some of the above information. ↩︎

- Ж. Шкаламера, М. Поповић, Нови подаци, 48. ↩︎

- Today, Istanbul’s quarter Çıksalın is located there. Evliyâ Çelebi (Seyahatnâmesi, IX kitap, haz. Y. Dağlı, S. A. Kahraman, R. Dankoff, Istanbul 2005, 124) notes that the Çıksalın gate, also called Papa’s gate, was located on the northern side of the Rodos fortress, by the pier. An eponymous bastion was built in front of it, in the area outside the walls, also called Çıksalın. ↩︎

- Kriegsarchiv, Wien, Klf 23–50e, published in M. Поповић, Београдска тврђава, 186. In addition, the mosque without storehouses, is also marked in the plan Kriegsarchiv, Wien, HIIIC 142. Radni katalog Planova Beograda od 1683 do sredine 19. veka (author M. Popović), which is, with all digital materials, kept in the documentation centre of the Scientific-Research Project for the Belgrade Fortress. ↩︎

- It was erected in the mid-16th century and was described by Hans Dernschwam in 1553. Х. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 32–33. ↩︎

- Formerly metropolitanate church of the Dormition of the Mother of God. For more detail see: M. Поповић, В. Бикић, Комплекс средњовековне митрополије у Београду, Београд 2004, 11–22. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 14a–15a, 16a. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 14b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 15a, 20a–b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 16a. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 18a. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 19a–b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 21a. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 21b–22b, 27b–28a. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 23a, 33a; The medrese was located somewhere in Bayram Bey’s çarşı, which stretched on both sides of the Great cemetery (the area of today’s Vasina Street) up to the Sava slope (Х. Шабановић, Урбани развитак Београда, 19, 25, 30). According to Šabanović (ibidem, 36), a line of the Belgrade water supply system went along today’s Knez Mihailova Street, along Terazije towards Vračar, where Ahmed Pasha Köprülü built a larger number of fountains and water balances, tower-like structures known as su terazisis. Therefore, we assume that his medrese was located on this road as well, probably somewhere in the area of today’s Knez Mihailova Street. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 28b. There were also over 500 Muslims in the town, who were held captive in the Belgrade fortress and liberated after the conquest. According to their statements, Austrians kept in the fortress a much larger number of Ottoman captives. Several days before the start of the siege they sent the most valuable ones by ships to Buda so as to exchange them later or sell them at high prices. Ibidem, 15b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 21a–b. For more detail see T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje, 115–116. ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 20b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 39b–40b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 41a–b. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 42a. ↩︎

- Anonim Tarihi, Topkapı Sarayı Kütüphanesi, Hazine 1468, 132a. On 10 July 1690, the day grand vizier Mustafa Pasha Köprülü went to the campaign, Istanbul was hit by a devastating earthquake. Thousands of houses were either demolished or damaged, as well as a large number of mosques, which was interpreted among people as a bad omen and sinister start of the campaign in which the last hopes were laid (Üsküdarî I, 519; Anonim, Hazine 1468, 128b). In the following three months, the life in the capital seemed to have depended on the news from the battlefield. As stated by an unknown chronicler, only when receiving the news that Belgrade was captured did the inhabitants of Istanbul liven up and, freed from fear, began to remove the rubble (Anonim, Hazine 1468, 132a). ↩︎

- Üsküdarî II, 44a–b. ↩︎

- During the withdrawal from Serbia in 1688, the inhabitants of Smederevo burnt down the fortress so that it would not serve the enemy. After the conquest of 1690, the fortress had only around ten houses, a semi-destroyed minaret without a mosque and a badly damaged hammam which was used by the Austrian garrison as ammunition storehouse. On the other hand, the rich south-western suburb lay intact and former inhabitants could move in immediately. For more detail see: T. Katić, Tursko osvajanje Srbije, 120. ↩︎

- For more detail about the return of the army by the Danube road see: T. Katić, Сувоземни пут од Београда до Видина, према дневнику похода Мустафа-паше Ћуприлића 1690. године, Историјски часопис 47 (2000) 103–115. ↩︎

- Cornaro remained to live with his family in Belgrade. In summer 1695, he received an award from Sultan Mustafa II – 200 golden coins and a ceremonial kaftan. Silâhdar, Nusretnâme, vol I, 59. ↩︎

- For more detail see М. Поповић, Београдска тврђава, 189–208. ↩︎