Anja Nikolić* DOI: 10.2298/BALC1647177N

PhD candidate Original scholarly work

University of Belgrade http://www.balcanica.rs

Similarities and Differences in Imperial Administration

Great Britain in Egypt and Austria-Hungary in Bosnia-Herzegovina

1878–1903

Abstract: This article discusses the similarities and differences of the position of Great Britain in Egypt and Austria-Hungary in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the age of New Imperialism. Comparative approach will allow us to put both situations in their historical context. Austria-Hungary’s absorption of Bosnia-Herzegovina was part of colonial involvement throughout the world. Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina were formally parts of the Ottoman Empire, although occupied and administrated by European Powers. Two administrators, Evelyn Baring as consul-general in Egypt and Benjamin von Kállay as civil administrator of Bosnia-Herzegovina, believed that it was their duty to bring “civilization”, prosperity and western culture to these lands – a classic argumentation found in the New Imperialism discourse. One of the most important tasks for both administrators was fighting the national movements, which led to the suppression of political freedoms and the introduction of a large administrative apparatus to govern the newly-occupied lands. Complete control over political life and the educational system was also one of the major features of both administrations. Both Great Britain in Egypt and Austria-Hungary in Bosnia-Herzegovina never tackled the agrarian question for their own political reasons. British rule in Egypt and Austro-Hungarian in Bosnia-Herzegovina bore striking resemblances.

Keywords:colonialism, New Imperialism, civilizing mission, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Egypt,

bureaucracy, administration, Benjamin von Kállay, Evelyn Baring

The aim of this work is to highlight similarities and differences between the “veiled protectorate” of Great Britain in Egypt and Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina. While British rule in Egypt is invariably described in historiography as colonial, that of Austria-Hungary in Bosnia-Herzegovina is still seen, at least by some western scholars, as a special case, something between colonialism and modernization. A comparison of administration in the two occupied territories will provide a clearer picture of the Dual Monarchy’s rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Comparative approach allows us to place the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in its historical context. The occupation of this land has often been studied in historiography as an isolated event without correlation with other events. A comparative method enables us to see the parallels in the events leading to the occupation of both Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the territories held by the Ottoman Empire, and notable similarities in the nature of the regimes in the occupied territories. The Dual Monarchy’s involvement in Bosnia-Herzegovina was not an exception, but rather a part of much larger colonial involvement of great powers throughout the world.

When Cecil Rhodes declared that “expansion is everything” he defined the moving principle of a new era known as “New Imperialism”. While prior to “New Imperialism” territorial and economic control had been an exclusive concern, the aim in the new period was also to impose a “higher” culture on a local one which was unable to resist the imposition. Many believed that the duty of Europeans was to bring “civilization” to distant lands and, with it, peace, prosperity and western culture. To rule the minds of the subjected people was as

important as territorial and economic rule over their land.[1]

Two new techniques for ruling over people were introduced in this period. As Hannah Arendt put it, “one was race as a principle of the body politic and the other bureaucracy as a principle of foreign domination.” [2] Race was part of contemporary explanatory discourse used to justify imperialism, while bureaucracy was used as an agency for spreading ideas associated with foreign rule. Bureaucracy was crucial to organizing expansion in both territorial and cultural sense, and was of utmost importance for further involvement and con-

quest. [3] These ideas soon met with reality in two Ottoman provinces – Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Prelude to occupation

Egypt was formally part of the Ottoman Empire until 1914. Nominally an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire from 1882 to the First World War, it was de facto a British protectorate. The British occupation had no legal basis and it appears to have been provisional in character.

Since 1805 Egypt was ruled by a local dynasty and had an almost independent status in the Ottoman Empire. Measures taken by Muhammad ‘Ali changed Egypt’s position within the Ottoman Empire. ‘Ali managed to organize local administration, create a naval force and an army, and restore finances. [4] Conflicts with the Ottoman Empire were costly for Egypt. European powers took an interest in these conflicts and the position of Egypt started to change. For Britain, it was unacceptable to have the Red Sea reduced to an Egyptian lake. The Red Sea was its vital route to India and it was necessary to keep local authorities in Egypt in check. The Balta Liman Treaty (1838) between the Sublime Porte and Britain brought an end to monopolies throughout the Ottoman Empire. Thus Egypt’s economic independence, based on monopolies, suffered a serious setback. [5] In a struggle with the Ottoman and British empires, Muhammad ‘Ali was forced to renounce his country’s economic independence but he obtained the sultan’s firman granting his male descendants hereditary rights. Along with the establishing of schools, local administration and military forces, these rights proved to be of great importance once the British entered Egypt.

After Muhammad ‘Ali’s death, his successors began to pursue a different policy. While Muhammad ‘Ali had insisted on cultural links with the Ottomans regardless of his independence, his successors cut their ties with the formal suzerain. Between 1848 and 1879 European powers took control of the country. The vast majority of Egyptian foreign trade was directed to Britain and France in the second place. [6] Egypt’s geographical location was an important factor in British involvement. Egyptian rulers needed European support to maintain order. Aware of the dangers of European involvement, they sought to exploit the differences between France and Britain. None of their plans proved successful, however, and European bankers and traders played a crucial role in establishing foreign rule. From 1854 onwards European banks were established in Egypt and foreigners were employed by the Egyptian government, particularly in the railway department. British and French control was cemented through friendship between Said, the son of Muhammad ‘Ali, and the French consul Ferdinand de Lesseps. Lesseps convinced Said that the construction of a canal at Suez connecting the Mediterranean and the Red Sea would improve Egypt’s position and make Said himself an important figure. [7] Large-scale construction works led to extensive borrowing from European banks and European control grew stronger. The initial agreement between Lesseps and Said meant that Egypt not only agreed to abandon the land along the canal and provide workforce but also renounced all income derived from transit.

Said’s death changed nothing. Ismail, Said’s successor, had no control over the country’s economy. In 1863, he faced Napoleon III’s arbitration regarding the dispute between the Egyptian government and the Suez Canal Company over the rising debt. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), which enabled Egypt’s short-lived economic growth due to the increased export of cotton, foreign bankers forced the Egyptians to spend their accumulated funds on large-scale public works and Egypt was soon left with no money to defray its rising debt. In 1875, Egypt sold its shares in the Suez Canal Company to Britain and was forced to ask for financial support from European states. European powers were now in a position to interfere in Egypt’s internal affairs. By 1878 France and Britain took over the ministry of finance. British representative Evelyn Baring would soon become the de facto ruler of Egypt.

Relations between Egypt and Britain soon mirrored those between Ismail and Baring. The latter insisted that Ismail spend all European money to bribe Ottoman officials to allow Egypt’s declaration of independence. Ismail was recognized as khedive by the Ottomans, but Egypt had little benefit from it. Foreigners filled in all important positions in the local administration and, in addition, the khedive’s power was undermined by local elites. Owing to its influence on the local administration, Britain was able to maintain its position without resorting to military force. Egyptian key officials cooperated with Britain – Nubar Pasha became the president of the council of ministers. [8] is European-controlled government was unpopular. Claiming to act in response to the discontent of the Egyptian people, Ismail proclaimed the formation of a truly Egyptian cabinet. [9]

Ismail’s feeling of triumph was short-lived. France and Britain colluded with the Sublime Porte to end the reign of khedive Ismail. In June 1879, the Ottoman sultan ordered Ismail to leave Egypt at once, and Ismail’s son Tawfiq was made the new khedive of Egypt. Baring was satisfied because, in his eyes, Ismail was the greatest obstacle to reforms in Egypt, [10] but he was also aware of difficulties in relations between locals and foreigners. He preferred Britain’s exercise of informal rule which would not lead to open confrontation between locals and Europeans.

Baring’s suspicions were justified. The growing number of Europeans in Egypt and their increasing role in the local administration and government provided further reason for tensions. [11] Tawfiq started his reign with the idea of adopting a constitution in cooperation with the younger generation of intellectuals. The idea appealed to local elites, who believed in the imminence of change, especially with Jamal al-Afghani preaching pan-Islamic ideas. With his newspaper articles, he was an early promoter of nationalism in Egypt. [12] However, the khedive changed his mind under the influence of the British consul. He abandoned his reformist position, banished al-Afghani as well as liberal journalists from Egypt, [13] and appointed Riaz Pasha as prime minister. [14] Newspapers were banned, the rest of journalists were deported. This did not help the regime. The opposition called for the necessity of a constitution, but Riaz Pasha and the khedive ignored such requests. The opposition consisted of young intellectuals, liberal pashas and army officers. One of the colonels, Ahmad Urabi, was the leader of the opposition movement which was growing stronger under the popular “Egypt for Egyptians” slogan, and culminated in the rebellion of 1879–1882. This was a matter of concern for British and French politicians and, in January 1881, they insisted that the khedive was the only guarantee of peace and prosperity in Egypt. [15] The British consul in Egypt reported that rebellions were a serious threat. France and Britain soon sent their joint fleet. That did not defuse the situation; on the contrary, it further weakened the khedive’s position. Riots in Alexandria showed the extent of the rebellion and the British bombarded the city in July 1882. Troops were soon deployed and local elites that hoped to neutralize the involvement of European powers faced the prospect of Britain’s establishing a “veiled protectorate” over Egypt.

In another frontier province of the Ottoman Empire, Bosnia-Herzegovina, the situation was as complex as that in Egypt. In April 1878, Gyula Andrassy’s memorandum explaining the reasons for the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina arrived in London. Andrassy insisted that the crises that had escalated in Bosnia-Herzegovina were a danger to Europe, and that the province would cause even more problems if granted autonomy. He gave a depiction of the internal situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina and concluded that the occupation of the province would improve the stability of the Ottoman Empire and the whole region. He pointed out that, for Austria-Hungary, the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina would be a defensive move against the danger of a possible conflagration arising from the Eastern Crisis (1875-1878). [16] Political motives are not difficult to find in this memorandum – preventing the creation of a large South-Slavic state was of utmost importance. Cultural and civilizing mission was crucial to achieving such a goal. “Altruistic” note in this memorandum was used to disguise an Austro-Hungarian proposal for carrying out a colonial exploitation in the province. [17] The Congress of Berlin allowed Austria-Hungary to occupy Bosnia-Herzegovina for a period of thirty years. The Dual Monarchy spared no effort to present the act of occupation in a positive light. It sought to show that the Balkan peoples were incapable of organizing political life on their own and could not be counted among modern civilized societies. [18] The discourse used to justify the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina was characteristic of the age of New Imperialism. European superiority was obvious when European powers were compared to the Ottoman Empire. The latter was seriously in decline, which affirmed the image of Europe as a beacon of modernity

and civilization. Bosnia-Herzegovina fitted perfectly well into that narrative. [19]

Both Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina remained formally part of the Ottoman Empire, although they were occupied and administrated by European powers – Britain and Austria-Hungary. The Dual Monarchy was given a mandate to occupy Bosnia-Herzegovina by other European powers and its rule had a legal basis. British occupation of Egypt, on the other hand, had no legal grounds.

Defining positions

Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina were occupied at almost exactly the same time in 1878. The French and British taking over of the Egyptian ministry of finance did away with any semblance of Egyptian independence. Cooperation with the Sublime Port to install a new khedive proved that Egypt was in transition from being an “almost independent” country to being under “veiled protectorate”. The Urabi revolt brought hope but it was crushed by the British force of arms. Once the British had set foot in Egypt, it was obvious that they had no intention to leave, especially because Egypt’s undefined legal status allowed for greater freedom in dealing with it. Britain had no timeframe for leaving the Ottoman territory, apart from a “promise” to the khedive that the troops would leave as soon as peace, prosperity and order had been secured.

The status of Bosnia-Herzegovina was more clearly defined since the occupation was sanctioned by Article 25 of the Berlin Treaty. However, that did not matter much for the local population – the goal of Austria-Hungary was to establish a stable regime which would lead to annexation, which was seen as the only solution given the declining power of the Ottoman Empire and the growing Serbian national movement. Just as the British had to suppress a rebellion in Egypt, the Dual Monarchy met with resistance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The resistance largely came from its Muslim Slav population; Christian Orthodox Serbs were militarily exhausted after four years of relentless fighting against the Ottomans to forge a union with Serbia and Montenegro. [20] Both Muslim Slavs and Christian Orthodox Serbs were strongly opposed to the rule of the Dual Monarchy in Bosnia-Herzegovina, while Roman Catholic Croats favoured it. [21]

Austro-Hungarian troops entered Bosnia-Herzegovina on 29 July 1878. [22] They faced a much stronger resistance than expected [23] but, considering Austro-Hungary’s mandate to occupy the province, the rebellion was doomed to failure. The issues of agrarian reform, high taxation and corruption were not, however, addressed by the time Austro-Hungarian rule ended in 1918.

British rule in Egypt was not strictly defined, as the legal position of Egypt was not clear. Bosnia-Herzegovina was under the joint rule of Austria and Hungary, and it was placed under the jurisdiction of the joint Ministry of Finance. The 1878 Treaty of Berlin did not specify the type of administration to be introduced in the occupied Ottoman province. Andrassy insisted that these lands be placed under civil control as soon as possible. The organization of a provincial government was informed by the Imperial Resolution of September 1882. [24] Evelyn Baring – later known as Lord Cromer – in Egypt and Benjamin von Kállay in Bosnia-Herzegovina became thede factorulers of the occupied territories. Both men assumed office in 1882. Baring served as British consul-general in Egypt and Kállay was appointedas civil administrator (i.e. governor) of the Condominium of Bosnia-Herzegovina by the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Finance. Both of them introduced an imperial bureaucracy in the occupied lands.

For Baring, Egypt was just a means to achieve British geopolitical objectives,a step in the process of expansion that would secure India. That determined his attitude towards the local population. He displayed an utter lack of interest in the people under his administration because, to him, Egypt was a mere, if important, theatre in which the “expansion is everything” doctrine was applied. [25] Lord Cromer was an embodiment of the transformation of temporary colonial services into permanent ones. His first reaction upon arriving in Egypt was ambiguous due to the hybrid form of government he found there. A few years later this unprecedented form of government became characteristic of most imperial administrations. [26] Cromer grew accustomed to it and soon began to point out the advantages of such methods of ruling over foreign lands. Informal influence was preferable to a strictly defined policy since it left room for flexibility and only required an “experienced minority”, as he dubbed bureaucracy, to rule over an “inexperienced majority”. [27] He expounded his complete “bureaucratic philosophy” in the essay “The Government of Subject Races”. [28]

Benjamin von Kállay presented his ideas regarding Bosnia-Herzegovina in the lecture “Hungary’s place between East and West” delivered at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1883, laying the theoretical foundation of his mission in Bosnia-Herzegovina. According to a representative of the Dual Monarchy, the cultural mission would be over once “backward” lands had been assimilated in the multi-ethnic empire. [29]

Imperial bureaucrats

Fully aware of the importance of experienced bureaucrats, both Britain and Austria-Hungary sent their skilled administrators to Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina respectively. Cromer’s and Kállay’s careers had been quite similar before they were appointed to govern the occupied provinces. They introduced an extensive administrative apparatus in the provinces under their respective administrations. The Dual Monarchy increased local administration from a total of 120 Ottoman officials in 1878 to more than 9,000 Austro-Hungarian officials in 1908.[30]

Baring at first pursued a military career, his first post being in Corfu in 1858. In 1872 he left the army and went to India, which marked the beginning of his career as a colonial administrator. [31] There he was in charge of administration and finance. He stayed in India until 1876 and his contribution to administration and especially his financial reforms launched his career. Not long after he returned from India he was dispatched to Egypt to oversee finances. He spent four years in Egypt before returning to India for a brief stay. Between 1882 and 1907 his name was a synonym for British rule in Egypt in the form of a veiled protectorate. Experienced in financial matters, he was sent to Egypt to carry out needed reform; but it did not take him long to realize that financial matters could be managed by one of his many assistants and he switched his focus to something more important – fighting the national movement.

Kállay’s career was quite similar. He too was an experienced diplomat before arriving in Bosnia-Herzegovina to rule over the occupied territory. The oft-mentioned fact that his mother was of Serbian origin had no influence whatsoever on his views, [32] but he spoke Serbian as well as English, Greek, Russian and Turkish language. He was greatly influenced by the revolutionary events of 1848, and believed that the importance of the Serbian question was obvious. He deemed it crucial for the Dual Monarchy to replace Russian influence in the Balkans with its own. So he seemed perfect for the role – he spoke the language, was respected among Serbs and undoubtedly was loyal to Hungarian interests in the Dual Monarchy. [33] In 1868, Kállay was appointed consul-general in Belgrade. While pondering how to minimize Russian influence in Belgrade, Kállay realized that the question of Bosnia-Herzegovina was crucial to the accomplishment of the Serbian national programme. There is a note in his diary that a dispute between Serbs and Croats regarding Bosnia-Herzegovina would be very beneficial to the Dual Monarchy. [34]

The unification of Germany had a tremendous impact on the policy towards Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Kállay left Belgrade in 1875 convinced that any concessions to or compromise with Serbia were impossible. The Eastern Crisis (1875–1878) would once again turn his attention to the Balkans. He soon became the finance minister of the Dual Monarchy – which meant that he was also the de facto ruler of Bosnia-Herzegovina. [35]

In brief, the careers of the two administrators were clearly similar in more than one respect. Both were experienced and highly skilled professionals, both were appointed as high officials of the finance ministry and both were familiar with the local population. Their missions also had the same objective – fighting against the national movements and securing complete control over political life in the occupied provinces, Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Facing the national movements

Once British soldiers set foot on Egyptian soil it became clear who the real master was even though Egypt remained formally under control of the Ottoman sultan. This created a legal conundrum that helped Britain to establish a “veiled protectorate”, a synonym for British rule until 1914. Indeed, constant improvisations and hybrid forms of rule were the hallmarks of foreign rule until the outbreak of the Great War. [36]

Britain claimed that its army would leave Egypt as soon as the financial situation had been settled and the authority of the khedive restored. This proved to be impossible. In 1883, Britain allowed the formation of a quasi-parliamentary institution as a sort of compromise, since the khedive, as has been seen, gave up the intention to introduce a proper constitution. The Egyptian parliament was a mere advisory body to the khedive without any real political power. On his arrival from India, Baring became aware of the complexity of the political situation. The khedive was discredited due to his overt collaboration with the European ambassadors during the Urabi revolt. Baring spent his first years as consul-general racing against the clock to stave off bankruptcy. [37] More important than keeping Egyptian finances afloat was a change in Baring’s attitude: in 1888, he insisted that British rule was necessary. He embarked on numerous reforms, which were necessary in his opinion. One reform led to another and it did not take long before this process began to serve as an excuse for the British to abandon every thought of withdrawing from Egypt. The appointment of Herbert Kitchener as chief inspector of the Egyptian police was a turning point for Baring. [38] He appointed Fahmy Pasha as prime minister and started employing the British to serve in the Egyptian administration on an even larger scale than before. [39] The number of British people in Egypt was on the rise, as Cromer insisted on settling Europeans. In 1897, there were 19,563 Britons in Egypt, a sharp rise in comparison with 6,118 in 1882. [40]

From 1891 onwards Baring was focused on fighting against the national movement. He was in complete control of Egypt’s administration and his “veiled protectorate” started to look more like a “veiled colony”. The rise of the new khedive, Abbas II, proved to be a great challenge for him. Baring – raised to peerage as Lord Cromer in 1892 – sensed trouble almost immediately. The young khedive was educated in Europe, butCromer described him as a true Egyptian in terms of his outlook. [41] While the late khedive had owed his life to the British, the young Khedive owed them nothing, which drastically changed the relations between the formal ruler and the de facto ruler. Abbas II surrounded himself with young Egyptians educated in Europe just like him, and started to question Cromer’s decisions. Egyptian students, who obtained their higher education in Europe and returned home, challenged the attitude of local population that co-operated with the British. Abbas II was one of the most important figures in the rise of Egyptian nationalism, but its true prophet was Mustafa Kamil. He stood up against the education policy pursued in Egypt that made schooling a privilege of the rich elite. Moreover, the language of instruction was English and education was, according to Kamil, designed to stifle a sense of patriotism among younger generations. He insisted that Egypt was a civilized country perfectly capable of governing itself. [42] Cromer’s last years in Egypt were marked by constant struggle with the national movement that opposed British rule. He endeavoured to limit political freedoms and became weary of quasi-parliamentary institutions even though they had almost no influence on political life in Egypt. His career in Egypt ended in 1907 when a conflict between the British and the locals led to the death of a British solider and life imprisonment for four Egyptians. The incident caused protests that worried London. Baring was soon recalled and he left Egypt for good.

In another part of the Ottoman Empire, occupied by Austro-Hungarian troops, the situation was somewhat similar. Kállay’s main objectives were to undermine Russian influence and to put an end to the idea of a large Slavic state on the southern border of the Dual Monarchy. There was no doubt that the occupation was a prelude to annexation, and Kállay openly stated so himself in a text he wrote prior to assuming office in Sarajevo. [43] On arrival he faced two problems: the national movements and the loyalty of local population. The memories of the 1878 Serbo-Muslim rebellion were fresh and Kállay was determined to prevent any future uprising. He insisted on a strong Austro-Hungarian military presence in Bosnia-Herzegovina to prevent any interference from Serbia and Montenegro, and a strictly centralist government. [44] After the rebellion Kállay feared potential cooperation between Orthodox Serbs and Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina and he brought in large military and police forces and colonized loyal population from other parts of Austria-Hungary. [45]

Although official Belgrade kept its distance from the national movement in Bosnia-Herzegovina in compliance with the 1881 Secret Convention with Vienna, Kállay saw Serbia as the greatest threat to the Dual Monarchy. The Serbian and Montenegrin borders were under strict control, and there was, for example, a ban on the books and newspapers coming from Serbia. [46] Kállay was intent on shaping Bosnia-Herzegovina without allowing any influence from across the border. The isolation of the Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina from their

co-nationals in Serbia and Montenegro was central to the Austro-Hungarian policy of absorbing Bosnia into the Dual Monarchy.

To ensure Bosnia-Herzegovina’s separation from Serbia and Montenegro, Kállay resorted to constructing a unified “Bosnian nation”. By imposing the concept of an alleged “Bosnian nation” through a series of administrative measures Kállay strove to suppress the existing and well-developed modern national identities, Serbian in the first place. Not surprisingly, Orthodox Serbs, who made up nearly a half of Bosnia’s population, deeply resented such denationalizing measures.

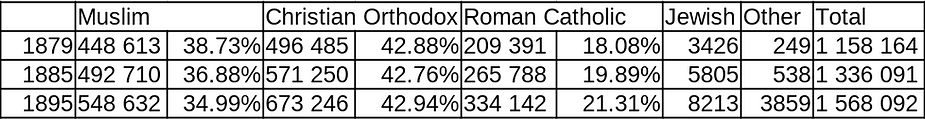

Table 1 Population of Bosnia-Herzegovina [47]

However, these attempts eventually failed. In 1896, representatives of the Christian Orthodox Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina sent a memorandum with their grievances to the Emperor Franz Joseph I. They complained about the violation of their “ecclesiastical and national” autonomy: non-Serb government agents attended their meetings, interfered in their decisions, removed all religious and historical symbols of the Serbs, and often replaced arbitrarily Serb priests and other legitimate religious representatives in contravention of the Serbs’ ecclesiastical and national autonomy. The use of Cyrillic alphabet, an important symbol of Serbian identity, was being suppressed and Latin alphabet imposed instead – this was part of the construction of a Bosnian nation. [48]

The Dual Monarchy dealt harshly with the leaders of the Serb national movement. The most common oppressive measure used against prominent Serbs was imprisonment. It was meant as a warning: they were usually released from prison after a short period of time. Another tactics was to tarnish the reputation of the imprisoned by spreading rumours of their collaboration with the occupation authorities among the Serbian population. [49] All signatories of the memorandum to Franz Joseph I were subjected to various forms of harassment and tacit discrimination.

While clamping down on the Serb national movement, Kállay also sought to separate Muslim Slavs, who largely had no national identity, from Christian Orthodox Serbs and Roman Catholic Croats. The Muslims were supposed to counterbalance the growing “Serbian nationalism”, while the preservation of their privileged feudal status over Christian Serb serfs served to keep the two communities divided. Kállay never forgot the Serbo-Muslim rebellions against Austro-Hungarian rule (1878 and 1882) and he was intent on preventing cooperation between Christian Orthodox Serbs and Muslim Slavs of Bosnia-Herzegovina. In his pivotal study The History of the Serbian people written during his days as consul-general in Belgrade Kállay stated that a large number of Muslim bey families were of Serbian origin and that they had converted to Islam in order to preserve their status and property. [50] He apparently was weary of the connections between the Muslim Slav and Serb population arising from their common origin.

The Muslim Slavs seemed perfect for Kállay’s nation-construction project. Most of the local feudal elite came from the ranks of local Muslim Slavs, whereas Serbs worked their land as dependent peasants. Kállay never initiated the much-needed agrarian reform because he wanted to protect the interests of Muslim landowners. A quarter of Muslim Slavs lived in urban environments and constituted the core of the artisanal class. Therefore, Muslim Slavs were the socially dominant community and seemed best suited to support the idea of a Bosnian nation as opposed to Serb and Croat nationalisms. [51] At the cultural-ideological level, Kállay wanted to forge a new identity for Bosnian Muslims by trying to create a link between pre-Ottoman traditions of the medieval Bosnian state, particularly those associated with the extinct Bogumil church, and the present-day bey class, cutting out entirely Islamic tradition. [52] Yet, many Muslims left Bosnia-Herzegovina to settle in the Ottoman-held lands of Turkey-in-Europe. Between 1878 and 1883, some 8,000 Muslims left Bosnia. [53] Furthermore, Austria-Hungary colonized Habsburgtreu population – Germans, Czechs, Croats, Poles – in their place. [54]

Table 2 Population increase in percentage [55]

The Roman Catholic population was better treated than the Christian Orthodox Serbs and Muslim Slavs, which created antagonisms that served well the purposes of the Dual Monarchy’s “divide and rule” policy. The Roman Catholics grew in number during Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In 1878, there were 209,391 Roman Catholics and their number reached 334,142 in 1895; in Sarajevo, the rise was striking: from 800 to 11,000 Roman Catholics. [56] Local Catholic priests, particularly Franciscan, were replaced with those loyal to the Dual Monarchy, mostly Jesuit. The latter were one of the important factors

in the Germanization of Bosnia-Herzegovina. [57] The Jesuits’ propaganda activity was not focused on the Roman Catholics alone. [58] The Bishop of Sarajevo, Josif Štadler, came into conflict with the Franciscans because, he claimed, they showed signs of religious tolerance and were inactive in terms of propaganda. [59]

Kállay spared no effort to impose the concept of the Bosnian nation but to no avail. The creation of a Bosnian flag and coat of arms, the publishing of newspapers and language reforms did not have the desired effect. In the late nineteenth century, genuine national movements were on the rise and precluded the success of his “Bosnian nation” project. Kállay had to accept that his plan bore no fruit. Shortly before his death, he stated that religious affiliation equalled national identity, thus effectively dropping the concept of the Bosnian nation.

Austria-Hungary’s “civilizing mission” required a large administration to accomplish its goals. No more than a quarter of civil sevants were born in Bosnia-Herzegovina. [60] Foreigners, mostly Germans, Poles, Hungarians, Czechs and Slovaks filled the most important administrative positions. In 1904, 34.5% of civil servants came from Austria, 38.29% from Hungary and 26.48% were the natives of Bosnia-Herzegovina. [61] It was nearly impossible for the natives to reach higher echelons of administration. Demands for liberalization of the administration were, however, left unanswered. Kállay desired an apolitical population under the firm control of the bureaucracy. [62] As one of the foremost British historians noted, “one can point out that taxes increased fivefold under Austria’s administration and that the bureaucracy which had comprised only 120 men under the Turks rose to 9,533 in 1908. […] administration played off Croats against Serbs and encouraged Croats and Mohammedans to cooperate. If all this did not represent imperialism, it is difficult to know what it did represent.” [63]

The number of schools was in steady decline. According to the 1906 report on Bosnia-Herzegovina, there were 352 schools in 1904/5, of which 239 public schools, 103 confessional schools and 10 private schools. On average there was one public school for every 4,455 inhabitants. This compares poorly with the average of one public school for 2,264 inhabitants in Serbia at the time. [64] The situation in secondary education was similar, but the Dual Monarchy maintained that there were more than enough schools. [65] There were three gymnasiums in all of Bosnia-Herzegovina – in Sarajevo, Mostar and Tuzla – with a total of 1,024 students. [66] Between 1887 and 1918, 723 students graduated from the Sarajevo gymnasium. Out of this number, 102 were Muslim Slavs (14%), 220 were Orthodox Serbs (30%) and 310 were Roman Catholics (40%). [67] It should be noted that whereas the University of Cairo was founded in 1908, i.e. while Egypt was still under the “veiled protectorate” of Great Britain, Austria-Hungary never opened a university in Bosnia-Herzegovina. This no doubt had to do with the constant fear of liberal and progressive ideas that could be spread from universities.

In public schools, students learned only from the textbooks approved and published by the government of Bosnia-Herzegovina, while private and confessional schools used books of their own choice. Serbian schools, understandably, used textbooks from Serbia or local books that were not consistent with Austria-Hungary’s official policy. The Dual Monarchy reserved the right to ban certain Serbian books if the authorities found them inappropriate for Bosnia-Herzegovina. [68] Interestingly, even the content of Kállay’s own History of the Serbian people was deemed problematic and the book was banned informally. Kállay asked Lajos Thallóczy, a Hungarian historian, to write a history of Bosnia and school textbooks which would lend scholarly support to the construct of the “Bosnian nation” which had allegedly existed since the middle ages. [69] The foreigners settled in Bosnia-Herzegovina sent their children to private schools which catered to their requirements.

The most pressing problem was the need to carry out the agrarian reform, but that was not to happen. There was no serious attempt to emancipate the dependent peasantry (kmets), mostly Christian Orthodox Serbs. In the economic sphere, Bosnia-Herzegovina’s incorporation into the customs system of the Dual Monarchy meant that Vienna dominated the market and completely suppressed goods from other markets and the products of local artisans, ruining the local economy. [70]

Conclusion

The colonial nature of the British regime in Egypt is unquestionable in historiography. On the other hand, for all its distinctly colonial features, the rule of Austria-Hungary in Bosnia-Herzegovina, despite being colonial, is often perceived as a period of modernization. However, the two cases are strikingly similar: the two occupations coincide in time, the “administrators” had similar careers before arriving in Egypt and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and, most importantly, the arguments given to explain and justify both occupations were typical of the age of “New Imperialism”.

Both occupation regimes were provisional in character. There was no timeframe for the British to withdraw from Egypt. With the false promise of leaving Egypt once order had been restored and with no legal limits to its “rule”, Britain established a “veiled protectorate”. On the other hand, Austria-Hungary was given a mandate by European powers to occupy Bosnia-Herzegovina with the mission to “bring order” within thirty years.

Both Baring and Kállay directed the work of a large administrative apparatus and had to deal with national movements – that was their greatest challenge. Political freedoms in the occupied territories were almost non-existent and neither occupation regime tackled the agrarian question. Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina was consistent with the desire of the Habsburg politicians to conquer foreign lands with their civilization and economy. Contemporaries saw similarities between the status of Bosnia-Herzegovina and that of Cyprus and Tunisia. [71]

As for differences, Egypt had its local dynasty and the khedive became the focal point of the national movement. Unlike Egypt and Britain, Bosnia-Herzegovina shared a common border with the Dual Monarchy before the occupation, but it was also conterminous with Serbia and Montenegro, which were central to the national liberation movement of the Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The most important features of the British regime in Egypt and the Austro-Hungarian regime in Bosnia-Herzegovina were the suppression of national movements, and complete control of political life and education. The Dual Monarchy sought primarily to suppress the Serb national movement by imposing the construct of a “Bosnian nation.” Even when the experiment with the “Bosnian nation” failed and true national movements grew in strength, the Dual Monarchy continued to control and limit access to education in Bosnia-Herzegovina. All hope that the oppressive foreign rule would be relaxed after Kállay’s death

in 1903 soon died out and the Dual Monarchy continued to treat the occupied province in a manner typical of the age of “New Imperialism”.

UDC 327.2(410:620)”1878/1903”

327.2(436:497.15)”1878/1903”

References:

[1] M. Ković, “’Civilizatorska’ misija Austorugarske na Balkanu – pogled iz Beograda”, Istraživanja 22 (2011), 365–367.

[2] H. Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1973), 185.

[3] Ibid. 186.

[4] K. Fahmy, “The Era of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, 1805–1848”, in The Cambridge History of

Egypt, vol. 2: Modern Egypt From 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, ed. M. W. Daly

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 139–140.

[5] Ibid. 174.

[6] F. R. Hunter, “Egypt under successors of Muhammad ‘Ali”, in The Cambridge History of

Egypt, vol. 2, 181.

[7] A. Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot, A History of Egypt. From the Arab Conquest to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 79.

[8] Hunter, “Egypt under successors of Muhammad ‘Ali”, 196.

[9] Ibid. 197.

[10] R. Owen, Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 114–117.

[11] According to the 1882 census, Egypt had a population of 6,806,381; there were 90,886

foreigners, of whom 6,118 were British. It is believed that the native population was larger

by at least 100,000 persons, since Egyptians were fearful about conscription, cf. L. Mak,The

British in Egypt: Community, Crime and Crisis 1822–1922 (London; New York: I. B. Tauris,

2012), 15–17.

[12] A. Goldschmidt, “al-Afghani, Jamal al-Din”, in Historical Dictionary of Egypt, ed. A. Goldschmidt, Jr. (London: Boulder, 2000), 32.

[13] Editors of the newspaper Young Egypt were among the deported, cf. D. M. Reid, “The

Urabi Revolution and the British Conquest 1879–1882”, in The Cambridge History of Egypt,

vol. 2, 222–223.

[14] Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot, A History of Egypt, 85.

[15] Ibid. 87.

[16] Memorandum austrougarske vlade britanskoj vladi (21 April/3 May) 1878, published in

Balkanski ugovorni odnosi (1876–1996), vol. I:1876–1918, ed. M. Stojković (Belgrade: Službeni

list SRJ, 1998), 92–99

[17] R. Okey,Taming Balkan Nationalism. The Habsburg “Civilizing Mission” in Bosnia 1878–

1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 1.

[18] T. Kraljačić, Kalajev režim u Bosni i Hercegovini (1882–1903) (Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša,

1987), 22.

[19] Okey, Taming Balkan Nationalism, 2.

[20] D. T. Bataković, “Prelude to Sarajevo: the Serbian question in Bosnia and Herzegovina

1878–1914”, Balcanica XXVII (1996), 119.

[21] R. Jeremić, “Oružani otpor protiv Austro-Ugarske”, in Napor Bosne i Hercegovine za oslobodjenjem i ujedinjenjem, ed. P. Slijepčević (Sarajevo: Štamparija Prosveta 1929), 67.

[22] Croatian general Josip Filipović was in command of the occupation army. He insisted on

the formation of a local police force that would include local population loyal to the Dual

Monarchy, mostly Roman Catholics, cf. V. Skarić, O. Nuri-Hadžić and N. Stojanović, Bosna

i Hercegovina pod Austro-Ugarskom upravom (Belgrade: Geca Kon, 1938), 12.

[23] Jeremić, “Oružani otpor”, 69.

[24] S. Szabó, “Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Administration under Habsburg Rule, 1878–1918”, The

South Slav Journal 31/ 1-2 (2012), 55–57.

[25] Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism, 210–212.

[26] Ibid. 213.

[27] Ibid. 214.

[28] Earl of Cromer, “The Government of Subject Races”, Political and Literary Essays 1908–1913 (London: Macmillan & Co., 1913), 3–53.

[29] Okey, Taming Balkan Nationalism, 57. For more on Kállay’s ideas see B. Kállay, Ugarska na granici istoka i zapada (Sarajevo: Zemaljska štamparija, 1905).

[30] A. Sked, The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire1815–1918 (London: Longman, 1999), 245.

[31] Owen, Lord Cromer, 56.

[32] R. Okey, “A Trio of Hungarian Balkanists: Béni Kállay, István Burián and Lajos Thallóczy

in the Age of High Nationalism”, The Slavonic and East European Review 80/2 (April 2002), 235.

[33] Kraljačić, Kalajev režim, 48–49.

[34] Dnevnik Benjamina Kalaja 1868–1875, ed. A. Radenić (Belgrade; Novi Sad: Istorijski institut, 1976), 116.

[35] Kraljačić, Kalajev režim, 55.

[36] M. W. Daley, “The British occupation 1882–1922”, in The Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. 2, 240.

[37] A. Milner, England in Egypt (London: E. Arnold, 1902), 172.

[38] Daley, “The British Occupation 1882–1922”, 241.

[39] Owen, Lord Cromer, 241.

[40] Mak, British in Egypt, 19.

[41] Earl of Cromer, Abbas II (London: Macmillan, 1915), 4.

[42] R. L. Tignor, Egypt – A Short History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 236–237.

[43] Kraljačić, Kalajev režim, 89.

[44] Jeremić, “Oružani otpor”, 77.

[45] Ibid. 78.

[46] Kraljačić, Kalajev režim, 115–116.

[47] Dj. Pejanović, Stanovništvo, školstvo i pismenost u krajevima bivše Bosne i Hercegovine (Sarajevo: Prosveta, 1939), 3.

[48] D. T. Bataković, The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina. History and Politics( Paris: Dialogue,

1996), 66.

[49] Maksimović, “Crkvene borbe i pokreti”, 83.

[50] V. Kalaj, Istorija srpskog naroda (Belgrade: Petar Ćurčić, 1882), 148.

[51] Okey, Taming Balkan Nationalism, 92

[52] Ibid. 60.

[53] Maksimović, “Crkvene borbe i pokreti”, 93; Izveštaj o upravi Bosne i Hercegovine 1906, Zagreb 1906, 9.

[54] Maksimović, “Crkvene borbe i pokreti”, 91.

[55] J. Cvijić, Aneksija Bosne i Hercegovine i srpski problem (Belgrade: Državna štamparija Kraljevine Srbije, 1908), 30.

[56] Maksimović, “Crkvene borbe i pokreti”, 97.

[57] Ibid. 99–100.

[58] Skarić, Nuri-Hadžić, Stojanović, Bosna i Hercegovina pod Austro-ugarskom upravom, 35.

[59] V. Ćorović, Odnosi izmedju Srbije i Austro-Ugarske u XX veku (Belgrade: Državna štamparija Kraljevine Jugoslavije, 1936), 163.

[60] Kraljačić, Kalajev režim, 439.

[61] Ćorović, Odnosi izmedju Srbije i Austro-Ugarske u XX veku, 162.

[62] R. J. Donia, Islam under the Double Eagle: The Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1878–1914 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), 14.

[63] A. Sked, The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire, 245.

[64] Izveštaj o upravi Bosne i Hercegovine 1906, 137.

[65] Ibid. 138.

[66] Ibid. 180.

[67] S. M. Džaja, Bosna i Hercegovina u austrougarskom razdoblju (1878–1918) (Mostar-Zagreb: Ziral, 2002), 141–142.

[68] Izveštaj o upravi Bosne i Hercegovine 1906, 140.

[69] I. Ress, “Lajos Thallóczys Begegnungen mit der Geschichte von Bosnien-Herzegowina”,

in Lajos Thallóczy, der Historiker und Politiker, eds. Dž. Juzbašić and I. Ress (Sarajevo: Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste von Bosnien-Herzegowina; Budapest: Ungarische

Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2010), 61.

[70] Dž. Juzbašić, Politika i privreda u Bosni i Hercegovini pod austrougraskom upravom (Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 2002), 142.

[71] M. Ković, “Nacionalizam”, in Srbi 1903–1914: Istorija ideja, ed. M. Ković (Belgrade: Clio,

2015), 213–214.

Bibliography and sources

Balkanski ugovorni odnosi (1876–1996). Vol. I:1876–1918, ed. M. Stojković. Belgrade: Službeni

list SRJ, 1998.

Dnevnik Benjamina Kalaja 1868–1875, ed. A. Radenić. Belgrade; Novi Sad: Istorijski institut,

1976.

Cromer, Evelyn Barig, Earl of.Abbas II. London: Macmillan, 1915.

—Political and Literary Essays 1908–1913. London: Macmillan & Co., 1913.

Izveštaj o upravi Bosne i Hercegovine 1906.Zagreb 1906.

Kalaj, V.Istorija srpskog naroda.Belgrade: Petar Ćurčić, 1882.

— Kállay, B.Ugarska na granici istoka i zapada.Sarajevo: Zemaljska štamparija, 1905.

Milner, A.England in Egypt.London: E. Arnold, 1902.

Arendt, H.The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1973.

Bataković, D. T. “Prelude to Sarajevo: the Serbian question in Bosnia and Herzegovina

1878–1914”.BalcanicaXXVII (1996), 117–155.

—The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina. History and Politics.Paris: Dialogue, 1996.

Ćorović, V.Odnosi između Srbije i Austro-Ugarske u XX veku.Belgrade: Državna štamparija

Kraljevine Jugoslavije, 1936.

Cvijić, J.Aneksija Bosne i Hercegovine i srpski problem.Belgrade: Državna štamparija Kralje-

vine Srbije, 1908.

Daley, M. W. “The British occupation 1882–1922”. InThe Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. 2:

Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, ed. M. W. Daly, 239–251.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Donia, R. J.Islam under the Double Eagle: The Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1878–1914.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Džaja, S. M.Bosna i Hercegovina u austrougarskom razdoblju (1878–1918).Mostar; Zagreb:

Ziral, 2002.

Fahmy, K. “The Era of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, 1805–1848”. InThe Cambridge History of

Egypt, vol. 2:Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, ed. M. W. Daly,

139–179. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Grdjić, Š. “Prosvetne borbe”. InNapor Bosne i Hercegovine za oslobodjenjem i ujedinjenjem, ed.

P. Slijepčević, 107–166. Sarajevo: Prosveta, 1929.

Historical Dictionary of Egypt,ed. A. Goldschmidt, Jr. London: Boulder, 2000.

Hunter, F. R. “Egypt under successors of Muhammad ‘Ali”. InThe Cambridge History of Egypt,

vol. 2:Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, ed. M. W. Daly, 180–

197. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Jeremić, R. “Oružani otpor protiv Austro-Ugarske”. InNapor Bosne i Hercegovine za oslobo-

djenjem i ujedinjenjem, ed. P. Slijepčević, 66–78. Sarajevo: Prosveta, 1929.

Juzbašić, Dž.Politika i privreda u Bosni i Hercegovini pod austrougraskom upravom. Sarajevo:

Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 2002.

Ković, M. “’Civilizatorska’ misija Austorugarske na Balkanu – pogled iz Beograda”.Istraživ-

anja22 (2011), 365–379.

— “Nacionalizam”. InSrbi 1903–1914L Istorija ideja, ed. M. Ković, 202–269. Belgrade: Clio,

2015.

Kraljačić, T.Kalajev režim u Bosni i Hercegovini (1882–1903). Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša, 1987.

Lutfi Al-Sayyid Marsot, A.A History of Egypt. From the Arab Conquest to the Present. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Mak, L.The British in Egypt: Community, Crime and Crisis1822–1922. London; New York: I.

B. Tauris, 2012.

Maksimović, M. “Crkvene borbe i pokreti”. InNapor Bosne i Hercegovine za oslobodjenjem i

ujedinjenjem, ed. P. Slijepčević, 79–106. Sarajevo: Prosveta, 1929.

Okey, R. “A Trio of Hungarian Balkanists: Béni Kállay, István Burián and Lajos Thallóczy in

the Age of High Nationalism”.The Slavonic and East European Review80/2 (April 2002),

234–266.

—Taming Balkan Nationalism. The Habsburg “Civilizing Mission” in Bosnia 1878–1914.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Owen, R.Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul.Oxford: Oxford Univer-

sity Press, 2004.

—The Middle East in the World Economy 1800–1914.London: I. B. Tauris 2009.

Pejanović, Dj.Stanovništvo, školstvo i pismenost u krajevima bivše Bosne i Hercegovine.Sarajevo: Prosveta, 1939.

Reid, D. M. “The Urabi Revolution and the British Conquest 1879–1882.”InThe Cambridge

History of Egypt, vol. 2:Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, ed.

M. W. Daly, 217–238. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Ress, I. “Lajos Thallóczys Begegnungen mit der Geschichte von Bosnien-Herzegowina”. In

Lajos Thallóczy, der Historiker und Politiker, eds. Dž. Juzbašić and I. Ress, 53–80. Sara-

jevo: Akademie der Wissenschaften und Künste von Bosnien-Herzegowina; Budapest:

Ungarische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2010.

Skarić, V., P. Nuri-Hadžić and N. Stojanović.Bosna i Hercegovina pod austro-ugarskom upra-

vom. Belgrade: Geca Kon, 1938.

Sked, A.The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire1815–1918. London: Longman, 1999.

Szabó S. “Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Administration under Habsburg Rule, 1878–1918”.The

South Slav Journal31/1-2 (2012), 52–78.

Tignor, R. L.Egypt – A Short History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.